Of Fates, Forests, and Futures: Myths, Epistemes, and Policy in Tropical Conservation

Susanna B. Hecht. 1993. Of Fates, Forests, and Futures: Myths, Epistemes, and Policy in Tropical Conservation. Horace Marden Albright Lecturer in Conservation. UC Berkeley College of Natural Resources

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts

Introduction

In spite of increasingly strident international censure, the global rates of deforestation in the tropical world have more than doubled during the last decade (Myers 1990). This destructive pattern is well advanced in the Western Amazon. In 1980, less than 8,000 km of Rondonia’s forests had fallen. Acre’s forests were largely intact. By the end of the decade some 60,000 km, or 17% of the state of Rondonia had been cleared. In Acre - more distant, fewer roads and more politically organized - by the mid-1990s, some 5% of the lands had been deforested (FUNTAC 1990). Spurred by government colonization programs, fiscal distortions, land speculation, timber concessions, dubious land titles and the migration of almost a million peasants from southern Brazil (World Bank, 1989), forests relentlessly fell. Degraded pastures and abandoned farms soon replaced rich woodlands. Weed invasion, declines in soil fertility, and frontier economics all took their toll as colonists and ranchers pressed ever forward. …

Rapid deforestation and resource degradation are related to the ecological instability and economic peculiarities of the forms of land occupation expressed by current regional development efforts. But why such forms of land use have come to dominate the landscape leads us further to questions that lie at the heart of deforestation: how we understand it, and how we hope to halt it.

What I will do in this article is to explore some of the deeper epistemological issues that inform our models and environmental sciences of how the world unfolds in these regions. While the scientific literature, airwaves and popular culture barrage us with “explanations,” these competing, largely unexamined paradigms have policy and real-world outcomes. I will examine first two broad overarching approaches that have been instrumental in defining resources debates in the first world, how these have articulated with the scientific frameworks that have been significant in interpreting tropical forests and populations as well as their peoples. I will also discuss the emerging counter view. These will then be linked to explanations of deforestation, and their policy consequences.

The Amazon has always been a mirror to the vibrant fantasies of its observers. Any review of its history is always tremendously disconcerting because there are so many disparate versions of Amazonia, in part because the region is so enormous. But as much as it is a forest of trees, it is also in Turner’s phrase “a forest of symbols.” …

Cultivated Landscapes of Native Amazonia and the Andes

William M. Denevan. 2001. Cultivated Landscapes of Native Amazonia and the Andes. Oxford University Press, 2001.

Review by Mike Dubrasich

Cultivated Landscapes of Native Amazonia and the Andes is widely recognized as the modern masterpiece of historical landscape geography. It is one of a trilogy of books inspired and coordinated by William Denevan. The others are Cultivated Landscapes of Native North America by William Doolittle and Cultivated Landscapes of Middle America on the Eve of Conquest by Thomas M. Whitmore and B.L. Turner II.

The authors of all three volumes are landscape geographers who have studied the profound and lasting impacts that indigenous human beings have had over thousands of years on the vegetation, soils, hydrology, and wildlife of the Americas.

Denevan is the unofficial “godfather” of an intellectual tradition that developed under Carl O. Sauer in the Department of Geography at Berkeley. UCLA’s Susanna Hecht described that tradition (tongue in cheek, with affection) as a machine:

The geographer William Denevan’s “machine” (and its affines) and the Berkeley School of cultural geography converged with historical ethnobotany and compiled an extensive set of analyses on indigenous resource management systems in Central America, the Andes, and the Amazon, where questions about landscape and ecological histories whose logics, though not divorced from productionist questions (what fed large populations in these difficult montane or tropical environments?) were linked to their historical, agroecological and environmental underpinnings (Balée and Erickson 2006; Denevan 1970, 1976, 1992, 2001; Denevan and Padoch 1987; Erickson 2000; Whitmore and Turner 2001; Zimmerer 2001). It was this framework, as well as pro indigenous activism that gave impetus to other projects, such as Darrell Posey’s 12 year Kayapó project, and those spearheaded by New York Botanical Garden’s Gillian Prance. — from SB Hecht, Chapter 7, Kayapó Savanna Management: Fire, Soils, and Forest Islands in a Threatened Biome in William Woods et al. 2009. Amazonian Dark Earths: Wim Sombroek’s Vision, Springer (soon to be released).

All those mentioned by the verbose Hecht (Bill Woods, Bill Balée, Clark Erickson, etc.) and many more of our leading landscape geographers, anthropologists, ethnobotanists, and forest historians, trace their intellectual roots to Bill Denevan. Charles C. Mann’s fascinating bestseller, 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus [here], was inspired directly and indirectly by Denevan and his “machine”.

In a biographical essay about Bill Denevan, I described him (tongue in cheek, with affection) as “the real Indiana Jones” [here]. As an adventurous young man in the 1950’s, Denevan boarded a freighter in Los Angeles and then jumped ship in Lima, Peru. He subsequently traversed South America and in a flight over eastern Bolivia “discovered” the signs of a lost civilization in the Llanos de Mojos. And like the fictitious Indiana Jones, Denevan went on to became a scholar (and Chair, now emeritus, of the Dept. of Geography at the University of Wisconsin-Madison).

Cultivated Landscapes of Native Amazonia and the Andes (and it’s companion books) is the culmination of a lifetime of pathfinding research and teaching. It is a text, organized and written for graduate and undergraduate instruction, but between the lines it is also a tale of adventure and exploration. The insights related in Cultivated Landscapes were gained by the combined efforts of dozens of field researchers braving jungles, savannas, trackless swamps, towering mountains, and seared deserts. The book is a synthesis, but it represents hands-on fieldwork in what we think of today as wilderness, but what in truth has been home to humanity for 10,000 years or more.

