A Proposal to Eliminate Redundant Terminology for Intra-Species Groups

M. A. Cronin. 2006. A Proposal to Eliminate Redundant Terminology for Intra-Species Groups. Wildlife Society Bulletin 34(1):237–241; 2006

Dr. Matthew Cronin PhD. is Research Associate Professor of Animal Genetics, School of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences, University of Alaska Fairbanks. He is also a member of the Alaska Board of Forestry.

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

Abstract

Many new terms have come into use for intra-species groups of animals defined with genetic criteria including subspecies, evolutionarily significant units, evolutionary units, management units, metapopulations, distinct population segments, populations, and subpopulations. These terms have redundant meanings and can lead to confusion for biologists, managers, and policy makers. I propose that for wildlife management we can simplify intra-species terminology and use only the terms subspecies, populations, and subpopulations. These 3 terms have roots in evolutionary and population biology and can incorporate genetic, demographic, and geographic considerations.

Recently, there has been a proliferation of terms used to describe groups of animals below the species level. For example, Wells and Richmond (1995) identified more than 30 terms used to describe groups generally referring to populations. They also discussed the problems with scientific communication associated with such extensive and redundant terminology.

The importance of intraspecies definitions is exemplified by the United States Endangered Species Act (ESA). The ESA allows listing of species, but it also allows listing of subspecies and distinct population segments (DPS) without clear definition of these terms. The importance of these intra-specific categories is evident in the large number of subspecies and DPS listed under the ESA. For example, more than 70% (57 of 81 listed taxa) of the listed mammals in the United States are identified as subspecies or DPS (http://endangered.fws.gov/wildlife.html). Examples of subspecies listed under the ESA with questionable subspecies status include the California gnatcatcher (Polioptila californica californica, Cronin 1997, Zink et al. 2000) and Preble’s meadow jumping mouse (Zapus hudsonius preblei, Ramey et al. 2005). Other examples of indefinite subspecies designations that affect management and policy are given by Cronin (1993) and Zink (2004).

The importance of clear definition of DPS has been recognized by the agencies administering the ESA (i.e., The United States Fish and Wildlife Service and National Marine Fisheries Service). These agencies noted: “Federal agencies charged with carrying out the provisions of the ESA have struggled for over a decade to develop a consistent approach for interpreting the term ‘distinct population segment’” (Waples 1991:v); and “…it is important that the term ‘distinct population segment’ beinterpreted in a clear and consistent fashion.” (Federal Register 7 Feb. 1996, Vol 61:4722). The National Research Council (NRC 1995:55) recognized the importance of identification of intraspecific units for ESA consideration and stated: “Unless we agree to preserve all endangered or threatened organisms of all taxonomic ranks, we must find ways to identify those groups of organisms we consider to be significant.

The Preble’s meadow jumping mouse: subjective subspecies, advocacy and management

M. A. Cronin. 2007. The Preble’s meadow jumping mouse: subjective subspecies, advocacy and management. Correspondence, Animal Conservation 10 (2007) 159–161

Dr. Matthew Cronin, PhD. is Research Associate Professor of Animal Genetics, School of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences, University of Alaska Fairbanks. He is also a member of the Alaska Board of Forestry.

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

I read with concern the letters to the editor regarding the Preble’s meadow jumping mouse Zapus hudsonius preblei in which Martin (2006) criticized Ramey et al. (2005) for questioning the subspecies designation and the editor for a failed peer review, and Crandall (2006) defended his editorship.

However, the debate over the subspecies status of the Preble’s meadow jumping mouse does not properly acknowledge the subjectivity of the subspecies category. Designation of subspecies status is inherently subjective and this should be openly admitted by both sides of the debate. Accusations of advocacy in this issue are spurious because applied fields such as wildlife conservation or agriculture have inherent advocacy for management objectives. As discussed below, I suggest management units of intraspecific groups should be based on geography, not subjective judgements of subspecies status or genetic differentiation.

The subspecies status of this mouse has been discussed extensively (Ramey et al., 2005, 2006; Crandall, 2006; Martin, 2006; Vignieri et al., 2006) because it has been listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). Briefly, the Preble’s mouse was designated a subspecies with limited descriptive morphological data. There are no diagnostic characters that unequivocally distinguish it from conspecifics. It does not have monophyletic mitochondrial DNA. It may be geographically isolated from, and have different allele frequencies than, con-specific populations. Sample sizes and locations studied are probably small relative to population numbers. The allele frequency differences are for DNA loci that are usually considered selectively neutral. There are no data documenting local adaptation, but it is possible. Given the lack of quantitative criteria for naming subspecies the Preble’s mouse could be considered a legitimate subspecies, or not a legitimate subspecies. My concerns center on the lack of appreciation of the subjectivity of subspecies and on misunderstanding of the nature of advocacy and management in the context of the Preble’s mouse.

