Ripping Up History

The Middle Fork Watershed Restoration and Road Closure Project Environmental Assessment (EA) is now available for public review.

The Legal Notice starting the 30-day public comment period appeared in the Eugene Register-Guard this morning, Nov. 29. See attached letter [here] for details.

Musings From Long Ago

by Bear Bait

I worked with a yarder engineer in the late 1960’s who was raised in the Dexter area. He related a story about he and his older brother and their summer job.

He was maybe 10 or 11, and his older brother was 14 or so. The date was pre-WWI. They would take a team with barrels and salt, and their camping outfit, and drive up the Willamette River on the old military wagon road that skirts the south side of Diamond Peak. Way up the Willamette, which he said had lots of horse graze and great camping spots. Their job was to catch fish and salt them. Fill the wagon. And then drive home with a wagon full of salted fish.

He said salmon trout and salmon, mostly. I was not smart enough to ask how they caught them. He said they picked apples all the way home, from trees along the wagon road.

My Uncle Carl, now 82, attended the Boy Scout camp at Camp Lucky Boy, which is now submerged under the Lookout Point Reservoir. He said his favorite activity was fly-fishing for cutthroat trout, which were mostly about a foot long to maybe 16″.

In those days, before dams, the cutthroat migrated seasonally in river. Down river in the spring to feed in the mainstem, and up river in the fall, and then up small tributaries to spawn from January through April. I can remember walking down to the fish ladder on the Mary’s River at Corvallis, in spring, to see the big cutthroat going up the fish ladder to spawn in the upper reaches of the Mary’s River.

The dam was there at the mouth to make the log pond for the Corvallis Lumber Company, a division of Willamette Ind. They had a rail dump, and then later trucks only. The rail came in from Beaver Creek and out the east face of the Coast Range south of Corvallis.

One day early in my log buying career, I was looking at some Starker logs due south of the Mary’s Peak turnoff, across the highway, and the logger’s landing was set up where the last rigged tree for Willamette still stood, hayrack and squirrel and the works. Loading trucks under a rigged tree. They left the tree rigged when the job was done. Probably about the time the mill closed.

I also was looking for a BLM sale on Prairie Mountain one afternoon, late, in the rainy season, and I came around a corner in the road, and there was a rigged tree with a hayrack and a loading bitch over one side of the landing, and the yarder on the other, and rain drops were still making steam hitting the still warm exhausts of the two donkeys. But nobody there. I had missed the crew, I suppose because they were on the Hull-Oakes private road.

I think I was looking for some Pope and Talbot wood for sale. Or BLM… But that was the last full rigged tree and loading pot I ever saw in the woods. I worked on lots of rigged trees in my life, but always we had a shovel loader with tongs… until grapples… which lasted about 15 years, and then all hydraulic loaders after that. Man, some of the grapple runners could put those grapples anywhere. And pitch a cull over the side, and it looked like the shovel actually was holding its nose like something smelled bad…

Musings from long ago… bear bait

Forestry education Restoring cultural landscapes Saving Forests

by admin

1 comment

Machu Picchu of the Umpqua

by Mike Dubrasich, Exec Dir W.I.S.E.

Last summer intrepid researchers rediscovered an ancient Indian village perched on a recondite ridgetop in Oregon’s Cascade Mountains. Preliminary findings indicate that the site has been occupied for at least 3,000 years, or five times longer than the Incan sanctuary of Machu Picchu in Peru [here].

Now known as Huckleberry Lake, the ancient village was likely a summer residence for tribes from both the Umpqua and Rogue watersheds, including Molallan, Takelman, and Latgawan people, in recent precontact times (prior to ~1800).

Huckleberry Lake in 2010. Click for larger image. Photo courtesy Bob Zybach, Oregon Websites and Watersheds Project, Inc.

Following leads from Chuck Jackson, elder of the Cow Creek Band of the Umpqua Tribe, landscape historians Dr. Bob Zybach and Nana Lapham located abundant evidence of ancient human use along the Rogue-Umpqua Divide in the vicinity of Huckleberry Lake. That evidence includes mortar and pestle rocks, obsidian debitage, food and fiber plants, and an ancient trail system, all consistent with oral histories of the Cow Creeks.

The Rogue-Umpqua Divide is a southwest tending spur of the north/south tending High Cascades that extends ~20 miles west of the Cascade Crest at elevations above 5,000 feet. Huckleberry Lake is on the westernmost point of the Rogue-Umpqua Divide, less than a day’s walk from known winter village sites near Tiller, OR.

Numerous springs that arise seemingly from the ridgetop are fed by lava tubes originating far to the east. They water small lakes perched above steep canyons that fall away to the north and south. Athough the vegetation today consists of dense true firs, remnant huckleberry fields (Vaccinium membranaceum) are evidence of a larger huckleberry complex that once carpeted the entire Divide [here].

Human tending with frequent anthropogenic fire must have been the principal factor that maintained the huckleberry brushfields, by excluding tree invasions. In the absence of such tending over the last 100 years or so, tree invasion has been extensive.

Dr Zybach stated:

There is very little history or other information available about the people who lived in the study area 200 years ago; however, much can be inferred from what is known of neighboring Tribes of that time, the presence and extent of current and historical vegetation patterns (particularly those of food and fiber plants), archaeological research, and known precontact travel and trade routes. Because people at that time did not have horses and because the South Umpqua headwaters are not navigable by canoe, travel was done by foot, along well-established ridgeline and streamside trail systems. Primary destinations would have been local village sites, seasonal campgrounds, peaks, waterfalls, the mouths of streams, and various crop locations, such as huckleberries, camas, and acorns.

Trail networks indicate where people went at certain times of the year, where they camped, and where they came from (or went to). Trails connect principal seasonal campgrounds, based on food harvesting and processing schedules, fishing and hunting opportunities, and trade. Freshwater springs at higher elevations were a critical element, such as Neil Spring near Huckleberry Lake.

Location and carbon dating of ancient home sites at Huckleberry Lake has yet to be done, but camas ovens in the area (with charcoal that has been carbon dated) indicate “intense and continuous [occupation] between 3,000 and 300 years ago” by Native Americans [here].