Native Americans as active and passive promoters of mast and fruit trees in the eastern USA

Marc D. Abrams, Gregory J. Nowacki. 2008. Native Americans as active and passive promoters of mast and fruit trees in the eastern USA. The Holocene, Vol. 18, No. 7, 1123-1137 (2008)

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

Abstract

We reviewed literature in the fields of anthropology, archaeology, ethnobotany, palynology and ecology to try to determine the impacts of Native Americans as active and passive promoters of mast (nuts and acorns) and fruit trees prior to European settlement. Mast was a critical resource for carbohydrates and fat calories and at least 30 tree species and genera were used in the diet of Native Americans, the most important being oak (Quercus), hickory (Carya) and chestnut (Castanea), which dominated much of the eastern forest, and walnut (Juglans) to a lesser extent. Fleshy tree fruits were most accessible in human-disturbed landscapes, and at least 20 fruit- and berry-producing trees were commonly utilized by Native Americans. They regularly used fire and tree girdling as management tools for a multitude of purposes, including land clearing, promotion of favoured mast and fruit trees, vegetation control and pasturage for big-game animals. This latter point also applies to the vast fire-maintained prairie region further west. Native Americans were a much more important ignition source than lightning throughout the eastern USA, except for the extreme Southeast. First-hand accounts often mention mast and fruit trees or orchards in the immediate vicinity of Native American villages and suggest that these trees existed as a direct result of Indian management, including cultivation and planting. We conclude that Native American land-use practices not only had a profound effect on promoting mast and fruit trees but also on the entire historical development of the eastern oak and pine forests, savannas and tall-grass prairies. Although significant climatic change occurred during the Holocene, including the `Mediaeval Warming Period’ and the `Little Ice Age’, we attribute the multimillennia domination of the eastern biome by prairie grasses, berry-producing shrubs and/or mast trees primarily to regular burning and other forms of management by Indians to meet their gastronomic needs. Otherwise, drier prairie and open woodlands would have converted to closed-canopy forests and more mesic mast trees would have succeeded to more shade-tolerant, fire-sensitive trees that are a significantly inferior dietary resource.

Introduction

… Several researchers have concluded that climate is the primary driver of vegetation change in the eastern USA (Parshall and Foster, 2002; Shuman et al., 2004). While we agree with the importance of climate, we also believe that the impact and extent of early Native American land use in shaping vegetation types is more substantial than previously thought. The large disparity in presettlement vegetation expression between climax forests (set by climatic controls) and that of shade-intolerant, disturbance based vegetation types strongly points toward human intervention (Stewart, 2002; Nowacki and Abrams, 2008). Indeed, vegetation modification by Native American burning and agricultural land clearance has been particularly well documented (Cronan, 1983; Pyne, 1983; Williams, 1989; Whitney, 1994; Bonnickson, 2000).

For example, forests dominated by oak, chestnut, hickory and pine prior to European settlement are thought to require periodic fire for continued recruitment and long-term success (Abrams, 1992; Lorimer, 2001). Bromley (1935) concluded that Native American populations in southern New England were of sufficient size to burn most of the landscape on a recurring and systematic basis. Indians regularly used broadcast burning to clear forest undergrowth, prepare croplands, facilitate travel, reduce vermin and weeds, increase mast production and improve hunting opportunities by stimulating forage and driving or encircling game (Whitney, 1994; Stewart, 2002; Williams, 2002). Accidental wildfires also occurred from escaped camp and signal fires and burned into the surrounding forests. Once fires were set, there was little incentive or means by which to put them out (Stewart, 2002).

During the latter part of the Holocene, Native Americans planted a wide variety of crop species in well-managed agricultural fields adjacent to their villages (Trigger, 1978; Fogelson, 2004). MacDougall (2003) lists a total of 35 herbaceous plant species cultivated by eastern Native Americans. By the sixteenth century, the most abundant crops were maize, beans and squash, known as the ‘Three Sisters’ when planted together (Martinez, 2007). In contrast to our understanding of Native American use of fire and the cultivation of crops, we know very little about their direct and indirect impacts on the distribution of the mast and fruit trees that were important in their seasonal diet. If Native Americans had the skills to develop sophisticated systems of agriculture, did they possess similar skills to manage forests?

The promotion of mast and fruit trees would have involved active silviculture and horticulture such as reducing competing vegetation via girdling, cutting or prescribed fire and the planting and tending of beneficial tree species, possibly even creating fruit or mast orchards (Delcourt and Delcourt, 2004). The passive promotion of certain trees could have stemmed from various land uses intended for other purposes, such as broadcast fire for reducing undergrowth for security and travel, game management and general land clearance. It also could have resulted from village and agricultural field abandonment. Important mast trees used by Native Americans in the eastern USA included oak, hickory, beech (Fagus), chestnut and walnut (Juglans), species that dominated many presettlement forests. Prairies dominated much of the Central Plains and Midwest prior to European settlement, also as result of Indian burning (Sauer, 1975; Stewart, 2002). Prairie sustained huge populations of large ungulate species of Bison, deer (Odocoileus) and elk (Cervus) that were vital to the Indian diet. In any given part of the eastern USA, various vegetation types or stages may exist depending on the climate, site conditions, disturbance regime and successional status. It is important to know to what extent the dominance of mast trees and prairie were a result of Native American land use and disturbance, whether either directly or indirectly, and to what extent these were created and maintained to meet dietary needs.

The purpose of this paper is to explore the role of Native Americans in the active and passive promotion of dietary mast and fruit trees and prairie in the eastern USA, and to determine to what extent their practices shaped the overall vegetation prior to European settlement. We explore the hypothesis that Native American land-use management was focused on the creation of large expanses of specific forest and prairie to meet their dietary needs. This will be accomplished by:

(1) synthesizing palaeoecological information on the long-term vegetation dynamics and climate during the latter part of the Holocene;

(2) comparing Native American ignitions to natural (lightning) sources;

(3) exploring ethnobotany and anthropology studies on the dietary uses of mast and fruit trees by Native Americans;

(4) reconstructing vegetation composition at the time of European settlement and ascertaining to what extent it was a result of Native American activities;

(5) documenting Native American land-use and vegetation management that has played a direct (active) or indirect (passive) role in promoting dietary mast and fruit trees in the USA. …

Selected References

Bonnicksen, T.M. 2000: America’s ancient forests. John Wiley and Sons, 594 pp.

