Criminal Activities by Federal Bureaucrats and Others Involved in the Introduction, Protection and Spread of Wolves in the Lower 48 States

Beers, Jim. 2010. Criminal Activities by Federal Bureaucrats and Others Involved in the Introduction, Protection and Spread of Wolves in the Lower 48 States. Friends of the Northern Yellowstone Elk Herd, Bozeman, MT 16 May 2010.

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

Abstract:

The period 1967 to 1999 saw the passage of 3 Endangered Species Acts and a tightening of federal authority over a host of plants and animals formerly under the jurisdiction of state governments. Mr. Beers was employed by the US Fish and Wildlife Service in many capacities and locations during this period. He explains the growth of federal power, the shift in the sort of employees and agendas responsible for the federal growth, and the resulting subversion of state fish and wildlife agencies and any respect for law by increasingly powerful bureaucrats. The introduction, protection, and spread of wolves by federal decrees during this period are detailed and major violations that occurred are explained. The violations include the theft of $60+ of excise tax money by federal bureaucrats from state fish and wildlife programs to introduce wolves, Non-governmental organization entanglements with federal bureaucrats and federal funds, quid pro quo arrangements with state bureaucrats, failure to audit state fish and wildlife programs in order to maintain state compliance with illegal federal actions, failure of federal bureaucrats to describe and forecast the impacts and costs of introduced wolves, and the cover-up of millions of dollars of state misuse of federally-collected excise taxes.

Introduction:

The following two-hour verbal presentation is divided into three parts. This is so that the listener or reader understands three things.

First is the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) time of employment of the author and his competency concerning this subject. This is important for you to appreciate the competency of the author to speak about federal environmental/animal rights policies, federal bureaucracies and their operation, the changing nature of federal and state fish and wildlife programs, and the impacts that these changes are continuing to have on our American society.

Second are the political, scientific, and legal changes of the past 40 years and how their cumulative impacts have led to the corruption and disregard for both US law and the US Constitution described in the third part.

Third is a description of law violations by both those immediately involved in the introduction, protection, and spread of wolves in the Upper Great Lake States, the Carolinas, the SW States, the Upper and Central Rocky Mountain States and the resulting and ever-widening range of associated bureaucrats’, agencies’, and associated “partners’” activities continuing in disregard of federal laws.

Descriptions and explanations of the growing danger of wolf attacks; the purposeful lack of information about wolves as carriers of diseases that infect and kill humans, livestock, and wildlife; the annihilation of big game animals, big game hunting, and hunting revenues to state wildlife agencies; the widespread destruction of pets and working dogs; and the ruination of the tranquility of rural life where wolves exist are topics that are being addressed in detail elsewhere.

This presentation is intended to describe criminal activities by federal and state bureaucrats, lobbyists, and radical organizations associated with the establishment, protection and spread of wolves in the Lower 48 states. It is my belief that understanding this aspect of the wolf issue will enable all of us to better understand and work more effectively to solve the myriad problems that government bureaucrats, activist organizations, and politicians have caused by illegal actions disguised as wolf introduction and protection.

Idaho Wildlife Services Wolf Activity Report 2009

U.S. Department of Agriculture

Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service

Wildlife Services

USDA-APHIS IDAHO WILDLIFE SERVICES WOLF ACTIVITY REPORT FISCAL YEAR 2009

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

Introduction

This report summarizes Idaho Wildlife Services’ (WS) responses to reported gray wolf depredations and other wolf-related activities conducted during Fiscal Year (FY) 2009 (October 1, 2008 – September 30, 2009) pursuant to Permit No. TE-081376-12, issued by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) June 16, 2006. This permit allows WS to implement control actions for wolves suspected to be involved in livestock depredations and to capture non-depredating wolves for collaring and re-collaring with radio transmitters as part of ongoing wolf monitoring and management efforts. …

Results

Brief summaries that pertain to those investigations which resulted in a finding of confirmed or probable wolf damage are available on request from the ID WS State Office.

Investigations Summary: WS conducted 226 depredation investigations related to wolf complaints in FY 2009 (as compared to 186 in 2008, an increase of almost 22%). Of those 226 investigations, 160 (~71%) involved confirmed depredations, 43 (~19%) involved probable depredations, 16 (~7%) were possible/unknown wolf depredations and 7 (~3%) of the complaints were due to causes other than wolves.

Based on Idaho WS investigations, the minimum number of confirmed and probable livestock depredations due to wolves in FY 2009 was:

Confirmed

76 calves (killed), 7 calves (injured)

14 cows (killed)

344 sheep (killed), 20 sheep (injured)

16 dogs (killed), 8 dogs (injured)

1 foal (killed), 1 goat (killed)

Probable

26 calves (killed), 3 calves (injured)

1 cow (killed)

156 sheep (killed)

4 dogs (killed), 2 dogs (injured)

1 goat (killed)

The number of both cattle and sheep killed and injured by wolves in FY 2009 was the highest ever recorded. The number of cattle killed and injured was only slightly higher than in FY 2008, but there was a dramatic increase in the number of sheep killed and injured, as compared to FY 2008 (Figure 2). Although there were more incidents of wolf predation on cattle than on sheep (Figure 3), the tendency for wolves to kill multiple sheep per incident contributed to the greater numbers of sheep killed. Wolf depredations on cattle and calves more often involve attacks on just a single animal per incident.

Deer, Elk, Bison Population Dynamics Research Methods Wildlife Management

by admin

Comments Off

The Art and Science of Counting Deer

Charles E. Kay. 2010. The Art and Science of Counting Deer. Muley Crazy Magazine, March/April 2010, Vol 10(2):11-18

Full text:

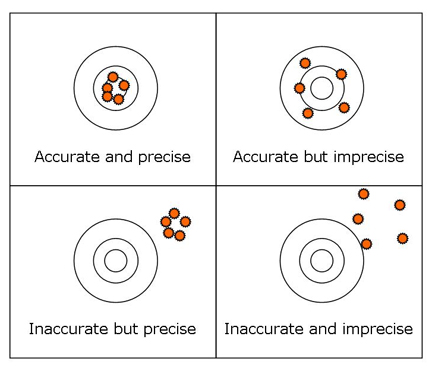

It is the simplest of questions and upon which all management is based. It is also the first thing most hunters want to know. How many deer are there? The answer? Well, there are no answers, only estimates. In addition, one needs to understand the difference between precision and accuracy. Think of precision as shooting a five-shot, half-inch group at 100 yards, but the group is 20 inches high and to the right. The shots have been very precise, almost in the same hole, but they were not accurate because they were far from the center of the target. Accuracy is hitting the bullseye. So, an estimate can be precise without being accurate. Estimates that are both precise, low variation, and accurate, close to the true number, are very difficult and very expensive to obtain. Moreover, all population estimates contain assumptions, as well as sampling errors and statistical variation.

