Deer, Elk, Bison Population Dynamics Predators Wildlife Management Wildlife Policy

by admin

The Truth about Our Wildlife Managers’ Plan to Restore “Native” Ecosystems

George Dovel. 2008. The Truth about Our Wildlife Managers’ Plan to Restore “Native” Ecosystems. The Outdoorsman, Number 30, Aug-Sept 2008.

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

In 1935 when Cambridge University botanist Arthur Tansley invented the term “ecosystem” in a paper he authored, he was attempting to define the system that is formed from the relationship between each unique environment and all the living organisms it contains.

Ecologists concluded that these individual systems evolved naturally to produce an optimum balance of plants, herbivores that ate the plants, and carnivores that ate the herbivores. Many accepted this “food chain” theory as a permanent state of natural regulation and a theory was advanced that certain “key” species of plants and animals were largely responsible for maintaining these “healthy” ecosystems.

But subsequent archeological excavations or core samples of the buried layers of periods in time revealed that these “perfected” ecosystems were actually in a continuing state of change which could be caused by changes in weather, climate or various organisms. They concluded that parasites or other organisms that were not included in their food chain charts often caused radical population changes in one or more of the keystone species.

The “Balance-of-Nature” Myth Keeps Surfacing

In 1930 noted Wild Animal Ecologist Charles Elton wrote, “The ‘balance of nature’ does not exist and perhaps never has existed. The numbers of wild animals are constantly varying to a greater or less extent, and the variations are usually irregular in period and always irregular in amplitude (being ample).” Yet 33 years later, in a highly publicized Feb. 1963 National Geographic article, titled, “Wolves vs. Moose on Isle Royale,” fledgling Wolf Biologist David Mech and his mentor, Durward Allen, claimed just the opposite. …

Debunking the “Balance-of-Nature” Myth

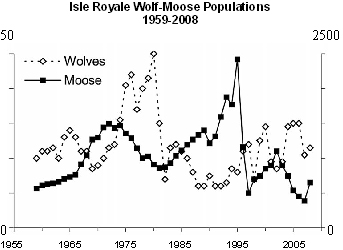

The extreme “spikes” (highs and lows) in numbers of keystone species resulting from reliance on the theory that “natural regulation” will produce a “balance” are evidence that the so-called “Balance of Nature” is a pipe dream. One fairly long-term example of this is seen in the following graph recording 50 years of wolf and moose populations on Isle Royale National Park in Michigan.

When the island’s wolves were first counted from the air by David Mech in 1959 he estimated there were ~20 wolves and fewer than 600 moose – a ratio of less than 30 moose per wolf. Aerial census flights of wolves conducted by Mech during the following three winters, and calculated moose numbers approved by his professor, Durward Allen, reflected a stable moose population and a wolf population that was increasing slightly. …

Four estimates of moose numbers covering only a three-year period were the major proof offered by Mech and Allen when they told the world that wolves cull the aged, weak and diseased moose and keep them in balance with their food supply. If they had waited four more years they would have seen the accelerating wolf population crash and the moose population more than double.

According to Park Service records, a small group of wolves appeared on Isle Royale following the 1948-49 winter. Whether they were transplanted as some biologists had recommended – or traveled to the island from Canada over a temporary ice bridge as some later speculated – they began to eat moose and breed.

When Mech began the study in 1958-59, wolves had already significantly reduced the moose population and the ratio of moose to wolves was declining below a healthy level. By 1965, there were only about 26 moose per wolf and wolf numbers declined by about 40% in the next four years.

This resulted in the moose herd doubling, but a series of severe winters in the early ’70s made the moose more vulnerable and the wolves began killing far more moose than they could eat. The wolves increased rapidly to five packs totaling 50 wolves in 1980, their highest level ever, and the moose, of course, steadily declined.

Then from 1980-82 the wolves were infected with parvovirus and the population crashed to its lowest level since the study began. Even after the parvovirus ran its course the wolf population did not recover for another 14 years until moose numbers increased to 2,400 in 1995 and then crashed the following winter.