Bonnicksen, T.M., Anderson, M.K., Lewis, H.T., Kay, C.E. and Knudson, R. 2000: American Indian influences on the development of forest ecosystems. In Johnson, N.C., Malk, A.J., Sexton, W.T. and Szaro, R., editors, Ecological stewardship: a common reference for ecosystem management. Elsevier Science Ltd, 67 pp.

Day, G.M. 1953: The Indian as an ecological factor. Ecology 34, 329–46.

Delcourt, P.A. and Delcourt, H.R. 2004: Prehistoric native Americans and ecological change. Cambridge University Press, 203 pp.

Doolittle, W.E. 1992: Agriculture in North America on the eve of contact: a reassessment. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 82, 386–401.

Guyette, R.P., Muzika, R.M. and Dey, D.C. 2002: Dynamics of an anthropogenic fire regime. Ecosystems 5, 472–86.

Kay, C.E. 2000: Native burning in western North America: implications for hardwood forest management. In Yaussy, D.A., compiler, Proceedings: workshop on fire, people, and the central hardwoods landscape; 2000 March 12–14, Richmond, KY. USDA Forest Service General Technical Report NE-274, 19–27.

Kay, C.E. 2007: Are lightning fires unnatural? A comparison of Aboriginal and lightning ignition rates in the United States. In Masters, R.E. and Galley, K.E.M., editors, Proceedings of the 23rd Tall Timbers fire ecology conference: fire in grassland and shrubland ecosystems. Tall Timbers Research Station, 16–28.

Lewis, H.T. 1993: Patterns of Indian burning in California: ecology and ethnohistory. In Blackburn, T.C. and Anderson, K., editors, Before the wilderness: environmental management by Native Californians. Ballena Press, 55–116.

Lewis, H.T. and Anderson, M.K. 2002: Introduction. In Lewis, H.T. and Anderson, M.K., editors, Forgotten fires: Native Americans and the transient wilderness. University of Oklahoma Press, 3–16.

Mann, C.C. 2005: 1491. Vintage Books.

Pielou, E.C. 1991: After the Ice Age: the return of life to glaciated North America. University of Chicago Press.

Pyne, S.J. 1983: Indian fires. Natural History 2, 6–11.

Pyne, S.J. 2001: The fires this time, and next. Science 294, 1005–1006.

Raup, H.M. 1937: Recent changes of climate and vegetation in southern New England and adjacent New York. Journal of the Arnold Arboretum 18, 79–117.

Sauer, C.O. 1975:Man’s dominance by use of fire. Geoscience and Man 10, 1–13.

Stewart, O.C. 2002: The effects of burning of grasslands and forests by aborigines the world over. In Lewis, H.T. and Anderson, M.K., editors, Forgotten fires: Native Americans and the transient wilderness. University of Oklahoma Press, 67–338.

Williams, G.W. 2002: Aboriginal use of fire: are there any ‘natural’ plant communities? In Kay, C.E. and Simmons, R.T., editors, Wilderness and political ecology: Aboriginal land management – myths and reality. University of Utah Press, 48 pp.

History of the Jarbidge, Nevada, Area

St. Louis, Bob. 2008. History of the Jarbidge, Nevada, Area With Special Emphasis on Matters Pertaining to the South Canyon Section of Jarbidge Road. Western Institute for Study of the Environment

I. Introduction

For almost one hundred years, the Jarbidge area has been the center of numerous controversies. At the turn of the century, the issue was federal protection for interests of local ranchers and other inhabitants against a wave of invading sheepmen. After gold was discovered in the area, the issue became one of local miners petitioning the federal government for a townsite. Later on, part of the area was set aside as Nevada’s first designated wilderness. Subsequently, the Forest Service set upon a crusade to expand that wilderness, in spite of local residents’ objections. Still later, the Jarbidge Wilderness was expanded after the Forest Service unilaterally closed a segment of South Canyon Road. In most recent times, Jarbidge townspeople had to appeal to Congress in order to remove Forest Service authority over their cemetery. The latest controversy returns to an earlier issue: the Forest Service once again attempted to create a de facto wilderness by closing another segment of South Canyon Road.

The following chronicle documents the history of the South Canyon of the Jarbidge River, from the perspective of the on and off relationship between the federal government and the local residents. It is not intended to be a thorough study of the history of this part of Nevada, but rather a detailed introduction into how the role of the federal government has been transformed from the “government of the people, by the people” to a self-serving entity that disregards the interests, and laws, of the local citizenry.

Ancient Earthmovers Of the Amazon

Charles C. Mann. 2008. Ancient Earthmovers Of the Amazon. Science, Vol 321, 29 August 2008, pp 1148-1152

Full text [here]

Much of the environmental movement is animated, consciously or not, by what geographer William Denevan calls “the pristine myth”—the belief that the Americas in 1491 were an almost untouched, even Edenic land, “untrammeled by man,” in the words of the Wilderness Act of 1964, a U.S. law that is one of the founding documents of the global environmental movement. - Charles C. Mann, 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus.

The most “pristine” wilderness in the America’s is widely thought to be the Amazon. But in fact the Amazon has been home to humanity and human civilization for thousands of years. New anthropological and landscape geography research has turned up yet another “lost” civilization in the supposedly untrammeled Amazon, further proof that our landscapes hold ancient human tradition and use, the legacy impacts of which may still be seen today.

Wilderness is indeed a myth, a modern Euro-American construct that lacks veracity and validity in the real world. Before we impose more political myth on our landscapes, wouldn’t it be prudent and responsible to see and study them for what they are, ancient homelands and settings of human stewardship, not abandonment?