Since the advent of modern game management, various methods have been developed to count wildlife. Entire books have been written on the subject and there are enough scientific studies to fill a small library. Here, I will discuss only the techniques that have been, or are commonly used to estimate the number of mule deer and elk on western ranges. This includes ground counts, aerial surveys, population models, pellet-group counts, and thermal imaging.

The oldest and simplest method is ground counts. As the name implies, these are simply counts conducted on foot, horseback, or from vehicles by either one or more observers. While relatively inexpensive, this method is neither precise nor accurate. There is the problem of double counting when the deer run over the hill into the next canyon that has not yet been surveyed and under counting when animals are hidden from view by vegetation or topography. Today, ground counts are seldom used to estimate herd numbers but they are still commonly employed to estimate fawn:doe ratios or buck:doe ratios under the assumption that doe, fawn, and buck sighting rates are similar, which they are not. If bucks are more difficult to see than does because of the habitat the males occupy, or their behavior, ground counts will underestimate the number of bucks.

Due to the shortcomings of ground counts, wildlife biologist were quick to take to the air, first in airplanes and later in rotary aircraft. To make a long story short, counts from helicopters are more accurate than population surveys from fixed-wings. Any aerial count, though, is subject to errors, because even from the air you do not see all members of a population, be they mule deer or elk. This is what, in the scientific literature, is known as sightability bias. Even in experiments where livestock have been placed in flat, grassy pastures, aerial observers fail to record all the animals.

Lessons from a Transboundary Wolf, Elk, Moose and Caribou System

Mark Hebblewhite. 2007. Predator-Prey Management in the National Park Context: Lessons from a Transboundary Wolf, Elk, Moose and Caribou System. Predator-prey Workshop: Predator-prey Management in the National Park Context, Transactions of the 72nd North American Wildlife and Natural Resources Conference.

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

Introduction

Wolves (Canis lupus) are recolonizing much of their former range within the lower 48 states through active recovery (Bangs and Fritts 1996) and natural dispersal (Boyd and Pletscher 1999). Wolf recovery is being touted as one of the great conservation successes of the 20th century (Mech 1995; Smith et al. 2003). In addition to being an important single-species conservation success, wolf recovery may also be one of the most important ecological restoration actions ever taken because of the pervasive ecosystem impacts of wolves (Hebblewhite et al. 2005). Wolf predation is now being restored to ecosystems that have been without the presence of major predators for 70 years or more. Whole generations of wildlife managers and biologists have come up through the ranks, trained in an ungulate- management paradigm developed in the absence of the world’s most successful predator of ungulates—the wolf. Many questions are now facing wildlife managers and scientists about the role of wolf recovery in an ecosystem management context. The effects wolves will have on economically important ungulate populations is emerging as a central issue for wildlife managers. But, questions about the important ecosystem effects of wolves are also emerging as a flurry of new studies reveals the dramatic ecosystem impacts of wolves and their implications for the conservation of biodiversity (Smith et al. 2003; Fortin et al. 2005; Hebblewhite et al. 2005; Ripple and Beschta 2006; Hebblewhite and Smith 2007).

In this paper, I provide for wildlife managers and scientists in areas in the lower 48 states (where wolves are recolonizing) a window to their future by reviewing the effects of wolves on montane ecosystems in Banff National Park (BNP), Alberta. Wolves were exterminated in much of southern Alberta, similar to the lower 48 states, but they recovered through natural dispersal populations to the north in the early 1980s, between 10 and 20 years ahead of wolf recovery in the northwestern states (Gunson 1992; Paquet, et al. 1996). Through this review, I aim to answer the following questions: (1) what have the effects of wolves been on population dynamics of large-ungulate prey, including elk (Cervus elaphus), moose (Alces alces) and threatened woodland caribou (Rangifer tarandus tarandus), (2) what other ecosystem effects have wolves had on montane ecosytems, (3) how sensitive are wolf-prey systems to top-down and bottom-up management to achieve certain human objectives, and (4) how is this likely to be constrained in national park settings? Finally, I discuss the implications of this research in the context of ecosystem management and longterm ranges of variation in ungulate abundance. …

The Kaibab Deer Incident: Myths, Lies, and Scientific Fraud

Charles E. Kay. 2010. The Kaibab Deer Incident: Myths, Lies, and Scientific Fraud. Muley Crazy Jan/Feb 2010 (posted with permission of the author).

Full text:

The North Kaibab, or simply the Kaibab, is famous for producing large-antlered, record-book mule deer. The Kaibab historically, however, is also noted for something else — controversy! At least one book has been written on the Kaibab Deer Incident, as well as scores of scientific reports and monographs. The Kaibab figures prominently in the history of mule deer management in the West and even the U.S. Supreme Court has weighed-in on the Kaibab. Although the story has changed over the years, the Kaibab is still discussed in wildlife textbooks and the ghost of the Kaibab stalks wildlife management to this day.

The Kaibab Plateau is bordered on the south by the Grand Canyon, on the west by Kanab Canyon, and on the east by Houserock Valley. The plateau, which is entirely in Arizona, slopes gently downward to the north and ends near the Utah stateline. The plateau reaches a height 9,200 feet and although the Kaibab receives abundant snow and rainfall, surface water is exceedingly rare due to area’s geology. Winter range is abundant on the Kaibab, while summer range is more limited-the exact opposite of most western situations. Approximately two-thirds of the mule deer on the Kaibab winter on the westside with the remaining deer wintering to the east. There is very little movement of mule deer into Utah. Thus, the deer herd on the Kaibab is essentially an insular population with little immigration or emigration. Cliffrose is the most important browse species on the plateau’s shrub-dominated winter ranges.

The Kaibab was established as a Forest Reserve in 1893 and in 1906 was designated as the Grand Canyon National Game Preserve by President Theodore Roosevelt. Today, the southern end of the plateau is in Grand Canyon National Park, while the rest of the area is managed by the U.S. Forest Service. When the Kaibab was declared a game preserve in 1906, hunting was prohibited and the federal government began an extensive predator control program. Between 1907 and 1923, an average of 40 mountain lions, 176 coyotes, 7 bobcats, and 1 wolf were killed each year. In all, only 30 wolves were ever killed by government agents on the Kaibab. Instead, the main predators were mountain lions and coyotes. The Forest Service also reduced the number of livestock permitted to graze the plateau.