The research efforts are part of the South Umpqua Headwaters Precontact Reference Conditions Study, sponsored by Douglas County and supported by the Umpqua National Forest and the Cow Creek Band of the Umpqua Tribe.

Forestry education Restoring cultural landscapes Saving Forests

by admin

leave a comment

Four New Colloquia Posts

After a long hiatus (been working on a paper) we are pleased to announce the posting of four new works in our Colloquia:

Nataraja: India’s Cycle of Fire by Stephen J. Pyne may be found [here]. Dr. Pyne’s essay on the history of fire on the Indian subcontinent is a chapter from World Fire: The Culture of Fire on Earth (Pyne S.J., 1997, Univ of WA Press). He graciously sent it to W.I.S.E. as a companion piece to Roger Underwood’s Baden-Powell and Australian Bushfire Policy [Part 1 here, Part 2 here]. An extracted gem of a quote:

India’s biota, like Shiva, dances to their peculiar rhythm while fire turns the timeless wheel of the world. Perhaps nowhere else have the natural and the cultural parameters of fire converged so closely and so clearly. Human society and Indian biota resemble one other with uncanny fidelity. They share common origins, display a similar syncretism, organize themselves along related principles. Such has been their interaction over millennia that the geography of one reveals the geography of the other. The mosaic of peoples is interdependent with the mosaic of landscapes, not only as a reflection of those lands but as an active shaper of them (emphasis added). Indian geography is thus an expression of Indian history, but that history has a distinctive character, of which the nataraja is synecdoche, a timeless cycle that begins and ends with fire.

Stand Reconstruction and 200 Years of Forest Development on Selected Sites in the Upper South Umpqua Watershed, W.I.S.E. White Paper 2010-5 by yours truly (and the cause of the recent hiatus), examines the forest development pathways over the last 200 years in an Oregon Cascades watershed:

Several lines of evidence suggest that the prairies, savannas, and open forests have been persistent vegetation types in the Upper South Umpqua Watershed for the last few thousand years, at least. Precontact forest development pathways were mediated by frequent, purposeful, anthropogenic fires deliberately set by skilled practitioners, informed by long cultural experience and traditional ecological knowledge in order to achieve specific land management objectives. At a landscape scale the result was maintenance of an (ancient) anthropogenic mosaic of agro-ecological patches. In the absence, over the last 150 years, of purposeful anthropogenic fires, the anthropogenic mosaic has been invaded and obscured by (principally) Douglas-fir. As a result, the Upper South Umpqua Watershed is now at risk from a-historical, catastrophic stand-replacing fires.

In Pre-Columbian agricultural landscapes, ecosystem engineers, and self-organized patchiness in Amazonia by Doyle McKey, Stephen Rostain, Jose Iriarte, Bruno Glaser, Jago Jonathan Birk, Irene Holst, and Delphine Renard, the authors examine the manner in which arthropods and other critters have maintained nutrient-rich soils long after the pre-Columbian human residents created said soils:

Combining archeology, archeobotany, paleoecology, soil science, ecology, and aerial imagery, we show that pre-Columbian farmers of the Guianas coast constructed large raised-field complexes, growing on them crops including maize, manioc, and squash. Farmers created physical and biogeochemical heterogeneity in flat, marshy environments by constructing raised fields. When these fields were later abandoned, the mosaic of well-drained islands in the flooded matrix set in motion self-organizing processes driven by ecosystem engineers (ants, termites, earthworms, and woody plants) that occur preferentially on abandoned raised fields.

In The Columbian Encounter and the Little Ice Age: Abrupt Land Use Change, Fire, and Greenhouse Forcing by Robert A. Dull, Richard J. Nevle, William I. Woods, Dennis K. Bird, Shiri Avnery, and William M. Denevan, the (accomplished and distinguished) authors posit that Old World disease epidemics in the 1500’s eliminated anthropogenic fire along with the human population of Amazonia. The decline in human-driven carbon cycling was at a continental scale, and the reduction in emitted CO2 may have induced the Little Ice Age:

Pre-Columbian farmers of the Neotropical lowlands numbered an estimated 25 million by 1492, with at least 80 percent living within forest biomes. It is now well established that significant areas of Neotropical forests were cleared and burned to facilitate agricultural activities before the arrival of Europeans. Paleoecological and archaeological evidence shows that demographic pressure on forest resources—facilitated by anthropogenic burning—increased steadily throughout the Late Holocene, peaking when Europeans arrived in the late fifteenth century. The introduction of Old World diseases led to recurrent epidemics and resulted in an unprecedented population crash throughout the Neotropics. The rapid demographic collapse was mostly complete by 1650, by which time it is estimated that about 95 percent of all indigenous inhabitants of the region had perished. We review fire history records from throughout the Neotropical lowlands and report new high-resolution charcoal records and demographic estimates that together support the idea that the Neotropical lowlands went from being a net source of CO2 to the atmosphere before Columbus to a net carbon sink for several centuries following the Columbian encounter. We argue that the regrowth of Neotropical forests following the Columbian encounter led to terrestrial biospheric carbon sequestration on the order of 2 to 5 Pg C, thereby contributing to the well-documented decrease in atmospheric CO2 recorded in Antarctic ice cores from about 1500 through 1750, a trend previously attributed exclusively to decreases in solar irradiance and an increase in global volcanic activity. We conclude that the post-Columbian carbon sequestration event was a significant forcing mechanism.

It’s a hypothesis that is very difficult to test, but one that recognizes the historical impact of human beings on the environment. That theme permeates all four new Colloquia postings.

Our protocol with Colloquia postings is that comments there must be scholarly, commensurate with the scientific efforts of the authors. Less than scholarly comments on any of the postings are welcome, but should be placed here (see the leave a comment aplet below).

We endeavor to post the best, cutting-edge research papers, and all of these meet our stringent criteria. They are not too technical for the lay audience, though. I hope you enjoy them.