Selected excerpts:

The forested western Amazon was once thought barren of complex human culture. But researchers are now uncovering enigmatic earthworks left by large, organized societies that once lived and farmed here.

Alceu Ranzi was a geography student in 1977 when he helped discover half a dozen huge, prehistoric rings carved into the landscape in his home state of Acre in western Brazil. At the time, he was helping to conduct the first-ever full archaeological survey of Amazonia, which was being opened up for cattle ranches at a speed that was causing worldwide protests. The earthworks came to light on newly logged land.

The find attracted little attention. The Smithsonian-sponsored National Program of Archaeological Research in the Amazon Basin did not formally announce the rings for 11 years, and even then only in a little-read report. And Ranzi, who went on to become a respected paleontologist, most recently at the Federal University of Acre in Rio Branco, didn’t get back to studying the ditches until more than a decade after that. On a flight to Rio Branco in 1999, he spotted the earthworks again from the air and soon began looking for more. Within a year, he says, “we had found dozens more” of what he calls geoglyphs.

Shaped like circles, diamonds, hexagons, and interlocking rectangles, the geoglyphs are 100 to 350 meters in diameter and outlined by trenches 1 to 7 meters deep. Many are approached by broad earthen avenues, some of them 50 meters wide and up to a kilometer long. The geoglyphs “are as important as the Nazca lines,” Ranzi says, referring to the famed, mysterious figures outlined in stone on the Peruvian coast. …

For most of the last century, researchers believed that the western Amazon’s harsh conditions, poor soils, and relative lack of protein (in the form of land mammals) precluded the development of large, sophisticated societies. According to the conventional view, the small native groups that eked out a living in the region were concentrated around the seasonally flooded river valleys, which had better soil; the few exceptions were short-lived extensions of Andean societies. Meanwhile, the upland and headwaters areas-which include nearly all of western Amazonia-had been almost empty of

humankind and its works.Yet during the past 2 decades, archaeologists, geographers, soil scientists, geneticists, and ecologists have accumulated evidence that, as the geoglyphs team puts it, the western Amazon was inhabited “for hundreds of years” by “sizable, regionally organized populations”-in both the valleys and the uplands. The geoglyphs, the most recent and dramatic discovery, seem to extend across an area of about 1000 kilometers (km) from the Brazilian states of Acre and Rondônia in the north to the Bolivian departments of Pando and the Beni in the south (see map, p.1150). Much of this area is also covered by other, older forms of earthworks that seemingly date as far back as 2500 B.C.E.: raised fields, channel-like canals, tall settlement mounds, fish weirs, circular pools, and long, raised causeways (Science, 4 February 2000, p. 786), suggesting the presence of several cultures over a long period. And on page 1214 of this issue of Science, a U.S.-Brazilian team proposes that indigenous people in the south-central Amazon, 1400 km from Acre, lived in dense settlements in a form of early urbanism and created ditches and earthen walls that some say resemble the geoglyphs (see sidebar).

Cultivated Landscapes Cultural Landscapes The Wilderness Myth

by admin

Comments Off

The Pristine Myth: The Landscape of the Americas in 1492

William Denevan. 1992. The Pristine Myth: The Landscape of the Americas in 1492. Annals of the American Association of Geographers v. 82 n. 3 (Sept. 1992), pp. 369-385.

Full text [here]

Much of the environmental movement is animated, consciously or not, by what geographer William Denevan calls “the pristine myth”—the belief that the Americas in 1491 were an almost untouched, even Edenic land, “untrammeled by man,” in the words of the Wilderness Act of 1964, a U.S. law that is one of the founding documents of the global environmental movement. - Charles C. Mann, 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus.

Selected excerpts:

Abstract. The myth persists that in 1492 the Americas were a sparsely populated wilderness, a world of barely perceptible human disturbance. There is substantial evidence, however, that the Native American landscape of the early sixteenth century was a humanized landscape almost everywhere. Populations were large. Forest composition had been modified, grasslands had been created, wildlife disrupted, and erosion was severe in places. Earthworks, roads, fields, and settlements were ubiquitous. With Indian depopulation in the wake of Old World disease, the environment recovered in many areas. A good argument can be made that the human presence was less visible in 1750 than it was in 1492.

What was the New World like at the time of Columbus? “Geography as it was,” in the words of Carl Sauer (1971). The Admiral himself spoke of a “Terrestrial Paradise,” beautiful and green and fertile, teeming with birds, with naked people living there whom he called “Indians.” But was the landscape encountered in the sixteenth century primarily pristine, virgin, a wilderness, nearly empty of people, or was it a humanized landscape, with the imprint of native Americans being dramatic and persistent? The former still seems to be the more common view, but the latter may be more accurate.

The pristine view is to a large extent an invention of nineteenth-century romanticist and primitivist writers such as W.H. Hudson, Cooper, Thoreau, Longfellow, and Parkman, and painters such as Catlin and Church. The wilderness image has since become part of the American heritage, associated “with a heroic pioneer past in need of preservation” (Pyne 1982, Bowden 1992). The pristine view was restated clearly in 1950 by John Bakeless in his book The Eyes of Discovery:

There were not really very many of these redmen … the land seemed empty to invaders who came from settled Europe . . . that ancient, primeval, undisturbed wilderness . . . the streams simply boiled with fish … so much game . . . that one hunter counted a thousand animals near a single salt lick … the virgin wilderness of Kentucky … the forested glory of primitive America (Bakeless 1950).

But then he mentions that Indian “prairie fires . . . cause the often-mentioned oak openings … Great fields of corn spread in all directions … the Barrens … without forest,” and that “Early Ohio settlers found that they could drive about through the forests with sleds and horses” (Ibid). A contradiction?