In response to those measures, the mule deer herd irrupted from around 4,000 animals in 1906 to an estimated 100,000 head in 1924. As might be expected, the growing deer population severely overgrazed both the summer and winter ranges. This lead to a number of studies and reports, as well as a dispute between the federal government and the state of Arizona. In short, the Forest Service said that the deer herd needed to be reduced to prevent further range damage but the state refused to open the area to hunting. In response, the federal government claimed that it could kill deer on the Kaibab to protect habitat without a state permit. Needless to say, Arizona objected and the ensuing legal battle made it all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court agreed that the Kaibab deer herd had exceeded the range’s carrying capacity and that overgrazing by mule deer had denuded public lands. The Court also sided with the federal government in ruling that the Forest Service could authorize hunting on the Kaibab without state approval. This legal precedent still stands and means that when push come to shove, the federal government can control wildlife populations on public lands. Arizona had no alternative but to capitulate, but it was too late because the plateau’s mule deer had experienced a major die-off and by 1931 fewer than 20,000 animals were left.

For years, the Kaibab deer irruption, overgrazed range, and subsequent die-off were cited in wildlife textbooks as a classic example of what happens when predators are controlled and hunting eliminated. “The Terrible Lesson of the Kaibab” became a cornerstone of modern game management and an example of why hunters were needed to harvest surplus animals. Even Aldo Leopold cited the Kaibab in his study of mule deer overgrazing on western ranges. This interpretation of the Kaibab Deer Incident was accepted as fact for over 40 years until New Zealand biologist Graeme Caughley questioned its validity in a 1970 paper published in Ecology-the scientific journal of the Ecological Society of America. Caughley’s reanalysis of the Kaibab Deer Incident involved primarily published mule deer population estimates. In a later paper, Caughley admitted that he had never set foot on the Kaibab and that he had conducted his reanalysis from a desk 10,000 miles away! Caughley cautioned that his “interpretation may therefore be wrong.”

Deer, Elk, Bison Population Dynamics Predators Wildlife Habitat Wildlife Management Wildlife Policy

by admin

Comments Off

Wolf Predation: More Bad News

Charles E. Kay. 2008. Wolf Predation: More Bad News. Muley Crazy, Sept/Oct 2008 (posted with permission of the author).

Full text:

As I explained in an earlier article, pro-wolf advocates are now demanding 6,000 or more wolves as one interbreeding population in every western state. Pro-wolf advocates also claim that predation, in general, and wolves in particular have no impact on prey populations. Recent research by Dr. Tom Bergerud and his colleagues, however, paints an entirely different picture and serves as a poignant example of what will happen to the West’s mule deer if pro-wolf advocates have their way.

Woodland and mountain caribou have been declining throughout North America since European settlement. Many attribute the decline to the fact that caribou must feed on aboral or terrestrial lichens during winter, a food that is being destroyed by logging, forest fires, and other human activities; i.e., modern landuse practices are to blame. While others attribute the decline to predation by wolves and other carnivores. To separate between these competing hypotheses, Dr. Tom Bergerud and his co-workers designed a series of simple but elegant experiments and have now accumulated 30 years of data.

In the northern most arc of Lake Superior lie a cluster of seven major islands plus smaller islets. The Slate Islands are five miles from the mainland at their nearest point and only twice during the last 30 years has winter ice bridged that gap. Terrestrial lichens are absent, plus the islands have been both logged and burned, making them unfit for caribou according to most biologists. The Slate Islands lack wolves, black bears, whitetailed deer, and moose, but caribou are indigenous. As a companion study, Bergerud and his associates chose Pukaskwa National Park, which stretches for 50 miles along the north shore of Lake Superior. In contrast to the Slate Islands, Pukaskwa has an abundance of lichens, which are supposed to be a critical winter food for caribou, but unlike the Slate Islands, Pukaskwa is home to wolves, bears, moose, and whitetails. Woodland caribou are also present.

So we have islands that are poor caribou habitat, but which have no predators, versus a nearby national park that is excellent caribou habitat but which contains wolves. Now according to what many biologists and pro-wolf advocates would have you believe, habitat is the all important factor in maintaining healthy ungulate populations, while predation can largely be ignored. Well, nothing could be further from the truth. Habitat it turns out, is irrelevant and ecologists have been, at best, braindead for years.

Despite the supposedly “poor” habitat in the Slate Islands, Bergerud and his research team recorded the highest densities of caribou ever found anywhere in North America. Moreover, those high densities have persisted since at least 1949 when the herd was first censused. More importantly, the density of caribou in the “poor” habitat, but predator-free, Slate Islands was 100 times that in Pukaskwa National Park where predators hold sway. 100 times or 10,000% more caribou per unit area. A significant difference by any objective standard.

Then during the winter of 1993-94, a natural experiment occurred when Lake Superior froze and two wolves crossed to the Slate Islands. Within days, the two wolves proceeded to cut through the Slate Island caribou like a hot knife through butter. Because caribou, like mule deer, are exceedingly susceptible to wolf predation. Only when the two wolves disappeared did caribou numbers recover.

A second set of manipulated experiments was conducted when Bergerud and his associates transplanted Slate Island caribou to adjoining areas with and without wolves. A release to Bowman Island, where wolves and moose were present, failed due to predation. A second release to Montreal Island doubled in numbers until Lake Superior froze and wolves reached that island. A third release was to Michipicoten Island where wolves were absent but so too were lichens. Despite the “poor” habitat, those caribou increased at an average annual rate of 18% for nearly 20 years. A fourth release to Lake Superior Provincial Park on the mainland failed due to wolf predation. Thus, the data are both conclusive and overwhelming. Habitat is largely irrelevant because caribou numbers are limited by wolf predation. Bergerud goes so far as to say that managers have wasted the last 50 years measuring lichens! Remove the wolves and you have 100 times more caribou, even on supposedly “poor” ranges.

Deer, Elk, Bison Predators Wildlife Management Wildlife Policy

by admin

Comments Off

The Complexities of State Management of Wildlife Under Federal Laws

Budge, Randy*. 2009. The Complexities of State Management of Wildlife Under Federal Laws. Conference of Western Attorneys General, Aug 3-5,2009, Sun Valley, Idaho.