Politics and politicians Restoring cultural landscapes Saving Forests The 2010 Fire Season

by admin

1 comment

Another Forest Tragedy

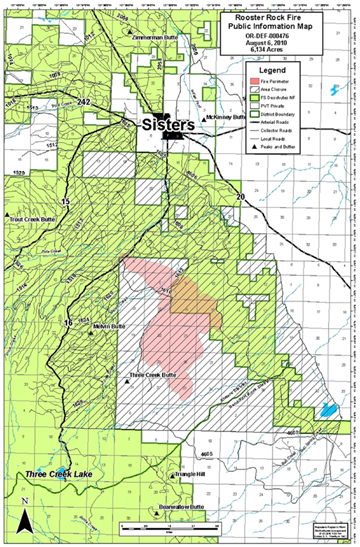

The Rooster Rock Fire [here] near Sisters, Oregon is now 6,124 acres and 65% contained. It is unlikely to grow any larger because winds have died down and the CO2’s (Central Oregon Type 2 Incident Management Team, Mark Rapp I.C.) in cooperation with the Oregon Dept. of Forestry have done their usual excellent job of controlling the fire.

The fire began from unknown causes on US Forest Service (Deschutes NF) land on August 2nd. It quickly spread east and south to private lands. Approximately three-quarters of the area burned by the Rooster Rock Fire is private land.

Rooster Rock Fire Map, 08/06/2010, courtesy Central Oregon IMT. Click for larger image.

The fire was about 5 miles south of Sisters. A few homes were evacuated, but the evacuations have now been lifted. An estimated 50 homes were threatened, but no homes burned.

The Rooster Rock Fire was the 13th large fire in the northern Deschutes NF in the last 8 years. Over 160,000 acres, primarily in the the Metolius River watershed, have been incinerated. The scar of burned old-growth now extends from Warm Springs to the north to the Three Sisters Wilderness to the south, from the Cascade Crest to private lands to the east. The following Burns make up this destroyed forest landscape (this list is missing a few smaller ones):

Cache Mountain Fire (2002) - 3,894 acs

Eyerly Complex Fires (2002) - 23,573 acs

B&B Complex Fires (2003) - 90,769 acs

Link Fire (2003) - 3,574 acs

Black Crater Fire (2006) - 9,400 acs

Puzzle Fire (2006) - 6,150 acs

Lake George Fire (2006) - 5,740 acs

GW Fire (2007) - 7,500 acs

Dry Creek Fire (2008) - 110 acs

Summit Springs Complex Fires (2008) - 1,973 acs

Wizard Fire (2008) - 1,840 acs

Black Butte II Fire (2009) - 578 acs

Rooster Rock Fire (2010) - 6,124 acs

Total - 161,225 acres in eight fire seasons

Squandering the Wisdom

Native Americans maintained American forests before the Europeans arrived and knew what they were doing.

Words and photos by Steven H. Rich, Range Magazine, Summer 2010 [here]

Selected excerpts:

The Danish forest ecologist sighed explosively, then spoke: “Your government’s wildfire and forest policy is a foolish and ignorant insult to the poor, and an insult to nature.” His voice was shaking, his tone illustrating the fact that grownups sigh when weeping seems out of place.

“Do you know the estimates of unused logging residues and dead wood rotting in your country are equivalent to 32 billion barrels of oil [more than four year’s supply for the whole nation]? When ecologists project a yearly total of the ecologically available logging waste [branches and tops] generated on private lands in the United States to all your forests, it makes 1.36 billion barrels [a good start on the 20 million barrels a day we use].

Do you know what that waste does to the price of fuel in poor countries? Every year you let another two- to six-million acres burn up! You do nothing effective to stop it and you do nothing with it!” …

The American public is not told that three times the CO emitted during any severe fire event continues to reach the atmosphere as the dead wood continues to degas and decompose. The environmentalists’ pro-wildfire/no-logging policy is a gigantic CO and other biogas factory, stacking up more and more “production units” in the form of billions of “sacred” dead trees which — due to lawsuits — no one is allowed to harvest. Frivolous fund-raising lawsuits that prevent sound use of forest biomass alternatives could end up as the single greatest cause of American fossil carbon releases, while hugely accelerating detructive fire emissions. …

The policy — letting disease-ridden too-dense forest structures continue and allowing fuel loads to build — kills forests. On average, they burn at least twice by the time the trees of the first fire decompose. The fire that burns the wind-fallen and/or rot-fallen fire-killed trees is vastly more destructive than the first.

In close contact with forest soils, the 1,700-degree Fahrenheit heat of 200 tons per acre of downed logs deeply sterilizes the forest floor. These intense blazes can last for many hours. Few biological potentials survive, nor does the wildlife that depends on these habitats.

Researchers Matthew Hurteau and Malcolm North modeled six prescriptions for mixed-conifer forest structure to study their potential for carbon sequestration. They came up with basically the same answers that Dr. Wallace Covington at Northern Arizona University reached in his work: Do it the way the Native Americans did.

Allowing a tangled mass of stunted trees to grow does sequester (take out of the atmosphere) lots of carbon — until it catches fire. When fire is added to the model, it becomes clear that a forest of widely spaced big trees is much safer from fire and sequesters more carbon for much longer. …

The ecological, social and economic benefits vastly favor restoring the Native American forest-structure maintenance system. Every year, the stream flows will increase and stabilize, wildlife will increase and soils will grow richer. This is a grazeable woodland, very productive of biodiversity and progressively healthier. These are the landscapes from which dozens of Arizona trout streams once flowed down to broad, beautiful, lower-slope grasslands, which are now choked with alien Utah junipers and chaparral shrubs. …

Who would object to restoring paradise while aiding the cause of energy independence? Who objects to restoring rural economies, relieving taxpayers of the burden of supporting the Forest Service (which used to make money), and greatly enhancing our national security both through an ecologically positive boost in tax revenues and a huge drop in oil imports? …\

Long ago, Native Americans knew that the trees and shrubs grew too thickly choking out everything else and then catching fire, doing huge damage. They worked very hard and used cool-season fire to thin tree and shrub stands, release grasses and flowers from domination, make meadows, attract game and increase useful plants and animals. They also did it to protect their families from being burned to death. They greatly admired large trees and used small ones. They increased nut crops by decreasing competition from other trees. Their management plan greatly increased nuts, berries, bulbs, corms, basketry and cordage materials, grass-seed production, game and water. It created farming opportunities. It was intelligent, superbly adapted, highly sophisticated, and it created beauty.