In the ensuing forty years, scholarship has shown that Indian populations in the Americas were substantial, that the forests had indeed been altered, that landscape change was commonplace. This message, however, seems not to have reached the public through texts, essays, or talks by both academics and popularizers who have a responsibility to know better. …

Were Native People Keystone Predators? A Continuous-Time Analysis of Wildlife Observations Made by Lewis and Clark in 1804-1806

Kay, Charles E. 2007. Were native people keystone predators? A continuous-time analysis of wildlife observations made by Lewis and Clark in 1804-1806. Canadian Field-Naturalist 121(1): 1–16.

Full text [here]

Note: the The Canadian Field-Naturalist is about a year and a half behind in actual publication, so although the journal issue in which this paper appeared is dated Jan.-March 2007, the publication was available only earlier this week. Full text with cover is [here]. The cover of the issue features the C.M. Russell painting entitled “When Blackfeet and Sioux Meet.”

Selected excerpts:

Abstract: It has long been claimed that native people were conservationists who had little or no impact on wildlife populations. More recently, though, it has been suggested that native people were keystone predators, who lacked any effective conservation strategies and instead routinely overexploited large mammal populations. To test these hypotheses, I performed a continuous time analysis of wildlife observations made by Lewis and Clark because their journals are often cited as an example of how western North America teemed with wildlife before that area was despoiled by advancing European civilization. This included Bison, Elk, Mule Deer, Whitetailed Deer, Blacktailed Deer, Moose, Pronghorn Antelope, Bighorn Sheep, Grizzly Bears, Black Bears, and Grey Wolves. I also recorded all occasions on which Lewis and Clark met native peoples. Those data show a strong inverse relationship between native people and wildlife. The only places Lewis and Clark reported an abundance of game were in aboriginal buffer zones between tribes at war, but even there, wildlife populations were predator, not food-limited. Bison, Grizzly Bears, Bighorn Sheep, Mule Deer, and Grey Wolves were seldom seen except in aboriginal buffer zones. Moose were most susceptible to aboriginal hunting followed by Bison and then Elk, while Whitetailed Deer had a more effective escape strategy. If it had not been for aboriginal buffer zones, Lewis and Clark would have found little wildlife anywhere in the West. Moreover, prior to the 1780 smallpox and other earlier epidemics that decimated native populations in advance of European contact, there were more aboriginal people and even less wildlife. The patterns observed by Lewis and Clark are consistent with optimal foraging theory and other evolutionary ecology predictions.

Introduction

It has long been postulated that native people were conservationists who had little or no impact on wildlife populations (e.g.; Speck 1913, 1939a, 1939b). Studies of modern hunter-gatherers, however, have found little evidence that native people purposefully employ conservation strategies (Alvard 1993, 1994, 1995, 1998a, 1998b; Hill and Hurtado 1996), while archaeological data suggest that prehistoric people routinely overexploited large-mammal populations (Broughton 1994a, 1994b, 1997; Jones and Hilderbrant 1995; Janetski 1997; Butler 2000; Chatters 2004). Elsewhere, I have proposed that native people were keystone predators, who once structured entire ecosystems (Kay 1994, 1995, 1997a, 1997b, 1998, 2002).

To test these competing hypotheses, I performed a continuous-time analysis of wildlife observations made by Lewis and Clark on their expedition across North America in 1804-1806 because their journals are often cited as an example of how the West teemed with wildlife before that area was despoiled by advancing European civilization (Botkin 1995, 2004; Patten 1998: 70; Wilkinson and Rauber 2002; Nie 2003: 1). Lewis and Clark were the first Europeans to traverse what eventually became the western United States, and many of the native peoples they met had never before encountered Europeans. In addition, historians universally agree that Lewis and Clark’s journals are not only among the earliest, but also the most detailed and accurate, especially regarding natural history observations (Burroughs 1961; Ronda 1984; Botkin 1995, 2004). Thus, the descriptions left by Lewis and Clark are thought by many to represent the “pristine” state of western ecosystems (Craighead 1998: 597; Patten 1998: 70; Wilkinson and Rauber 2002; Botkin 2004). Botkin (1995: 1), for instance, described Lewis and Clark’s journey as “the greatest wilderness trip ever recorded.” …

Are Lightning Fires Unnatural? A Comparison of Aboriginal and Lightning Ignition Rates in the United States

Kay, Charles E. Are Lightning Fires Unnatural? A Comparison of Aboriginal and Lightning Ignition Rates in the United States. 2007. in R.E. Masters and K.E.M. Galley (eds.) Proceedings of the 23rd Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference: Fire in Grassland and Shrubland Ecosystems, pp 16-28. Tall Timbers Research Station, Tallahassee, FL.

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

ABSTRACT

It is now widely acknowledged that frequent, low-intensity fires once structured many plant communities. Despite an abundance of ethnographic evidence, however, as well as a growing body of ecological data, many professionals still tend to minimize the importance of aboriginal burning compared to that of lightning-caused fires. Based on fire occurrence data (1970–2002) provided by the National Interagency Fire Center, I calculated the number of lightning fires/million acres (400,000 ha) per year for every national forest in the United States. Those values range from a low of <1 lightning-caused fire/400,000 ha per year for eastern deciduous forests, to a high of 158 lightning-caused fires/400,000 ha per year in western pine forests. Those data can then be compared with potential aboriginal ignition rates based on estimates of native populations and the number of fires set by each individual per year. Using the lowest published estimate of native people in the United States and Canada prior to European influences (2 million) and assuming that each individual started only 1 fire per year—potential aboriginal ignition rates were 2.7–350 times greater than current lightning ignition rates. Using more realistic estimates of native populations, as well as the number of fires each person started per year, potential aboriginal ignition rates were 270–35,000 times greater than known lightning ignition rates. Thus, lightning-caused fires may have been largely irrelevant for at least the last 10,000 years. Instead, the dominant ecological force likely has been aboriginal burning.

keywords: aboriginal burning, Indian burning, lightning-caused fires, lightning-fire ignition rates, potential aboriginal ignition rates.

more »

In Retrospect: Henry T. Lewis

If Omer Stewart was the Father of Anthropogenic Fire Theory, then Henry Trickey Lewis Jr. (1928-2004) was the First-born Son, the standard-bearer, the torch-bearer for 30 years.