*Randy Budge is an attorney and an Idaho Fish and Game Commissioner. This paper represents his personal views and options, not necessarily that of the entire Idaho Fish and Game Commission or the Idaho Department of Fish and Game.

Full text [here] (4.5 MB)

Selected excerpts:

INTRODUCTION

By far the greatest conservationist of our times was President Theodore Roosevelt, who was driven by a passion to protect wildlife for future generations:

“Wild beasts and birds are by right not the property of the people who are alive today, but the property of the unknown generations whose belongings we have not right to squander.”

In an incredible feat to restore dwindling wildlife and protect wild lands in the early 1900s, Roosevelt was instrumental in bringing under federal protection 230 million acres in the form of 150 national forests, 50 national wildlife refuges, 5 national parks and 18 national monuments. This amounted to an incredible 84,000 acres for each day he was in office. …

A tension has always existed between the rights of the states to manage the wildlife within their borders and the right of the federal government to restrict the taking of wildlife or to otherwise manage wildlife in the national interest. The history of federal and state wildlife legislation exhibits an intricate dance over jurisdiction and the right to manage wildlife.

State wildlife laws are based on the principle states own the wildlife within their borders to be held “in trust” for their citizens. Accordingly, the states have primarily shouldered the responsibility to manage wildlife, and have a proven track record of success. In my opinion, the states are far better suited to manage wildlife within their borders than the lumbering and detached federal bureaucracy because the states are better able to monitor and respond to wildlife needs and threats, and to establish cooperation with landowners and other agencies while recognizing the social values of the residents that regularly interact with wildlife.

Federal wildlife laws generally preempt state laws only when necessary to manage or conserve wildlife species that occupy multiple states. Preemption of state law is an area of considerable complexity to be addressed by a later speaker, so further discussion here is omitted. It should be noted, however, that state laws often expressly include or complement Federal laws such as the Endangered Species Act, whose list of endangered species is usually adopted in full by states in their own legislation of endangered and threatened species. …

The Threat of the Yrmo: The Political Ontology of a Sustainable Hunting Program

Mario Blaser. 2009. The Threat of the Yrmo: The Political Ontology of a Sustainable Hunting Program. American Anthropologist, Vol. 111, Issue 1, pp. 10–20.

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

ABSTRACT

Various misunderstandings and conflicts associated with attempts to integrate Indigenous Knowledges (IK) into development and conservation agendas have been analyzed from both political economy and political ecology frameworks. With their own particular inflections, and in addition to their focus on issues of power, both frameworks tend to see what occurs in these settings as involving different epistemologies, meaning that misunderstandings and conflicts occur between different and complexly interested perspectives on, or ways of knowing, the world. Analyzing the conflicts surrounding the creation of a hunting program that enrolled the participation of the Yshiro people of Paraguay, in this article I develop a different kind of analysis, one inspired by an emerging framework that I tentatively call “political ontology.” I argue that, from this perspective, these kinds of conflicts emerge as being about the continuous enactment, stabilization, and protection of different and asymmetrically connected ontologies. [Keywords: political ontology, multinaturalism, multiculturalism, Paraguay, Indigenous peoples]

INTRODUCTION

In 1999, after four years of a strictly observed ban on commercial hunting, news reached the Yshiro Indigenous communities of Northern Paraguay that the activity would be allowed again under the supervision of the National Parks Direction. Through their recently created federation, Uni´on de las Comunidades Ind´igenas de la Naci´on Yshir, the Yshiro leaders inquired from the Parks Direction about permits to hunt capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris), yacare (caiman sp.), and anaconda (Eunectes notaeus).

They were notified that, although the institution was willing to allow commercial hunting, it actually could not issue the permits as it lacked the necessary resources to send inspectors to supervise the activity. Following the advice from the National Parks Direction, the Yshiro leaders sought support from Prodechaco, an EU–funded sustainable development project that targeted Indigenous peoples. The directors of the Prodechaco agreed to support the Yshiro federation’s bid for hunting permits with the condition that hunting had to be done in a sustainable manner. To make the concept clear, one of them explained in plain words: “The animal population has to be kept constant over the years. You hunt but making sure that there will always be enough animals for tomorrow” (conversation witnessed by author, November 1999).

Espousing a “participatory approach,” Prodechaco framed the relation with the Yshiro federation as a partnership to which the latter would contribute “traditional” forms of natural resource use.

Thus, having agreed on the goal of making hunting sustainable, the Yshiro federation and Prodechaco divided tasks: The federation would promote a series of discussion in their communities to make the goal of sustainability clear and to organize operations accordingly; Prodechaco, in turn, would arrange with the National Parks Direction the technical and legal aspect of the hunting season, which from then on began to be described as a sustainable hunting program. In the ensuing months, each party contributed their specific visions and demands into the making of the program and by the time it was launched it seemed that everybody was operating according to a common set of understandings about what the program entailed.

However, two months after the program’s beginning, Prodechaco and the inspectors sent by the National Parks Direction began asserting that Yshiro and nonindigenous hunters were actively disregarding the agreed-on regulations, thereby turning the program into “depredation” and “devastation” as they entered into private properties and Brazilian territory (Gonzales Vera 2000a). As I show later in the article, this turn of events revealed that the hunting program had been based on a misunderstanding about how to achieve the sustainability of the animal population, albeit a particular kind of misunderstanding. …

Deer, Elk, Bison Research Methods Wildlife Habitat Wildlife Management

by admin

Comments Off

Range Reference Areas and The Condition of Shrubs on Mule Deer Winter Ranges

Charles E. Kay. 2009. Range Reference Areas and The Condition of Shrubs on Mule Deer Winter Ranges. Muley Crazy Magazine. Vol 8(1):35-40.

Dr. Charles E. Kay, Ph.D. Wildlife Ecology, Utah State University, is the author/editor of Wilderness and Political Ecology: Aboriginal Influences and the Original State of Nature [here], author of Are Lightning Fires Unnatural? A Comparison of Aboriginal and Lightning Ignition Rates in the United States [here], co-author of Native American influences on the development of forest ecosystems [here], and numerous other scientific papers.

Full text:

After predator control, range management is the key to maintaining healthy populations of mule deer and other wildlife. It is not just habitat, but the condition of that habitat. For instance, how do you tell if a range is being overgrazed? One way is to establish what are called range reference areas. There are a few places that have never been grazed by livestock, such as steep-sided mesa tops, where the vegetation can be compared with nearby grazed areas. Unfortunately, there are very few places in the West that have never been grazed by livestock and there are even fewer that deer and elk cannot reach. So in most areas it is necessary for managers to create their own range reference areas by building exclosures, which they have been doing for years.