There were only 15 wolves in January 1995 but that number had increased by >40% in January 1996. In his March 1996 Annual Report, Rolph Peterson said the 1995-96 winter was the worst on record and the combination of deep snow and moose weakened by massive tick infestations allowed the wolves to kill three times as many moose daily as occurred in a normal year. …

Mech Denounces “Balance-of-Nature”

In “How delicate is the balance of nature?” (National Wildlife 23(1):54-59) David Mech admitted that his brief research at Isle Royale as a graduate student “helped fix the balance-of-nature idea in the public mind.” But he also wrote, “During two decades of wolf research in northern Minnesota and on Isle Royale in Michigan, I have learned that far from always being ‘balanced,’ ratios of wolves and prey animals can fluctuate wildly – and sometimes catastrophically.”

Mech cited a well-controlled experiment in central Alaska where removing up to 60% of the wolves resulted in a two to four-fold increase in moose and caribou populations. He explained that these populations remained much higher than in adjacent areas with no control and said the non-hunting public should be made aware of the need to control wolves when prey populations decline.

Mech also described how protected wolves had destroyed the once famous white-tailed deer herd in northeast Minnesota during severe winters in the 1960s while he studied them. When the wolves ran out of deer in that area and turned to killing moose, Minnesota authorities closed the entire state to deer hunting in 1971. …

Allen Ignored Research – Promoted Myth

Yet despite these and other long-term predator-prey studies during the late 1960s and 70s that disproved Durward Allen’s “balance-of-nature” theory, he continued to promote the myth. His 1979 book about the wolves of Isle Royale, “Wolves of Minong:Their Vital Role in a Wild Community,” disguised the stark reality of the Isle Royale ecosystem with flowery phrases, including the following:

“The great carnivore removes the elders, the ailing, the afflicted – and also, no doubt the foolish and incompetent. For the moose it is a health, welfare, and eugenic program of inscrutable realism. The wolf manages his livestock as any husbandman must manage to survive. He is inspector of the herd, liberator of the weak, and guardian of the range. …

Even John Vucetich, who insists that Isle Royale’s ecosystem is “in balance” and “will still be ‘in balance’ even if the wolves disappear,” states “It’s just as wrong to make them (wolves) a symbol of all that’s good – some mysterious icon of the wilderness” (as it was to make them a symbol of evil) (4-20-08 AP article).

Yet Allen spent the latter part of his career promoting creation and protection of man-made wilderness ecosystems where nature could take its course – while severely limiting both human populations and the impact of humans. He joined and worked with organizations that shared his philosophy (e.g. The Wilderness Society, National Wildlife Federation, National Audubon Society, and The Nature Conservancy [TNC]).

Before his death, Allen lived to see his philosophy promoted by TNC and federal and state game agencies for nearly two decades, embodied in the Wildlands Initiative, and adopted in the 1992 U.N Biodiversity Treaty.

Isle Royale – Now Unhealthy for Mammals

Archeologists and historians tell us that Isle Royale was inhabited by humans for all or part of the year during the past 4,000 years. Yet since the introduction of the two so-called “keystone” species” and conversion to a quasi-wilderness, the forage has declined, coyotes have been driven to extinction and river otters are reportedly the only mid-sized mammals that have not either disappeared entirely or been reduced to unhealthy numbers.

Since wolves first appeared on Isle Royale, the two keystone species have existed between extremes of starvation, which invite parasites, diseases and viruses to weaken and destroy them. Unless the wolves are nearly exterminated as happened during the 1980s, Moose recruitment* remains too low to restore populations that crash due to extreme winters and surplus killing by wolves.

Surprising Admissions by Wolf Experts

In a 2003 paper entitled, “Yellowstone After Wolves,” Douglas Smith, Rolph Peterson and Douglas Houston admitted their predictions were often wrong:

“Although our expectations for wolf effects in Yellowstone are based on inferences from other studies, and may seem self-evident, we realize that specific predictions may be wrong. Even in a system as simple as Isle Royale, predictability has been poor following four decades of scientific scrutiny; none of the expectations for the moose herd, voiced in turn by Mech (1966), and Peterson (1977) actually happened.