The environmental movement must abandon the false belief that the America the European explorers found was “pristine” in any way. Almost every American landscape was what ethnologists and ethno-biologists call an anthropogenic (human-created) landscape. Doctrinaire environmentalists are trying to recreate a world that never existed. To deny the Native Americans’ role in the beauty and abundance Europeans found is to perpetuate the 15th-19th century assumption that they had no role. Rural Americans must firmly resist any plans which use nature unsustainably and result in diminished potentials.

New forest-products technologies make smaller trees profitable in making beautiful homes. We can now spare many of the forest giants to make a safer, more beautiful, more productive forest using the research-proven model that Native Americans created.

Steven H. Rich lives in Salt Lake City, Utah. He is president of Rangeland Restoration Academy [here]

Federal forest policy Restoring cultural landscapes Saving Forests

by admin

3 comments

The Douglas County Forest Predicament

by Mike Dubrasich

Yesterday Douglas County Commissioner Joe Laurance delivered an excellent testimony to Congress. I amplify that testimony with the following of my own, which was not invited by Congress, nor delivered to them, but is instead posted here.

Douglas County extends from the crest of the Oregon Cascades to the Pacific Ocean and encompasses the entire watershed of the Umpqua River, over 5,000 square miles. As of the census of 2000, there were 100,399 people, 39,821 households, and 28,233 families residing in the county.

Douglas County is one of the premier timber-producing counties in the nation. Approximately 25-30% of the labor force is employed in the forest products industry. Agriculture, mainly field crops, orchards, and livestock (particularly sheep ranching,) is also important to the economy of the county.

In 2008 approximately 416 million board feet of timber were harvested in Douglas County, less than one third of the historical average. The reason for that is the USDA Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management administer more than 50% of the county’s land, and their combined timber harvest in 2008 was less than 50 million board feet, less than 5% of their historical harvest and less than 1% of the annual growth on those lands.

In economic terms, considering stumpage value, remanufacture value, and the multiplier effect, a million board foot of timber is worth a million dollars and/or ten family wage jobs.

The precipitous decline (from historical levels) in timber harvest from federal lands in Douglas County costs the county’s economy 10,000 jobs per year. That has been the case for nearly 20 years now, since inception of the Northwest Forest Plan, and Douglas County has suffered enormously as a consequence.

As of last October, 23,336 Douglas County residents received food stamps. That is roughly a quarter of the population. The number has risen since.

The federal (USFS, BLM) forestland in Douglas County continues to grow timber at a prodigious rate. Over a half billion board feet are added very year. In other words, less than 1% of the annual growth is harvested each year.

That accumulating biomass has another effect on the economy of Douglas County. It fuels catastrophic fires that damage the watersheds, wildlife, public health and safety, recreation, and all businesses.

Federal forest policy Forestry education Politics and politicians Restoring cultural landscapes Saving Forests The 2009 Fire Season

by admin

1 comment

Douglas Co. Commissioner Joe Laurance July 15 Testimony

Today the House Subcommittee on National Parks, Forests and Public Lands held an Oversight Hearing on “Locally Grown: Creating Rural Jobs with America’s Public Lands”. Among the testimonies [here] was that of Joseph Laurance, County Commissioner, Douglas County, Oregon.

Commissioner Laurance brought up many important points, not the least of which is that that our national forests today are unnaturally loaded with fuels. Over 110 million acres are in Fire Regime Condition Class 2 and 3, the most hazardous conditions.

The safest condition is FRCC 1, of which there are 60 to million acres. Commissioner Laurance noted that FRCC 1 closely approximates the natural, historic conditions “characteristic of the ‘anthropogenic’ forest in the year 1800, immediately prior to the European American presence.”

The following is the full text of his remarks, with complementary photographs:

Testimony of Joseph Laurance, County Commissioner, Douglas County, Oregon before the House Natural Resources Committee, Subcommittee on National Parks, Forests and Public Lands, July 15, 2010.

Distinguished members of the committee,

At a meeting of Oregon county commissioners last summer, I complained to my colleagues that while endless debate continued in congress about how federal forests should be managed, fires were ravaging federal timberlands in my county and throughout the western United States. The worldwide financial crisis that was draining the national treasury made re-authorization of “Secure Rural Schools” funding seem doubtful, threatening many of Oregon’s 36 counties with social and economic ruin. Bad news just kept coming with the word that unemployment in Douglas County had reached 16.4% and if unreported joblessness was considered, was probably greater than the 19% experienced here during the height of the “Great Depression”.

Talks were ongoing in Copenhagen about greenhouse gas emissions while the three fires in my county burned toward an eventual total of 20,000 acres, equal to the greenhouse gasses emitted by one million cars in a year’s time. My fellow commissioners suggested that I craft a solution to the problems you of this body are all too familiar with. The resultant resolution* has been carefully considered by commissioners from across the western United States who helped in its preparation. It has been unanimously adopted by the Association of Oregon Counties, Western Interstate Region of Counties, and the National Association of Counties (NACo) Public Lands Committee and is expected to be adopted by NACo at its annual national conference next week.

Twenty years and twenty days ago the Northern Spotted Owl was listed as threatened under the federal “Endangered Species Act”. It was then thought that loss of old growth habitat through logging was the culprit causing a declining population. In response, federal timber harvests were vastly curtailed. The Umpqua National Forest in my county saw an annual harvest of 397 million board feet in 1988 reduced to 4 million board feet in 2002. In the years since a policy of “benevolent neglect” of federal lands has seen Spotted Owl numbers continue to decline through habitat destruction caused by increasingly numerous and intense forest fires and through predation by the Barred Owl which favors this new “unmanaged” forest habitat. Federal policy, which had been multiple use of the forest with an emphasis on industrial harvest, sought a new strategy which has yet to be formulated in all these intervening years.

The resolution presented you provides that needed new strategy, not only for Oregon but for all of our nation’s federal forests from Appalachia to Alaska. Federal forest managers would now have a clearly defined desired forest condition that must be obtained within a specified time. If this becomes the “Intent of Congress”, the Forest Service and BLM would join with private industry to restore forest health and rural economies without drawing on the national treasury.