If you are working in a national park or on a winter range where livestock use is prohibited, it is a relatively simple matter to build an 8-foot tall fence around a representative plant community, such as willows, aspen, grasslands, or upland shrubs. Then by measuring the vegetation inside and outside the exclosure on permanent sampling plots over time, you can determine what, if any, impacts wildlife are having on the range. It is also important to establish permanent photopoints when the exclosure is first erected.

If on the other hand, you are working on BLM or Forest Service lands that are grazed by livestock and wildlife, the design of the exclosure is a little more complicated. One part, termed the total-exclusion plot, is still high-game fenced to exclude both livestock and wildlife, while an adjacent area, called the livestock-exclusion plot, is fenced in such a manner that livestock are excluded but mule deer and/or elk can jump the low fence and graze/browse by themselves — please see the accompanying photo. Unfenced adjoining areas are grazed by both livestock and wildlife. Thus by measuring the vegetation in all three areas — total exclusion, livestock-exclusion wildlife-only use, and joint use — you can determine, what vegetation changes, if any, are being caused by wildlife separately from those caused by livestock. The total-exclusion portion of the exclosure can also be used to tell if climatic variation, disease, or insects are causing certain plants to decline.

As you might have guessed, the latter type of range reference area is called a three-part exclosure because vegetation conditions are measured under three different grazing treatments. During the 1950’s and 1960’s when mule deer populations were at all time highs, a series of three-part exclosures were built on BLM and Forest Service allotments throughout the West. Unfortunately the Federal land management agencies have no nation-wide program to maintain those exclosures and many have fallen into disrepair, which is extremely shortsighted. Because without long-term range reference areas there is no way to determine what is happening on our public lands.

Deer, Elk, Bison Research Methods Wildlife Management Wildlife Policy

by admin

leave a comment

Caribou Numbers in the NWT — The Outfitter’s Battle

John Andre. 2007. Caribou Numbers in the NWT — The Outfitter’s Battle (PowerPoint presentation). Shoshone Wilderness Adventures, Lac de Gras, Northwest Territories, CA.

John Andre is majority stockholder in two Canadian corporations, Qaivvik, Ltd. and Caribou Pass Outfitters, Ltd.

Full PowerPoint presentation [here] (2.44MB)

Selected excerpts:

The caribou have been hunted for tens of thousands of years by the aboriginal peoples of the north. The health of the caribou herds is sacred to them, it is part of their very being. Generation after generation followed the caribou, or waited for them to come. They understood the movements of the great herds, and the cycle of feast and famine. Now, with “modern” technology, we track caribou with satellite collars, count nematodes in their droppings, and census them using fancy terms such as linear regression analysis and coefficient of variation. It is not an easy job, counting over a million animals, scattered over tens of thousands of square miles of wilderness. This presentation is not meant to degrade, in any way, the efforts of some of the wildlife biologists that have worked hard over the last 60 years, risking their lives in an unforgiving environment, with limited budgets and manpower, to study and better understand the caribou.

The Problems Begin

In late 2005, the government split the former RWED into ENR (Environment & Natural Resources) and ITI (Industry, Tourism, and Investment.) It may or may not be a coincidence, but this is when problems with the government began.

In May of 2006, we were abruptly told that we had to stop selling caribou hunts for that year; that the caribou numbers had dropped significantly. This cost the industry three months of sales, and hundreds of thousands of dollars. The question is, if the next survey hadn’t been done yet, how did the government know for sure the herds were down? Was the outcome preconceived?

In June of 2006, the Bathurst herd was surveyed, and was down to 128,000 caribou. Minister Miltenberger, of the ENR , told the outfitting industry that they were cutting our tag quotas back to the pre-2000 level of 132 tags, for the 2007 season. At the same time, resident hunters were reduced from 5 tags to 2 tags, and bulls only. (The harvest of mature bulls has consistently been shown to have zero effect on overall ungulate population growth.) The outfitting industry, although not necessarily agreeing with their numbers or science, wanted to do their part to help the caribou, and so we accepted this slashing of our industry by nearly 30%.

The fact is, we hadn’t looked at the numbers carefully enough.

A Proposal to Eliminate Redundant Terminology for Intra-Species Groups

M. A. Cronin. 2006. A Proposal to Eliminate Redundant Terminology for Intra-Species Groups. Wildlife Society Bulletin 34(1):237–241; 2006

Dr. Matthew Cronin PhD. is Research Associate Professor of Animal Genetics, School of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences, University of Alaska Fairbanks. He is also a member of the Alaska Board of Forestry.

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

Abstract

Many new terms have come into use for intra-species groups of animals defined with genetic criteria including subspecies, evolutionarily significant units, evolutionary units, management units, metapopulations, distinct population segments, populations, and subpopulations. These terms have redundant meanings and can lead to confusion for biologists, managers, and policy makers. I propose that for wildlife management we can simplify intra-species terminology and use only the terms subspecies, populations, and subpopulations. These 3 terms have roots in evolutionary and population biology and can incorporate genetic, demographic, and geographic considerations.

Recently, there has been a proliferation of terms used to describe groups of animals below the species level. For example, Wells and Richmond (1995) identified more than 30 terms used to describe groups generally referring to populations. They also discussed the problems with scientific communication associated with such extensive and redundant terminology.

The importance of intraspecies definitions is exemplified by the United States Endangered Species Act (ESA). The ESA allows listing of species, but it also allows listing of subspecies and distinct population segments (DPS) without clear definition of these terms. The importance of these intra-specific categories is evident in the large number of subspecies and DPS listed under the ESA. For example, more than 70% (57 of 81 listed taxa) of the listed mammals in the United States are identified as subspecies or DPS (http://endangered.fws.gov/wildlife.html). Examples of subspecies listed under the ESA with questionable subspecies status include the California gnatcatcher (Polioptila californica californica, Cronin 1997, Zink et al. 2000) and Preble’s meadow jumping mouse (Zapus hudsonius preblei, Ramey et al. 2005). Other examples of indefinite subspecies designations that affect management and policy are given by Cronin (1993) and Zink (2004).