Anthropologist Henry T. Lewis was born October 2, 1928 in Riverside, CA. He served in the U.S. military (1947-1954) and as a U.S. National Park ranger. “Hank” as he was fondly referred to, received his BA from Fresno State College (1957) and his PhD from the University of California, Berkeley (1967). Based on his research there, Lewis authored Patterns of Indian Burning in California in 1973. That landmark work expands on Omer Stewart’s general contentions by examining the details of anthropogenic fire in California as practiced by the indigenous residents in pre-contact times.

First hired by San Diego State College (1964-1968) and then by the University of Hawaii (1968-1971), Lewis went on to become Chair of the Department of Anthropology at the University of Alberta in Edmondton (1971-1975 and 1986-1990). There he conducted research in the burning practices of the native peoples of northern Alberta. In addition to written works, Lewis produced a documentary film, The Fires of Spring, in 1978.

Lewis, along with M. Kat Anderson, also compiled, edited, and wrote introductions to Forgotten Fires by Omer Stewart [here]. He was instrumental in getting the work published, fifty years after it had been written by Stewart.

Before The Wilderness: Environmental Management by Native Californians

Blackburn, Thomas C. and Kat Anderson, eds. Before The Wilderness: Environmental Management by Native Californians. 1993. Malki Press - Ballena Press

Selected Excerpts:

CONTENTS

1. INTRODUCTION: MANAGING THE DOMESTICATED ENVIRONMENT

By Thomas Blackburn and Kat Anderson

We did not think of the great open plains, the beautiful rolling hills and the winding streams with tangled growth as ‘wild.’ Only to the white man was nature a`wilderness’ and …the land ‘infested’ with ‘wild’ animals and `savage’ people [Standing Bear, Ogalala Sioux, quoted in Nash 1982].

I have no difficulty in accepting certain spiritual entities in the landscape as domesticated, for the purpose of understanding human action. In the Cape York Peninsula such entities and forces lose their domesticatory qualities when humans are removed from the landscape, and interaction ceases. It is only then that the entire landscape in all its empirical and non-empirical diversity is considered by Aboriginal people to have ‘come wild’ and, thus, to have become potentially dangerous for humans who have lost the practical knowledge for ‘correct’ (i.e., authorized) interaction [Chase 1989:47-8].

During the last two decades, a quiet but nonetheless significant transformation has been occurring in the study of past and present human subsistence systems, and consequently in our understanding of such related (and possibly interrelated) issues as changes in demographic factors, the evolution of complex social and political forms, and the origins and spread of specialized agroecosystems dependent upon domesticated species of plants and animals. A new appreciation for the diversity and potential complexity of nonagricultural economies, in conjunction with a better understanding of the often sophisticated systems of traditional knowledge upon which they are based, has led to a growing recognition that the rigid and rather monolithic conceptual dichotomy traditionally drawn between the seemingly passive `food procurement’ lifestyle of ‘hunter-gatherers’ and the apparently more active `food production’ adaptation of ‘agriculturalists’ is inadequate, overly simplistic, and dangerously misleading. Instead, human adaptive systems increasingly are being seen as occurring along a complex gradient and/or continuum, involving more and more intensive interaction between people and their environment, progressively greater inputs of human energy per area of land, and an expanding capacity to modify or transform natural ecosystems (e.g., Harris 1989)…

Some papers [in this volume] focus rather narrowly on particular techniques of resource utilization or on the micromanagement of individual species, while others discuss the broad management of entire plant communities, resource groups, or populations. Although the evidence that is adduced by the various authors is occasionally fragmentary, and too often more suggestive than decisive, the cumulative effect is compelling, and the final conclusion that emerges seems inescapable and unequivocal: the extremely rich, diverse, and apparently `wild’ landscape that so impressed Europeans at the time of contact-and which traditionally has been viewed as a `natural, untrammeled wilderness’ ever since-was to some extent actually a product of (and more importantly dependent upon) deliberate human intervention. In other words, particular habitats-in a number of important respects-had been domesticated…

Clam Gardens

Williams, Judith. Clam Gardens: Aboriginal Mariculture On Canada’s West Coast. 2006. New Star Books LTD

Pre-Contact West Coast indigenous peoples are commonly categorized in anthropological literature as “hunter gatherers”. However, new evidence suggests they cultivated bivalves in stone-walled foreshore structures called “clam gardens” which were only accessible at the lowest of tides. Judith Williams journeyed by boat around Desolation Sound, Cortes and Quadra Islands and north to the Broughton Archipelago to document the existence of these clam gardens. The result is a fascinating book that bids to change the way we think about West Coast aboriginal culture. — from the back cover

Clam Gardens is a delightful little book, written by an artist and resident of the British Columbian archipelago. A native friend told her about the clam gardens, she investigated them, and “re-discovered” a complex maritime aquaculture of great antiquity. After years of study and pestering of university anthropologists, Judith Williams finally convinced them that the vast network of coastal clam beds from Puget Sound to the Queen Charlotte Islands were largely anthropogenic.

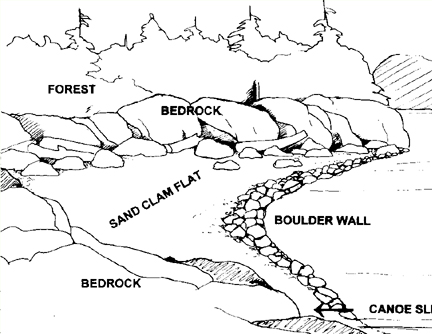

Native people had not only dug natural clam habitat, but, in favourable locations around the Broughton islands, had erected a complex of rock-walled terraces that suggest what we call mariculture.