Federal forest policy Forestry education Restoring cultural landscapes Saving Forests

by admin

1 comment

The New Approach to Forest Stewardship

An encouraging Guest Editorial appeared in the Dead Tree Press yesterday, written by Tom Partin, president of the American Forest Resource Council:

Beyond the spotted owl: It’s time for a new approach in our federal forests

By Tom Partin, Guest Columnist, the Oregonian, July 08, 2010 [here]

The Oregonian’s recent article commemorating the 20th anniversary of the listing of the northern spotted owl on the endangered species list exposed the personal, largely hidden agendas of those who have advocated for the owl over the years. …

Now, after 20 years, it’s evident that slashing the harvest from our federal lands has not only made our forests into tinder boxes ready to ignite and burn the very habitat the owl needs, but has not kept the owl’s numbers from continuing to decline. By listening to the questionable wisdom of self-interested scientists whose livelihoods depend on grants to study the bird, we have come to a place where the owl is in far greater danger from fire and barred owls than from the boogeyman fall guy, logging. It’s time for a new approach.

Unfortunately, the new recovery plan for the spotted owl now under development by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is unlikely to be that new approach. …

When are Oregonians and our society going to say enough is enough? Our state is on the brink of bankruptcy, unemployment is topping 20 percent in rural Oregon, county payments that are handouts in lieu of cutting timber will expire in 2012, and our forests are ready to burn. What we are doing and have been doing isn’t working. … [more]

We concur with Mr. Partin’s observation that what we have been doing isn’t working. Specifically, the The Northwest Forest Plan has been a catastrophic failure. The NWFP had (has) four fundamental goals. It has failed spectacularly to meet any of them.

1. The NWFP has failed to protect northern spotted owls

By most estimations, the northern spotted owl population has fallen 40 to 60 percent since inception of the NWFP.

2. The NWFP has failed to protect spotted owl habitat

Since inception, millions of acres of spotted owl habitat have been catastrophically incinerated. Millions more acres are poised to burn.

3. The NWFP has failed to preserve habitat continuity throughout the range of the northern spotted owl

The dozens of huge and catastrophic forest fires have left giant gaps in the range. The Biscuit Burn alone is 50 miles long and 20 miles wide.

4. The NWFP has failed to protect the regional economy

Since inception of the NWFP, Oregon has experienced 15 long years of the worst economy in the U.S., with the highest rates of unemployment, bankruptcy, home foreclosure, and hunger of any state. These are not just statistics, but indicators of real human suffering. Over 40,000 workers lost their jobs, and the rural economy has been crippled ever since.

The plan to save the owls has not saved anything; not owls, not old-growth, not the economy. The cost for nothing? $100,000 per job per year x 40,000 jobs x 17 years = $68 billion. That’s what Northwesterners have paid, for nothing. And the bills continue to mount.

Mr. Partin calls for a “new approach.” We concur. More significantly, here at W.I.S.E. we have laid out the strategy for that new approach: restoration forestry.

Restoration forestry is active management to bring back historical cultural landscapes, historical forest development pathways, and traditional ecological stewardship to achieve historical resiliency to fire and insects and to preclude and prevent a-historical catastrophic fires that decimate and destroy myriad resource values [here].

Those values include:

1. Heritage and history

2. Ecological functions including old-growth development

3. Fire resiliency and the reduction of catastrophic fires

4. Watershed functions

5. Wildlife habitat protection and enhancement (including spotted owl habitat)

6. Public health and safety

7. Jobs and the economy

Restoration forestry begins with the study and elucidation of forest history. Mr. Partin is correct in his assessment that establishment forest science has failed to provide the research and understanding needed. Forest history has not been a key component of establishment forest science in univesities and forest research centers.

Despite that deplorable state of affairs, in enclaves outside the Establishment a handful of intrepid forest scientists have been exploring forest histories. Their principal findings have been that human influences over thousands of years have played an enormous role in shaping our forests. Human influences — including frequent, seasonal, anthropogenic fire — provided the conditions whereby trees could reach old ages.

Human influences gave rise to our old-growth. That’s a stunning finding. It contradicts the old paradigm of forest development, which is based entirely on non-human factors. But the old paradigm is wrong. Too many anomalies exist in the real world, such as thickets of fir underneath ancient overstories of pine. The old paradigm cannot explain how natural forces alone created those (species-specific multicohort) forest conditions. The new paradigm, which accepts historical human influences as significant, does explain how our old-growth forests came to exist.

That’s an ecological issue. The old ecology is wrong. The new ecology is a vast improvement.

The Northwest Forest Plan is based on out-dated and incorrect assumptions about forest ecology. It is no wonder that the NWFP has failed; the scientists who crafted it were deficient in their understanding about how our forests developed.

Restoration forestry seeks to restore the actual, historical forest development pathways within the actual watersheds where that development took place. That is why restoration forestry stands a chance of succeeding where the NWFP and old paradigm ecology has failed so miserably and catastrophically.

We are encouraged by Mr. Partin’s call for a new approach, and in turn we encourage him to seek a greater understanding of what restoration forestry is, where its basis lies, and why it might succeed where the old approach has failed.

We encourage Mr. Partin, and all others, to review the papers in the W.I.S.E. Colloquia History of Western Landscapes [here], Restoration Forestry [here], Forest and Fire Sciences [here], and Wildlife Sciences [here].

Our Colloquia are works in progress. We have not gotten all the key papers up yet, but what we have posted so far should give readers a good introduction to new paradigm thinking.

We encourage Mr. Partin, and all others, to ask questions. That’s how learning occurs.

If more people begin to understand the new findings, the new ecology, and the new techniques of restoration forestry, then the “new approach” will become clearer. We won’t have to wonder what that new approach might be, nor be stuck any longer in the failed approaches of the past.

Forestry education Restoring cultural landscapes Saving Forests The 2010 Fire Season

by admin

leave a comment

Too Little, Too Late to Save Flagstaff’s Forests

An article about the Shultz Fire from Northern Arizona University:

NAU experts weigh in on lessons of Schultz Fire

Inside NAU, June 30, 2010 [here]

Expected to be fully contained today, the Schultz Fire [here] that scorched more than 15,000 acres in northeast Flagstaff and captured worldwide attention is human caused in more ways than one, said Northern Arizona University experts.

“This is a human caused fire from two perspectives,” said Daniel Laughlin, a research associate with the university’s Ecological Restoration Institute [here]. “A human campfire was left to burn in an ecosystem that became dense because of 100 years of mismanagement.”