The importance of clear definition of DPS has been recognized by the agencies administering the ESA (i.e., The United States Fish and Wildlife Service and National Marine Fisheries Service). These agencies noted: “Federal agencies charged with carrying out the provisions of the ESA have struggled for over a decade to develop a consistent approach for interpreting the term ‘distinct population segment’” (Waples 1991:v); and “…it is important that the term ‘distinct population segment’ beinterpreted in a clear and consistent fashion.” (Federal Register 7 Feb. 1996, Vol 61:4722). The National Research Council (NRC 1995:55) recognized the importance of identification of intraspecific units for ESA consideration and stated: “Unless we agree to preserve all endangered or threatened organisms of all taxonomic ranks, we must find ways to identify those groups of organisms we consider to be significant.

Large predators: them and us!

Dr. Valerius Geist, PhD. 2008. Large predators: them and us! Fair Chase. Vol. 23, No. 3. pp. 14-19

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

We pay close attention to large predators. We do so because we evolved as prey. It was our ancient fate to be killed and eaten, and our primary goal to escape such. Our instincts are still shaped that way.

There is thus a reason why the bloody carnage on our highways is a mere statistic, but the mauling of a person by a grizzly is news. It’s not only that so many fossilized remains of our ancient ancestors are meals consumed by large predators in secluded caves or rock niches, but also that we speciated like large herbivores. That is, our pattern and timing of forming species, of adapting to landscapes, mimics and coincides with that of deer, antelope or cattle, but not that of large carnivores. And that despite our fondness for meat, despite “man the hunter”, and despite the fact that at least one species of humans, Neanderthal man, grew into a super predator.

Large herbivores readily form new species and show a pattern of strong speciation from the equator to the poles, terminating in the cold, glaciated latitudes as “grotesque ice age giants”. Large predators do not. They evolve no grotesque ice age giants comparable to the woolly mammoths among elephants, or the massive-antlered giant deer among deer, the giant sheep, or anything else for that matter as grotesque as ourselves. Is there a more grotesque animal than man? And we did it twice, once as Neanderthal and once as Modern Man. Moreover, herbivores readily form dwarf species under poor ecological conditions such as in rainforests, deserts or predator-free oceanic islands, and they differentiate rapidly into new subspecies as they disperse geographically into new habitats. Predators form no dwarfs, on islands or otherwise. Nor do they segregate sharply into swarms of regional subspecies. Large herbivores do that - and so do humans. Also, our bursts of speciation coincide in time with those of African antelope.

Humans grow small canine teeth, not the large combat-canines typical of apes. Canine reduction is a signature of a common anti-predator adaptation, called the “selfish herd”. In such unrelated individuals cluster together in the open as protection against predation. Herbivores form “selfish herds”, predators do not. Herbivores may “evolve away” huge combat-canines, as shown not only by us, but by deer, horses, rhinos and half a dozen extinct families of large mammalian plant eaters. Carnivores reduce no canines!

Our ancient herbivore root is still reflected in our taste preferences, for when we eat meat we flavor it liberally with plant poisons (pepper, chili, sage, thyme, curry etc). Apparently meat does not really taste “good” till it tastes of “plant”! We also have the herbivore’s craving for salt. So, watch what you reach for next time you get a sizzling steak!

While we may have evolved as hunters, we did not evolve like predators. …

Deer, Elk, Bison Population Dynamics Predators Wildlife Management

by admin

7 comments

Effects of Wolf Predation on North Central Idaho Elk Populations

Idaho Department of Fish and Game, April 4, 2006, Effects of Wolf Predation on North Central Idaho Elk Populations

Full text [here] (2.3 MB)

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Gray wolves (Canis lupus) were reintroduced into Idaho in 1995 and listed as an experimental nonessential population under Section 10(j) of the Endangered Species Act (ESA). Thirty-five wolves were reintroduced and by 2005, an estimated 512 wolves (59 resident packs and 36 breeding pairs) were well distributed from the Panhandle to southeast Idaho. In February 2005, the U.S Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) modified the 10(j) rule which details State options for management of wolves impacting domestic livestock and wild ungulates (Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Regulation for Nonessential Experimental Populations of the Western Distinct Population Segment of the Gray Wolf [50 CFR Part 17]).

The provisions of the 10(j) rule fall short of allowing the states’ preferred management tool of regulated hunting. However, under Section (v): “If gray wolf predation is having an unacceptable impact on wild ungulate populations (deer, elk, moose, bighorn sheep, mountain goats, antelope, or bison) as determined by the respective State and Tribe (on reservations), the State or Tribe may lethally remove wolves in question. In order for the provision to apply, the States or Tribes must prepare a science-based document that: 1) describes what data indicate that ungulate herd is below management objectives, what data indicate there are impacts by wolf predation on the ungulate population, why wolf removal is a warranted solution to help restore the ungulate herd to State or Tribal management objectives, the level and duration of wolf removal being proposed, and how ungulate population response to wolf removal will be measured; 2) identifies possible remedies or conservation measures in addition to wolf removal; and 3) provides an opportunity for peer review and public comment on their proposal prior to submitting it to the Service for written concurrence.”

This document supports the State’s determination that gray wolf predation is having an unacceptable impact on a wild ungulate population. Specifically, this document reviews the Idaho Department of Fish and Game (IDFG) evaluation of the effect of wolf predation on an elk population below state management objectives. The document includes a review of elk population data, the cause-specific mortality research being conducted on elk, the wolf population data, and the modeling conducted to simulate impacts of wolf predation on elk using known population parameters. Additionally, this report identifies remedies and conservation measures that have already been attempted to reduce impacts of the multiple factors influencing the current elk population status, and identifies management actions and objectives to improve and monitor elk populations in the Lolo Zone.

This evaluation addresses the criteria outlined under 10J SEC. (v) and provides detailed information on the following topics:

1. What is the elk management objective?

Management objectives for elk in the Lolo Zone (Game Management Units [GMU] 10 and 12) is to maintain an elk population consisting of 6,100 – 9,100 cows and 1,300 – 1,900 bulls. Individual GMU objectives for the Lolo Zone are: 4,200 – 6,200 cows and 900 – 1,300 bulls in GMU 10; and 1,900 – 2,900 cows and 400 – 600 bulls in GMU 12. Population objectives for GMU 17 are 2,400 – 3,600 cows and 650 – 975 bulls. Objectives are based on the Department’s best estimate of elk habitat carrying capacity and acknowledge a reduction in habitat potential from the conditions observed in the 1980s. In 1989, the Department estimated 16,500 elk in the Lolo Zone. Current cow and bull objectives (7,400) are 60% of the 1989 estimate of 12,378 cow and bull elk. In 2006, the Department estimated 4,233 cow and bull elk in the Lolo Zone.