“Rather, external forces such as severe winters, summer heat and outbreaks of winter ticks (driven by warm, dry spring weather) have caused the moose population to decline (DelGiudice et al. 1997). Surprises, as in the arrival of exotic disease which caused a wolf crash at Isle Royale in the early 1980s, are virtually guaranteed in the long term, and they will assuredly influence, and possibly determine the outcome of the great natural experiment in wolf-elk dynamics now launched at Yellowstone.

“Large perturbations, as with unique weather-driven events, will loom large in the future of Yellowstone. The 1988 fires burned about 36% of the land area of the park, affecting forage supplies for native ungulates (positively and negatively), but there is plenty of room for future fires in a climate that seems more conducive to large conflagrations. Given time, the severe winter of 1996-1997 will be matched and exceeded.”

“Some curtailment of midwinter shooting of cow elk outside the park might be necessary because wolves and humans, with very different hunting strategies, nevertheless compete over common prey. Successful coexistence of wolves and human hunters is a management conundrum that will test wildlife managers and challenge long-held beliefs.”

The biologists’ suggestion that “some curtailment of cow elk hunting outside the park might be necessary” ignored the reality that wolves will continue to multiply as long as any food source is available. Despite a temporary reduction in YNP wolf numbers resulting from parvovirus and sarcoptic mange, and a reduction in antlerless elk hunting permits from 2,880 to only 100, the Northern Herd elk count continues to decline. …

Decline of the Central YNP Elk Herd

Local citizens who have suffered substantial economic loss as a result of the declining Northern elk herd continue to carefully monitor and publicize the decline. But few people are aware of the severe decline in the Central YNP herd – the only elk that are never hunted and spend their entire lives inside the Park.

From 1958-1994 that herd varied from about 400 to 800 elk with an early winter count in 1994 totaling about 750 animals. …

In the 2003 “Yellowstone After Wolves” article, the wolf biologists reported that the Central herd (referred to as the “Madison-Firehole Elk”) was “relatively stable” after wolf reintroduction, with a population of 500 elk. (It had actually declined by one-fourth in the two years since 2001 when local wolf numbers doubled.)

From 1996-2008 the Central elk herd declined by 73% to a historical record low of only 200. Because that herd exists entirely on public land with no hunting and has remained at a low density with small group sizes and intermittent wolf activity, none of the biologists’ stock excuses can be used to explain away the 73% reduction in the elk population since wolves were introduced.

The Results of Natural Regulation in YNP

From 1967 until wolves were released in the Park in 1996, YNP officials relied on “natural regulation” to reduce elk populations and reverse decades of habitat damage. Instead, elk populations in both the Northern Herd and the Central Herd steadily increased for the next three decades despite increased damage to YNP forage.

In the absence of top carnivores or other controls such as regulated hunting, large herbivores, including elk and moose, will continue to multiply until they outgrow the ability of vegetation to provide adequate nutrition (exceed carrying capacity). When this continues, despite natural controls that “kick in” with both herbivores and their forage, the animals are described as “density dependent.”

When top carnivores such as wolves are added to halt the inevitable long-term damage to the ecosystem, the ultimate result (unless predator density is carefully controlled) is depleted prey populations that remain well below the carrying capacity of their range. Once the predators also deplete their alternate food sources, they succumb to starvation, disease and killing each other. …

Origin of the YNP Natural Regulation Theory

Four years after YNP adopted a policy of letting nature “manage” the elk and buffalo in 1967, biologist Douglas Houston presented a new hypothesis (untested theory) that Northern YNP elk would limit their own numbers (without human intervention) by competing with each other for grazing combined with unfavorable winter weather (”bottom-up” regulation). Houston also said this would occur without a significant impact to the vegetation or to other animals that also utilized that vegetation.

Despite Houston’s predictions, the Northern elk herd, which totaled only 3,167 animals in 1968, increased steadily along with the severe decline in riparian area forage and quaking aspen stands inside the Park. Yet questionable “studies” blamed these declines on long-term changes in climate and weather patterns.