A century of fire suppression has successfully kept fire off the peaks—a landscape dominated by ponderosa pine, which typically burn every two to 45 years. The blaze torched an area not burned since the 1890s in an ecosystem historically subject to frequent, low intensity fires.

There is a glaring misstatement in that.

Historically, the ecosystem was subject to frequent, seasonal anthropogenic fires. i.e. set by the indigenous residents.

I don’t know why ERI is so reticent to admit or even to investigate the historical forest development pathways in what is so clearly an ancient cultural landscape. It’s not like their host institution, Northern Arizona University, is equally deaf, dumb, and blind to the former inhabitants of the San Francisco Peak area (i.e. Flagstaff vicinity). See:

Dating Wupatki Pueblo: Tree Ring Evidence [here]

San Francisco Mt. Ware [here]

The Hopi’s, whose home mesas are east of Flagstaff, consider the San Francisco Peaks (Nuvatukya’ovi) to be sacred mountains. In fact, the Peaks are held sacred by over 13 Native American Nations [here].

The Tribes claim ownership and residency going back many hundreds of generations. There is no reason to doubt their veracity, since archaeological relics are frequent and widespread in the area. The Forest Service has identified the Peaks as a Traditional Cultural Property. It’s common knowledge that people have been living there for millennia.

It would be safe to assume that the native residents practiced landscape burning, since every other indigenous tribe in the Southwest (and elsewhere) burned their homelands regularly. And it is clear to many observers that frequent anthropogenic fire led to open, park-like forests and prairies. Putting those two well-known facts together leads to the inexorable conclusion that anthropogenic fire shaped the vegetation in the pine forests of Flagstaff.

Ancient Human Environmental Influences In Yellowstone

It turns out that Yellowstone is not a pristine, untrammeled wilderness after all.

Science Daily reported today that a 10,000-year-old hunting shaft (atlatl dart) has been discovered in the Rockies near Yellowstone.

Hunting Weapon 10,000 Years Old Found in Melting Ice Patch

ScienceDaily, June 29, 2010, [here]

To the untrained eye, University of Colorado at Boulder Research Associate Craig Lee’s recent discovery of a 10,000-year-old wooden hunting weapon might look like a small branch that blew off a tree in a windstorm.

Nothing could be further from the truth, according to Lee, a research associate with CU-Boulder’s Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research who found the atlatl dart, a spear-like hunting weapon, melting out of an ice patch high in the Rocky Mountains close to Yellowstone National Park.

The US Forest Service didn’t invent Let It Burn, the National Park Service (NPS) did.

The most infamous Let It Burn fires in our National Parks were the Yellowstone Fires of 1988 when 1.2 million acres (1,875 square miles) of Greater Yellowstone were proudly incinerated by the NPS.

It is not a stretch to say “proudly” because the NPS gushes all over itself for the Yellowstone Fires [here].

Among the justifications presented by the NPS for the Yellowstone Fires was that the fires were “natural”, as if “natural” made any difference.

The natural history of fire in the park includes large-scale conflagrations sweeping across the park’s vast volcanic plateaus, hot, wind-driven fires torching up the trunks to the crowns of the pine and fir trees at several hundred-year intervals.

Such wildfires occurred across much of the ecosystem in the 1700s. But that, of course, was prior to the arrival of European explorers, to the designation of the park, and the pattern established by its early caretakers to battle all blazes in the belief that fire suppression was good stewardship.

That bit of racist nonsense fails to mention that Native Americans had been residing in and visiting the Yellowstone region for at least 11,900 years. The “early caretakers” were not the NPS!!! The actual early acretakers set frequent, seasonal, non-catastrophic fires that precluded holocausts like 1988.

The ignorant racism was readily adopted by NPS “scientists” too:

…[B]y the 1970s Yellowstone and other parks had instituted a natural fire management plan to allow the process of lightning-caused fire to continue influencing wildland succession. …

Only a miniscule portion of once vast wilderness landscapes has been preserved, and the boundaries and spatial extent of these preserved bear little relationship to the natural processes necessary for their preservation. The 1988 fires have laid bare the broad extent of our ignorance of those natural processes. — N. A. Christensen, et al.

The NPS is profoundly ignorant of the historical human influences on ecosystem development in all of our national parks. They have blinders on in that regard. NPS fires wipe out any trace of the real natural history on those landscapes. It’s more than ignorance — it’s their deliberate policy to do so. That is because the foundational conceit of the NPS is the American Creation Myth: God made the Wilderness for the Salvation of Humanity, specifically Euro immigrants as paternally cared for by NPS neo-Victorian elitists.

But Yellowstone is not wilderness. Modern (non-NPS) scientists are well-aware of the historical human environmental influences in the Yellowstone and the non-wilderness (homelands) quality of that cultural landscape.

The newly discovered atlatl dart is proof that human beings have been living in the Yellowstone area for (at least) 10,000 years. It is proof that for millennia human beings have been the key predators, the most effective and deadly hunters, armed with advanced technology capable of killing any other animal.

The dart is circumstantial evidence that human beings have controlled animal populations in the Yellowstone area for 10,000 years.

Because human beings everywhere, for our entire existence as a species, also employed landscape anthropogenic fire, the atlatl dart is circumstantial evidence that human beings have been burning Yellowstone deliberately, frequently, for survival purposes, for 10,000 years.

The Science Daily article continues:

Later this summer Lee and CU-Boulder student researchers will travel to Glacier National Park to work with the Salish, Kootenai and Blackfeet tribes and researchers from the University of Wyoming to recover and protect artifacts that may have recently melted out of similar locations.

“We will be conducting an unprecedented collaboration with our Native American partners to develop and implement protocols for culturally appropriate scientific methods to recover and protect artifacts we may discover,” he said.

Modern Native Americans, archaeologists, historians, and cultural experts recognize the continuity of human occupation of the landscape for many hundreds of generations. It wasn’t until the Euro-Victorians came along that humanity was driven off the land.

An important component of restoration is the reintroduction of humanity into the landscape, including the restoration of human-nature connections and traditional practices. Thus restoration is at odds with the American Creation Myth and with the NPS policy of denying human heritage and historical human influences on the environment.