Bringing these Native mariculture structures to light may be termed, by some, a “discovery,” although the clam gardens, as will be shown, were never lost. Given the evidence of Native knowledge and usage that has also come to light, it’s prudent to sidestep that term. Let’s just say that the story of the re-emergence of these rock structures makes visible to the non-Native world a mindset-altering number of boulder walls, which were erected by Northwest Coast indigenous people at the lowest level of the tide to foster butter clam production. The number of gardens, their long usage, and the labour involved in rock wall construction indicate that individual and clustered clam gardens were one of the foundation blocks of Native economy for specific coastal peoples.

———————————————————————————————-

The Northwest Coast Indians did not need convincing, since they had been building, maintaining, and utilizing the clam gardens for thousands of years. The cultivated landscapes of native North America were not confined to dry land, as Clam Gardens so enjoyably reveals.

The Vegetation of the Willamette Valley

Johannessen, Carl L. , William A. Davenport, Artimus Millet, Steven McWilliams. The Vegetation of the Willamette Valley. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 61 (2), 286–302. 1971.

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

ABSTRACT: The vegetation of the Willamette Valley, Oregon, has been modified by man for centuries. Thc earliest white men described the vegetation as extensive prairies maintained by annual fires set by Indians. The cessation of burning in the 1850s allowed expansion of forest lands on the margins of the former prairies. Today some of these forest lands have completed a cycle of growth, logging, and regrowth. Much of the former prairie is now in large-scale grain and grass seed production and is still burned annually. The pasture lands of the Valley are still maintained as open lands with widely scattered oaks. KEY WORDS: historical vegetation, Indian burning, prairies, vegetation change, Willamette Valley.

The vegetation of the Willamette Valley, Oregon, has changed significantly under human influence. The Indians of this area, at the time of contact with white settlers, set prairie fires annually, which created a prairie/open woodlands complex. The new settlers, who increased rapidly in the mid-nineteenth century, forced the Indians to leave. Their practice of annual burning was temporarily discontinued. White settlers brought modifications of the habitat with their livestock and cropping, and more recently, forestry systems…

The fire-tolerant, widely-spaced oak, fir, or pine seeded the so-called openings to form thickets that have grown to dense woodlands and forest. Firs now dominate these woodlands, because the firs are able to continue vertical growth and reach light more effectively than the broadleaf trees. A complete cycle has occurred in some locations. Mature 70 to 100-year-old fir trees have been harvested from formerly open prairie and parkland, and now new crops of seedlings

have invaded the logged-over areas…

The Long Tom and Chalker Sites

O’Neill, Brian L. , Thomas J. Connolly, and Dorothy E. Freidel, with contributions by Patricia F. McDowell and Guy L. Prouty. A Holocene Geoarchaeological Record for the Upper Willamette Valley, Oregon: The Long Tom and Chalker Sites. University of Oregon Anthropological Papers 61, Published by the Museum of Natural History and the Department of Anthropology, University of Oregon, Eugene. 2004.

Abstract:

Data recovery investigations at two prehistoric sites were prompted by the Oregon Department of Transportation’s realignment of the Noti-Veneta segment of the Florence to Eugene Highway (OR 126) in Lane County, Oregon. The Long Tom (35LA439) and Chalker (35LA420) archaeological sites are located on the floodplain of the Long Tom River in the upper Willamette Valley of western Oregon. Investigations at these sites included an examination of the geomorphic setting of the project to understand the processes that have shaped the landscape and to which its human occupants adapted. The cultural components investigated ranged in age between about 10,000 and 500 years ago.

Geomorphic investigation of this portion of the Long Tom River valley documents a landform history spanning the last 11,000 years. This history is punctuated by periods of erosion and deposition, processes that relate to both the preservation and absence of archaeological evidence from particular periods. The identification of five stratigraphic units, defined from trenching and soil coring in the project area, help correlate the cultural resources found at sites located in the project. Stratigraphic Unit V, found at depths to approximately 250 cm, is a clayey paleosol with cultural radiocarbon ages between 11,000 and 10,500 cal BP. Unit N, with radiocarbon ages between approximately 10,000 and 8500 cal BP, consists of fine-textured sediments laid down during a period of accelerated deposition. An erosional unconformity separates Unit IV from the overlying Unit III. In the archaeological record, this unconformity represents a gap of nearly 3000 years, from 8500 to 5700 cal BP, and corresponds to a period of downcutting in the Willamette system that culminated with a transition from the Winkle to Ingram floodplain surfaces. Unit III sediments are sandy loams within which are found numerous oven features at the Long Tom, Chalker, and other nearby archaeological sites, and date between approximately 5700 to 4100 years ago. A near absence of radiocarbon-dated sediments in the project area between approximately 4100 and 1300 years ago suggests either a lack of use of this area during this period, or an erosional period that was apparently less severe on a regional scale. Units II and I are discontinuous bodies of vertically accreted sediments which represent a period of rapid deposition in the project area during the last 1300 years. It is estimated that Unit I sediments were deposited within the last 500 years.

Investigations at the Long Tom site discovered three cultural components. Components 1 and 3 are ephemeral traces of human presence at the site. The Late Holocene-age Component 1, found within Stratigraphic Units I and II, contains a small assemblage of chipped stone tools and debitage dominated by locally obtainable obsidian. The Early Holocene-age Component 3 contains a single obsidian uniface collected from among a scatter of fire-cracked rock and charcoal found within Stratigraphic Unit IV. Charcoal from this feature returned a radiocarbon age of 9905 cal BP. Contained within Stratigraphic Unit III, Component 2 presents evidence for a concentrated period of site use between approximately 5000 and 4000 cal BP. Geophysical exploration of the deep alluvial sediments with a proton magnetometer located magnetic anomalies, a sample of which was mechanically bisected and hand-excavated for closer analysis. A total of 21 earth ovens and two rock clusters was exposed in sediments associated with radiocarbon ages clustering about 4400 cal BP. Charred fragments of camas bulbs and hazelnut and acorn husks were recovered from the ovens. Few tools were discovered in their vicinity. Larger-scale excavations within the Middle Holocene sediments at the west end of the site discovered what is interpreted as a residential locus.