A 1982 book by Houston claiming that “Natural Regulation” had produced a healthy natural ecosystem received “Outstanding Book of the Year” honors from The Wildlife Society (TWS). Like Mech’s and Allen’s earlier “Balance-of-Nature” claim in National Geographic, this and other publications by Houston prompted widespread acceptance of the flawed theory of “Natural Regulation” by wildlife managers worldwide.

It assured acceptance of the UN/TNC “Wildlands” agenda by wildlife managers, and paved the way for the ecological slums they are promoting today by managing only people rather than wildlife. However a number of wildlife ecologists disagreed with the theory and conducted definitive research to verify what actually happened during the 126-year recorded history of Yellowstone.

Kay: “Natural Regulation is a Failed Hypothesis”

Foremost among these were Utah State University Researchers Dr. Charles Kay and his former professor, Dr. Frederick Wagner. As chairman of a committee that spent five years reviewing wildlife management in our National Parks, Wagner was the lead author of Wildlife Policies in the U S National Parks (1995).

The book discussed the decline in species biodiversity and addressed various misconceptions and ambiguities of such concepts as “Natural Regulation,” “Carrying Capacity,” and the term “Natural.” Meanwhile Dr. Kay published, Yellowstone: Ecological Malpractice, in which he concluded:

“Natural regulation is a failed ecological hypothesis that must be rejected as a valid scientific interpretation of the real world. The simple truth is that ungulate populations will not internally self-regulate before having had a serious impact on vegetation.”

The “before and after” photographs in his book spanning a century of YNP forage decline were presented to a public lands oversight hearing in Congress in February of 1997. Dr. Kay provided examples of Park officials altering information to cover up the failure of its natural regulation policy and testified that Interior employees had tried to get him fired from the university and from research he was doing for Parks Canada after he published an independent analysis of their wolf recovery proposal.

Humans Shaped Intermountain Ecosystems

He also testified that there was no evidence of elk or bison overgrazing Yellowstone prior to it becoming a national park because hunting by Native Americans kept ungulate numbers low, which promoted biodiversity. In his research, Kay has repeatedly emphasized that Native Americans were the real keystone species and top-of-the-food chain predators in YNP and elsewhere in the West.

Their burning practices and harvest of large ungulates for thousands of years shaped the ecosystems in Yellowstone and the Intermountain West. Kay concluded his testimony with the following comment:

“Based on what I know about ‘natural regulation’ management, if I wanted to protect an area, the last thing I would do would be to make it a national park and the next to the last thing I would do would be to turn it into a wilderness area.”

Wagner Receives “Outstanding Book” Award

In 1999, 32 years after the natural regulation policy was adopted, YNP biologists claimed they needed more years of research in order to test the natural regulation hypothesis. But Dr. Wagner told the National Research Council they had a 126-year data-set of interaction between YNP ungulates and their ecosystem and half a century of research which should be adequate to determine if the elk herd had reached equilibrium.

In August 2008, TWS announced that Dr. Wagner would receive its “2008 Wildlife Publication Award – Outstanding Book” for his 2006 book Yellowstone’s Destabilized Ecosystem: Elk Effects, Science and Policy Conflict. His book documents extreme fluctuations in the Northern Elk Herd and is highly critical of Park Service management.

“In 1967 the NPS introduced a ‘Nature Knows Best’ approach and stopped controlling the size of the (elk) herd,” he wrote. “A new contingent of NPS research biologists disputed earlier scientific evidence and claims about best management practices of elk and other wildlife in the park. In the process, they totally negated everything that had been observed, recorded and published for nearly a century.”

Dr. Kay pointed out that TWS gave Douglas Houston the same prestigious award for promoting his flawed natural regulation theory in the early 1980s as it gave Dr. Wagner in 2008 for disproving Houston’s hypothesis. He asks, “Are we supposed to believe that Yellowstone is an ecological slum – or that it’s the epitome of land management as claimed by Park officials and the “greens” who want to depopulate half of the U.S. so that nature can take its course?”