2. Data used to evaluate populations in relation to management objective.

IDFG biologists use aerial surveys to monitor elk populations throughout the state, including GMUs 10, 12, and 17. Surveys are designed to provide a statistically and biologically sound sampling framework. Biologists generate estimates (and confidence intervals) of population size, age ratios (e.g., calves:100 cows) and sex ratios (e.g., bulls:100 cows) from the survey data. Current status of elk populations are: 2,276 cows and 504 bulls in GMU 10; 978 cows and 475 bulls in GMU 12; and 2,076 cows and 486 bulls in GMU 17.

3. Data that demonstrate the impact of wolf predation.

Elk survival rates were estimated using radio-collared animals. A total of 64 adult cow elk were captured, radio-collared, and monitored in GMUs 10 and 12 in 2002-2004 (90 elk-years). Combining samples across areas and years produced point estimates of annual elk survival (includes all mortality sources) ranging from 75% to 89%, with a 3-year weighted average of 83%. More recently, survival from March 2005 through February 2006 was 77%.

Nine of 25 (36%) mortalities among adult cow elk from January 2002 through March 2006 were attributed to wolves. Wolf-caused mortality was not detected during 2002 or 2003; whereas 1 death was attributed to wolf predation in 2004 and 8 through 1 March 2006. Three additional losses resulted from predation, but species of predator could not be determined; 4 were attributed to mountain lions; and 9 were attributed to factors other than predation (e.g., hit by a vehicle, harvested, disease) or cause of death could not be determined.

Similar survival and cause-specific mortality data for elk in GMU 17 does not exist because of logistical difficulties with capture and monitoring of elk in designated Wilderness.

IDFG used the available data and assumptions based on peer-reviewed literature to simulate the impacts of wolf predation on elk populations in north-central Idaho. All simulations revealed a lack of cow elk population growth in the presence of wolf predation. Most simulations suggest moderate to steep declines in abundance caused by wolf predation. Regardless of the approach we used to model elk populations, all simulations used suggest wolves are limiting population growth.

4. Why wolf removal is warranted.

Several factors may have contributed to the elk population decline in the Lolo Zone, including harvest management, habitat issues, and predation. The Department and collaborators have aggressively addressed each of these factors for a number of years. Nevertheless, the Lolo Zone does not meet state management objectives. Without an increase in cow elk survival, the Lolo Zone elk population is unlikely to achieve management objectives.

The available data indicate that wolf predation is, at a minimum, partly additive and likely contributes to low adult female elk survival. Based on our evaluation and analysis, the State has determined that wolf predation is having an unacceptable impact on elk populations in the Lolo Zone. This evaluation demonstrates that wolves play an important role in limiting recovery of this elk population and that wolf removal is warranted as allowed under the 10(j) rule.

Management of most big game populations is accomplished through regulated harvest by hunters. A reduction in wolf numbers in the Lolo Zone would ideally be accomplished through regulated take by sportsmen rather than by state or federal agencies, and all alternatives for removal would be explored.

5. Level and duration of wolf removal.

During year one, we propose to reduce the wolf population in the Lolo Zone by no more than 43 of the estimated 58 wolves (75% reduction) that currently occupy the zone. The first year reduction represents about 8% of the estimated 512 wolves present in Idaho in 2005. The wolf population will be maintained at 25-40% of the pre-removal wolf abundance for 5 years. Concurrently, we will monitor elk and wolf populations. After 5 years, results will be analyzed and a peer-reviewed manuscript will be prepared that evaluates the effect of fewer wolves on elk population dynamics.

6. How will ungulate response be measured?

We will monitor the performance of elk populations in GMUs 10 and 12 with ongoing statewide research efforts on elk and mule deer and within the context of Clearwater Region wildlife management activities. The information will include fecundity, age/sex-specific survival rates, and cause-specific mortality rates. We will use aerial surveys to monitor elk populations in GMUs 10, 12, and 17. In GMUs 10 and 12, complete surveys will be scheduled for 2006, 2008, and 2010. In GMU 17, complete surveys will be scheduled for 2007 and 2010. Composition surveys will be flown in intervening years. In GMUs 10 and 12, we will document elk survival rates and cause-specific mortality factors from samples of radio-marked adult cow and calf elk.

Deer, Elk, Bison Population Dynamics Predators Wildlife Management Wildlife Policy

by admin

Comments Off

The Truth about Our Wildlife Managers’ Plan to Restore “Native” Ecosystems

George Dovel. 2008. The Truth about Our Wildlife Managers’ Plan to Restore “Native” Ecosystems. The Outdoorsman, Number 30, Aug-Sept 2008.

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

In 1935 when Cambridge University botanist Arthur Tansley invented the term “ecosystem” in a paper he authored, he was attempting to define the system that is formed from the relationship between each unique environment and all the living organisms it contains.

Ecologists concluded that these individual systems evolved naturally to produce an optimum balance of plants, herbivores that ate the plants, and carnivores that ate the herbivores. Many accepted this “food chain” theory as a permanent state of natural regulation and a theory was advanced that certain “key” species of plants and animals were largely responsible for maintaining these “healthy” ecosystems.

But subsequent archeological excavations or core samples of the buried layers of periods in time revealed that these “perfected” ecosystems were actually in a continuing state of change which could be caused by changes in weather, climate or various organisms. They concluded that parasites or other organisms that were not included in their food chain charts often caused radical population changes in one or more of the keystone species.

The “Balance-of-Nature” Myth Keeps Surfacing

In 1930 noted Wild Animal Ecologist Charles Elton wrote, “The ‘balance of nature’ does not exist and perhaps never has existed. The numbers of wild animals are constantly varying to a greater or less extent, and the variations are usually irregular in period and always irregular in amplitude (being ample).” Yet 33 years later, in a highly publicized Feb. 1963 National Geographic article, titled, “Wolves vs. Moose on Isle Royale,” fledgling Wolf Biologist David Mech and his mentor, Durward Allen, claimed just the opposite. …

Debunking the “Balance-of-Nature” Myth

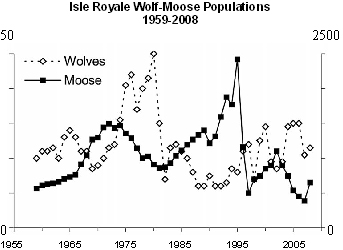

The extreme “spikes” (highs and lows) in numbers of keystone species resulting from reliance on the theory that “natural regulation” will produce a “balance” are evidence that the so-called “Balance of Nature” is a pipe dream. One fairly long-term example of this is seen in the following graph recording 50 years of wolf and moose populations on Isle Royale National Park in Michigan.