The Standley Site

Connolly, Thomas J., with contributions by Joanne M. Mack, Richard E. Hughes, Thomas M. Origer, and Guy L. Prouty. The Standley Site (35D0182): Investigations into the Prehistory of Camas Valley, Southwest Oregon. University of Oregon Anthropological Papers No. 43. Published by the Department of Anthropology and Oregon State Museum of Anthropology University of Oregon, Eugene, October 1991.

Abstract:

The Standley site (35D0182) is located at the southern edge of Camas Valley, a small basin on the upper Coquille River of southwestern Oregon. The earliest radiocarbon date from the site is 2350 ± 80 years ago, but obsidian hydration analysis suggests that initial occupation may have begun between 4500 and 5000 years ago. Both obsidian hydration and radiocarbon evidence suggest that occupation was most intense and continuous between 3000 and 300 years ago.

Cultural patterns at the Standley site are unclear at both ends of this occupation span; the remains of the earliest use episodes were disturbed by later prehistoric occupations, and the upper levels of the site were severely disturbed by historic activity. Radiocarbon evidence for the latest occupation period (within the last 500 years) includes dates from the basal portions of posts preserved in the lower levels of the site. The best preserved cultural patterns at the site, presumed to be associated with a set of radiocarbon dates ranging from 1180 to 980 years ago, are within a relatively rock-free area in the north-central portion of the main excavation block. Distinct artifact clusters, and possible structural remains, are present within this area.

The large size of the Standley site, the possible presence of structures, and the variety and density of artifact types present-including an enormous array of chipped stone tools, hammers and anvils, edge-ground cobbles, abrading stones, pestles, stone bowls, clay figurines, painted tablets, and exotic material such as schist, pumice, and steatite-indicate that the site served as a substantial encampment of some duration. There was some evidence for structural remains (posts and bark), but no clear evidence for semisubterranean housepits such as those reported elsewhere in southwest Oregon. The presence of charred hazelnuts and camas bulbs suggest a probable summer-to-fall occupation.

Indians, Fire, and the Land in the Pacific Northwest

Boyd, Robert, editor. Indians, Fire, and the Land in the Pacific Northwest. 1999. Oregon State University Press.

Selected excerpts:

Robert Boyd — Introduction

In May and June of 1792, George Vancouver’s British-sponsored, exploring expedition entered the uncharted waters of Puget Sound.1 Expecting a forested wilderness inhabited by unsophisticated natives, they were surprised at what they found. At Penn Cove, on Whidbey Island:

“The surrounding country, for several miles in most points of view, presented a delightful prospect consisting chiefly of spacious meadows elegantly adorned with clumps of trees; among which the oak bore a very considerable proportion, in size from four to six feet in circumference. In these beautiful pastures … the deer were seen playing about in great numbers. Nature had here provided the wellstocked park, and wanted only the assistance of art to constitute that desirable assemblage of surface, which is so much sought in other countries, and only to be acquired by an immoderate experience in manual labour.”

Among the “pine forests” of Admiralty Inlet, Joseph Whidbey noted “clear spots or lawns … clothed with a rich carpet of verdure.” The “verdure” of these “lawns” included “grass of an excellent quality,” tall ferns “in the sandy soils” and several other plants: “Gooseberrys, Currands, Raspberrys, & Strawberrys were to be found in many places. Onions were to be got almost everywhere.” Whidbey was nostalgic: the lawns had “a beauty of prospect equal to the most admired Parks of England.”

Nearly two centuries later, in 1979, well after the “lawns” observed by Vancouver’s party had been converted to agriculture, the “pine forests” partially cut and managed for timber production, many indigenous species supplanted by Eurasian varieties, and the villages and seasonal camps of the Native Americans replaced by the cities and farms of Euro-American newcomers, anthropologist Jay Miller went into the Methow Valley [north-central Washington] with a van load of [Methow Indian] elders, some of whom had not been there for fifty years. When we had gone through about half the valley, a woman started to cry. I thought it was because she was homesick, but, after a time, she sobbed, ‘When my people lived here, we took good care of all this land. We burned it over every fall to make it like a park. Now it is a jungle. Every Methow I talked to after that confirmed the regular program of burning.

Separated by 187 years of systemic, region-wide ecological change in the Pacific Northwest, these two sets of observations address several themes central to this volume. The Pacific Northwest at first contact with Euro-Americans was not exclusively a forested wilderness. West of the Cascades, as documented in the Vancouver journals, there were large and small prairies scattered throughout a region that was climatically more suited to forest growth. And east of the mountains, as the Methow passage suggests, the forests of the past were quite different, with a minimum of underbrush and clutter. Other differences in local environments were present both east and west.

Vancouver believed that “Nature” alone was responsible for the “luxuriant lawns” and “well-stocked parks”; there is nothing in any of the expedition’s journals suggesting that the Native inhabitants of the “inland sea” had any hand in their existence. Until relatively recently, most anthropologists believed this as well. The traditional stereotype of non-agricultural foraging peoples was that they simply took from the land and did not have the tools or knowledge to modify it to suit their needs. We now know better. Indigenous Northwesterners did indeed have a tool-fire-and they knew how to use it in ways that not only answered immediate purposes but also modified their environment. We now know that the “lawns” that Vancouver observed on Whidbey Island, the prairies that early trappers and explorers described in the Willamette Valley, and the open spaces that led the Hudson’s Bay Company to select the site of Victoria for their headquarters in 1845 had been actively manipulated and managed, if not actually “created,” by their Native inhabitants. Anthropogenic (human-caused) fire was by far the most important tool of environmental manipulation throughout the Native Pacific Northwest.