Restoration seeks to restore the anthropogenic fire and anthropogenic wildlife management extant for the entire Holocene, save the last 150 years or so. That is why the current NPS policy of banning hunting and allowing catastrophic lightning fires to incinerate watersheds during the peak summer months is anathema to restorationists.

We look at the myth-bound, arguably racist, definitely destructive policies of the NPS and wonder how such horrific policies ever became ingrained, and how we might shake the NPS out of it’s ignorance and destructiveness.

Anthropogenic Fire in Tasmania

At what is seemingly the end of the world sits the island of Tasmania. It is 150 miles south of Australia, separated by the Bass Strait, and thought by some to be the epitome of pristine, untouched nature. Not counting the modern cities, towns, farms, etc., of course.

As remote as it is, however, Tasmania has been home to humanity for at least 35,000 years. In fact, until the world’s ocean rose after the Wisconsin Glaciation some 10,000 years ago, Tasmania was a peninsula connected to mainland Australia.

The Palawa people (Tasmania aborigines, [here]) were first decimated by old-world diseases and then rounded up and exiled to Flinders Island in the 1830’s. But before those unfortunate events, they managed to survive in isolation for millennia with stone age tools.

And as SOSF readers know, the principal stone age survival tool, going back into hoary antiquity to our proto-human ancestors a million years or more removed, has been fire.

Every culture on Earth has used fire to alter their environments for various survival-enhancement purposes, and the Palawa were no different. A wonderful essay about pre-Contact anthropogenic fire in Tasmania is:

Gammage, Bill. 2008. Plain Facts: Tasmania under Aboriginal Management. Landscape Research, Vol. 33, No. 2, 241 – 254, April 2008.

now posted in the W.I.S.E. Colloquium: History of Western Landscapes [here].

Yes, I know, Tasmania is hardly “western”. But the history is similar and instructive.

Professor Bill (William Leonard) Gammage is a visiting fellow in the Humanities Research Centre, Australian National University, studying Aboriginal attitudes to land and land management from a historical perspective. His books include ‘The Broken Years: Australian Soldiers in the Great War’ (1974), ‘The Sky Travellers. Journeys in New Guinea 1938-39′ (1998), and ‘Narrandera Shire’ (1986) [here].

So he knows how to write, and what’s more, his essay has great pictures, too! The Abstract:

Almost all researchers now accept that Australia’s Aborigines were managing their country with the broad-scale use of fire when Europeans arrived. In respect to Tasmania, this article goes further, arguing that fire was not merely broad-scale, but applied variably and precisely, to make, then connect, a complex range of useful ecosystems. The article also argues that Aboriginal land management must be seen in cultural as well as ecological terms.

In SOSF lingo, that means Tasmania was a vintage cultural landscape intentionally modified into an anthropogenic mosaic by intelligent torch bearing humans.

More Geoglifo Photos

Geoglifos are ancient geometric earthen structures in Amazonia, built by civilizations that thrived hundreds and even thousands of years ago in what today is widely but incorrectly thought of as “wilderness”.

An example of geoglifos found in Acre, Amazonas, and Rondonia states. Photo courtesy Dr. William Woods. Click for larger image.

The clear implication is that the forest wasn’t there 500 years ago, but lots of people were! Many of the geoglifos are connected by kilometers of causeways or moat-like features. Photo courtesy Dr. William Woods. Click for larger image.

For additional photos, discussion, reports, and book reviews on pre-Columbian geometric earthworks in Amazonia see [here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here].

Federal forest policy Politics and politicians Restoring cultural landscapes Saving Forests

by admin

leave a comment

Wyden Eastside Forest Bill Unworkable

Note: the following essay has been submitted to the Oregonian in response to their unsigned editorial of June 8, 2010 [here]

To the Oregonian Editorial Board

Your editorial “The wrong place to drive a wedge” of June 4 is naive and disengenuous. The facts regarding Sen. Ron Wyden’s “Eastside Forest Compromise” are these:

1. The compromise was engineered between two minority factions of two special interest groups. Those factions do not represent the interest of their respective groups, which in turn do not represent the interests of the greater public, who are the actual owners of the land.

2. As such, the compromise will not be successful in averting litigation. Excluded groups such as the Sierra Club have already announced their intention to litigate any timber sales created under Wyden’s program, should it become law.

3. Politicization is a fact of life in major forest initiatives. Wyden’s compromise does not de-politicize anything, nor should it, and your call to remove this issue from the political dialog is ill-considered. Debate is an essential element of democratic society. Squelching debate is contrary to our American political system.

4. Forest restoration is already the law. The Forest Landscape Restoration Act of 2009 (Title IV of the Omnibus Public Lands Act of 2009) calls for restoration on a landscape scale, with Technical Advisory oversight, on a national basis. Wyden voted for the FLRA but has fought against funding it. His bill duplicates many of the provisions, undermines others, and inserts poison pill clauses where none exist in the current law.

5. Wyden’s bill contains prescriptive language that violates NEPA and NFMA, proposes management guidance that is unscientific and unworkable, does not protect (increases risks to) vegetation, habitat, wildlife, water, air, soils, and other ecological values, and does not protect (increases risks to) heritage, utility, resiliency, sustainability, public health and safety, private property, and other human values.

6. Wyden’s bill establishes “local forests” managed under separate laws and overseen by duplicative advisory panels, yet financed with federal dollars and staffed with federal employees, that supplant current statutory mandates for planning and management processes. It establishes a new law that conflicts with existing laws and does not address systemic problems with the USFS mission.

7. Wyden’s bill is unworkable, and hence not one stick of timber will ever be cut under its provisions. It thereby creates unrealistic expectations on the part of communities and forest stakeholders, will draw action and funding away from other projects, and will delay unnecessarily desperately need treatments to reduce the threat of catastrophic fire.

Forest restoration is already the law. Wyden and the Oregonian need to support the Act he already voted for and not seek to undermine it with obfuscatory gamesmanship. U.S. Senate candidate James Huffman is correct in his critical assessment of Wyden’s bill, joining with Harris Sherman, Undersecretary of Agriculture for Natural Resources and Environment, Jack Ward Thomas, former Chief of the US Forest Service, many current and retired USFS officials, and numerous forestry experts well-versed in the issues.