Population Dynamics Wildlife Habitat Wildlife Management Wildlife Policy

by admin

Comments Off

Yellowstone’s Destabilized Effects, Science, and Policy Conflict

Frederick H. Wagner. 2006. Yellowstone’s Destabilized Effects, Science, and Policy Conflict. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

Review by Cliff White, Parks Canada, Banff, Alberta, Ca. [first published in Mountain Research and Development Vol 28 No 2 May 2008]

In an influential book of the 1960s, Fire and Water: Scientific Heresy in the Forest Service, Ashley Schiff (1962) documented how, for over 3 decades, the United States Forest Service subverted ecological science to justify an agency policy of total fire suppression. This policy was especially flawed in southeastern pine forests that evolved under a regime of periodic burning. Schiff’s exposé showed how, in a technologically-based society, science could be systematically manipulated to become clever advocacy for a political end. The book became a must read for a generation of ecological researchers and natural resource policy specialists.

Fred Wagner, formerly associate dean of the Natural Resources department at Utah State University, continues this tradition of exceptional scholarship to describe policy-driven research in Yellowstone, the United States’ flagship national park. Ironically, the general political and ecological scenario is in many respects similar to the southeastern pine forest debacle—management actions driven by a strong political constituency were imposed on an ecosystem ill-adapted to them, and scientists were unwilling or unable to evaluate and document obviously negative outcomes. In Schiff’s example, the fire suppression program was rooted in a strong American land management and resource husbandry movement of the early 1900s. In Wagner’s work, Yellowstone’s management and scientific research is motivated by equally powerful, but opposite societal forces supporting wilderness or “natural regulation.”

For those unfamiliar with the Yellowstone situation, removal of native peoples from the park in the 1800s and reduction in large carnivores in the early 1900s provided favorable conditions for the population of elk (Cervus elaphus), a generalist herbivore, to increase dramatically. After government biologists observed the effects of high densities of elk on soil and vegetation in the 1920s, park rangers routinely culled the herd for over 4 decades. In the 1960s, recreational game hunters lobbied to take over the cull. Given the potential political incompatibility of sport hunting with conservation in one of the world’s premier national parks, the federal government made the decision to cease elk culling. Park managers and senior scientists then carefully selected a generation of researchers to evaluate the revised policy. The result was a new paradigm of “natural regulation” that was underlain by 4 key hypotheses:

1) long-term human hunting, gathering and burning had not substantially influenced the ecosystems of North America’s Rocky Mountains;

2) ungulate populations in Yellowstone were, over the long term, generally high;

3) carnivore predation was a “non-essential adjunct” having minimal influence on elk numbers; and

4) high elk numbers would not cause major changes in plant communities, ungulate guilds, and other long-term ecosystem states and processes.

Although the natural regulation paradigm seems rather farfetched today, remember that it was born in the 1960s, a time of antiestablishment flower children, when wilderness was untrammeled by Native Americans, when biologist and author Farley Mowat’s wolves subsisted on mice (Mowat 1963), and the only “good fires” were caused by lightning. Moreover, an excellent argument can be made that ecological science needs large “control ecosystems” with minimal

human influences.

In the 40 or so years since the implementation of the national regulation policy, both the National Park Service and outside institutions conducted many ecological studies. These culminated in 1997 with a congressionally mandated review by the National Research Council. It is this wealth of research and documentation that Fred Wagner uses to evaluate changes over time in the Yellowstone ecosystem. He provides meticulous summaries of research in chapters on each of several different vegetation communities, the ungulate guild, riparian systems, soil erosion dynamics, bioenergetics, biogeochemistry and syntheses for the “weight of evidence” on the primary drivers of ecological change. This background allows readers to develop their own understanding on the results of this textbook case of applied ecological science.

Wagner clearly shows that most studies did not support the hypotheses of natural regulation. In cases where studies did seem to support a hypothesis, methods and results were suspect. The elk population clearly grew beyond predictions, some plants and animals began to disappear, and the importance of Yellowstone’s lost predators and Native Americans should have become undeniable. However, faced with these incongruities, park managers still supported the natural regulation policy. Some researchers closely affiliated with management then began to invoke climate change as a potential factor for observed ecosystem degradation, but the evidence for this was similarly tenuous. On the basis of the almost overwhelming evidence, Wagner concludes that much of the park-sponsored science on the natural regulation paradigm “missed the mark” and that “Yellowstone has been badly served by science.”

For scientists or managers working in similar arenas of high ecosystem values and intense politics, the book’s concluding chapters will be of most interest. Here, Wagner explores the interface between science and policy. As an alternate model to Yellowstone’s research and management system, he promotes an adaptive management process (Walters 1986) where an open political environment exists between scientists, stakeholders, and managers. Here, a controversial management option such as natural regulation could have been evaluated, as Wagner advises, “in the bright light of objective scientific understanding.” Stakeholders and managers could then use this knowledge as a basis to adjust policies quickly before grave ecological consequences occur.

However, the limited and, in terms of literature review, dated discussion of the public policy process is a weakness of the book. A more complete discussion of ecosystem management in a highly polarized political environment could have described a range of current approaches for collaborative problem solving. In fact, another recent review of wildlife management in Yellowstone concluded that the major problem facing the park was not the quantity or quality of the science, but the lack of mechanism to resolve conflicts between and within groups of scientists, stakeholders and agency managers. Gates et al (2005) remark that “collaboration is necessary to define what is acceptable; science is necessary to define what is possible; organizing people to use knowledge to design and implement management in the face of uncertainty is fundamental.” Applied ecological researchers, progressive managers, and stakeholders with a strong civic responsibility should strive for this ideal. Our parks, and indeed most places on our planet, need high-profile models such as Yellowstone, where science should help people to understand, value, and maintain the biodiversity of ecosystems.

REFERENCES

Gates CC, Stelfox B, Muhley T, Chowns T, Hudson RJ. 2005. The Ecology of Bison Movements and Distribution in and beyond Yellowstone National Park. Calgary, Canada: Faculty of Environmental Design, University of Calgary.

Mowat F. 1963. Never Cry Wolf. Toronto, Canada: McClelland and Stewart.

Schiff AL. 1962. Fire and Water: Scientific Heresy in the Forest Service. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Walters C. 1986. Adaptive Management of Renewable Resources. New York: Macmillan.