Mike Dubrasich, Exec Dir W.I.S.E.

33862 Totem Pole Rd.

Lebanon, OR 97355

https://westinstenv.org

The Western Institute for Study of the Environment is a 501(c)(3) non-profit educational corporation and a collaboration of environmental scientists, resource professionals and practitioners, and the interested public.

Our mission is to further advancements in knowledge and environmental stewardship across a spectrum of related environmental disciplines and professions. We are ready, willing, and able to teach good stewardship and caring for the land.

W.I.S.E. provides a free, on-line set of post-graduate courses in environmental studies, currently fifty topics in eight Colloquia, each containing book and article reviews, original papers, and essays. In addition, we present three Commentary sub-sites, a news clipping sub-site, and a fire tracking sub-site. Reviews and original articles are archived in our Library.

A Setback for Forest Restoration

Tribe, conservation groups sue Six Rivers National ForestBy Don Baumgart, Indian Country Today, Jun 8, 2010 [here]

ORLEANS, Calif. – The Karuk Tribe of northern California has filed suit against Six Rivers National Forest Supervisor Tyrone Kelley, charging in Northern California District Court that the U.S. Forest Service has violated the National Historic Preservation Act by doing heavy equipment logging in areas sacred to the tribe.

“We participated in good faith in the Forest Service’s collaborative process and we were assured that our sacred areas would be protected and our cultural values respected,” said Leaf Hillman, the tribe’s natural resources director. “It’s now obvious that those were hollow promises.”

According to the final Environmental Impact Statement for the project, the stated purpose and need for the fuel reduction effort is to “manage forest stands to reduce fuels accumulation and improve forest health around the community of Orleans”

However, the actual work on the ground is clearly inconsistent with these stated goals, according to Hillman.

“Supervisor Kelly and the Forest Service have already destroyed cultural sites that are still used by the tribe during World Renewal Ceremonies.”

“After years of meetings between officials from Six Rivers National Forest, the Karuk Tribe, conservation groups and community members, details of the Orleans Community Fuels Reduction Plan were agreed upon,” said Craig Tucker, tribe spokesman. “However, last fall when Supervisor Tyrone Kelley directed his crews to begin logging with heavy equipment in areas sacred to the Karuk Tribe, they violated the agreement and federal law, betraying the trust of local landowners.”

Involved in the suit are 914 acres to be mechanically harvested. The Forest Service awarded the contract to Timber Products for nearly $1 million. Outraged tribal members and local residents halted work on the project last November by blockading logging roads that access the units to be cut.

For three years the Orleans Ranger District in California’s Six Rivers National Forest held public meetings to work with the Orleans community to develop a fuels reduction plan that both Native and non-Native community members could accept, Tucker said. Tribal members, as well as non-Native local residents, thought a consensus had been reached.

“However, when logging began last fall, community members realized immediately that Kelly had reneged on his promises and violated the law by implementing a plan inconsistent with his own Environmental Impact Statement,” Tucker said. … [more]

This is a tragic tale of good intentions and USFS incompetency.

On paper, the Orleans Community Fuels Reduction and Forest Health Project was a good idea. The project was exemplary even, a cutting-edge cultural landscape restoration project. But the leadership of the Six Rivers NF managed to screw it up big time.

Federal forest policy Restoring cultural landscapes Saving Forests

by admin

2 comments

Jerry Williams On Megafires

What exactly are megafires? Why do they happen? Can they be prevented? When is the next one going to occur and where?

Those questions and similar ones were explored at the annual meeting of the Inland Empire chapter of the Society of American Foresters last month in Wallace, Idaho.

Perhaps no one has more insight into megafires than Jerry T. Williams, retired U.S. Forest Service, former Director, USFS Fire & Aviation (the highest ranking fire officer in the country). He presented a paper entitled The 1910 Fires A Century Later: Could They Happen Again?. Selected excerpts and a link to the full text are [here].

Some background: in 1910 a firestorm swept across Washington, Idaho, and Montana. In just 48 hours 3 million acres were burned, 85 people killed, and five towns destroyed in a sparsely populated region.

Dr. Stephen J. Pyne wrote the scholarly history of the harrowing tale in Year of the Fires: The Story of the Great Fires of 1910, 2001 Viking Press [here]. Jim Petersen, co-founder and Executive Director of the non-profit Evergreen Foundation gave a fine lecture on the topic [here]. Bruce Vincent, Tom Boatner, yours truly [here], and many others have weighed in on the likelihood of another “category five” firestorm in the Northern Rockies.

This year, the 100-year anniversary of The Big Blowup, has seen quite a few memorial events and seminars. The Inland Empire SAF meeting may have been the most notable of those, and Jerry Williams’ paper the most perceptive commentary yet on whether such a megafire could happen again.

His very expert conclusion is yes, yes indeed.

Mr. Williams bases his conclusion in part on the findings of the Mega-Fire Project, a study of nine megafires that occurred across the United States between 1998 and 2007: Volusia-Flagler Complex (205,786 acres, Florida 1998); Valley Complex (212,030 acres, Montana 2000); Hayman Fire (137,760 acres, Colorado 2002); Rodeo-Chedeski Fire (468,638 acres, Arizona 2002); Biscuit Fire (499,965 acres, Oregon 2002); Ponil Complex (92,522 acres, New Mexico 2002); Georgia Bay Complex/Bugaboo (561,000 acres, Georgia and Florida 2007); Boise National Forest portion of the Cascade Complex (302,376 acres, Idaho 2007).

He raises some key issues, many of which we have discussed at length here at SOS Forests, but which are worthy of reconsideration:

* Virtually all of the mega-fires evaluated in this assessment occurred in predominantly dense, late-successional forests. At the landscape-scale, these forests had remained largely un-disturbed for a long time.

* Although mega-fires burned across a wide variety of habitat types and fire regimes, a significant portion of the overall mega-fire acreage studied in this assessment occurred in shorter interval fire-dependent ecosystems, much altered from their historic condition…

* On many mega-fire landscapes, the forest conditions that fueled these severe, high-intensity wildfires were often reflected in governing land-use objectives. On public lands, they were called-for in Land and Resource Management Plans. …

* In virtually every case, the values that were being managed for were lost or severely compromised, as a result of the mega-fire’s impacts. …