It is well established that the subspecies category is subjective (reviewed by Cronin, 1993, 2006; Geist, O’Gara & Hoffmann, 2000; Zink, 2004). This includes other cases involving the ESA (e.g. Cronin, 1997; Zink et al., 2000) and recognition of this could have avoided much of the debate over the Preble’s mouse. …

The subjectivity of subspecies designation is exemplified by the Preble’s mouse. Ramey et al. (2005) used a hypothesis testing approach for genetic, ecological and morphological data and concluded that the subspecies designation was not warranted. Vignieri et al. (2006) presented criteria (no or significantly reduced gene flow), acknowledged subspecies are not well defined, and then concluded the Preble’s mouse is a legitimate subspecies. The ensuing critiques (Crandall, 2006; Martin, 2006; Ramey et al., 2006; Vignieri et al., 2006) demonstrate neither was an absolute result. It is important to recognize that other intra-specific groups that can be listed under the ESA, distinct population segments-DPS and evolutionarily significant units- ESU, are also subjectively defined (Cronin, 2006).

Large predators: them and us!

Dr. Valerius Geist, PhD. 2008. Large predators: them and us! Fair Chase. Vol. 23, No. 3. pp. 14-19

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

We pay close attention to large predators. We do so because we evolved as prey. It was our ancient fate to be killed and eaten, and our primary goal to escape such. Our instincts are still shaped that way.

There is thus a reason why the bloody carnage on our highways is a mere statistic, but the mauling of a person by a grizzly is news. It’s not only that so many fossilized remains of our ancient ancestors are meals consumed by large predators in secluded caves or rock niches, but also that we speciated like large herbivores. That is, our pattern and timing of forming species, of adapting to landscapes, mimics and coincides with that of deer, antelope or cattle, but not that of large carnivores. And that despite our fondness for meat, despite “man the hunter”, and despite the fact that at least one species of humans, Neanderthal man, grew into a super predator.

Large herbivores readily form new species and show a pattern of strong speciation from the equator to the poles, terminating in the cold, glaciated latitudes as “grotesque ice age giants”. Large predators do not. They evolve no grotesque ice age giants comparable to the woolly mammoths among elephants, or the massive-antlered giant deer among deer, the giant sheep, or anything else for that matter as grotesque as ourselves. Is there a more grotesque animal than man? And we did it twice, once as Neanderthal and once as Modern Man. Moreover, herbivores readily form dwarf species under poor ecological conditions such as in rainforests, deserts or predator-free oceanic islands, and they differentiate rapidly into new subspecies as they disperse geographically into new habitats. Predators form no dwarfs, on islands or otherwise. Nor do they segregate sharply into swarms of regional subspecies. Large herbivores do that - and so do humans. Also, our bursts of speciation coincide in time with those of African antelope.

Humans grow small canine teeth, not the large combat-canines typical of apes. Canine reduction is a signature of a common anti-predator adaptation, called the “selfish herd”. In such unrelated individuals cluster together in the open as protection against predation. Herbivores form “selfish herds”, predators do not. Herbivores may “evolve away” huge combat-canines, as shown not only by us, but by deer, horses, rhinos and half a dozen extinct families of large mammalian plant eaters. Carnivores reduce no canines!

Our ancient herbivore root is still reflected in our taste preferences, for when we eat meat we flavor it liberally with plant poisons (pepper, chili, sage, thyme, curry etc). Apparently meat does not really taste “good” till it tastes of “plant”! We also have the herbivore’s craving for salt. So, watch what you reach for next time you get a sizzling steak!

While we may have evolved as hunters, we did not evolve like predators. …

Deer, Elk, Bison Population Dynamics Predators Wildlife Management

by admin

6 comments

Effects of Wolf Predation on North Central Idaho Elk Populations

Idaho Department of Fish and Game, April 4, 2006, Effects of Wolf Predation on North Central Idaho Elk Populations

Full text [here] (2.3 MB)

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Gray wolves (Canis lupus) were reintroduced into Idaho in 1995 and listed as an experimental nonessential population under Section 10(j) of the Endangered Species Act (ESA). Thirty-five wolves were reintroduced and by 2005, an estimated 512 wolves (59 resident packs and 36 breeding pairs) were well distributed from the Panhandle to southeast Idaho. In February 2005, the U.S Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) modified the 10(j) rule which details State options for management of wolves impacting domestic livestock and wild ungulates (Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Regulation for Nonessential Experimental Populations of the Western Distinct Population Segment of the Gray Wolf [50 CFR Part 17]).

The provisions of the 10(j) rule fall short of allowing the states’ preferred management tool of regulated hunting. However, under Section (v): “If gray wolf predation is having an unacceptable impact on wild ungulate populations (deer, elk, moose, bighorn sheep, mountain goats, antelope, or bison) as determined by the respective State and Tribe (on reservations), the State or Tribe may lethally remove wolves in question. In order for the provision to apply, the States or Tribes must prepare a science-based document that: 1) describes what data indicate that ungulate herd is below management objectives, what data indicate there are impacts by wolf predation on the ungulate population, why wolf removal is a warranted solution to help restore the ungulate herd to State or Tribal management objectives, the level and duration of wolf removal being proposed, and how ungulate population response to wolf removal will be measured; 2) identifies possible remedies or conservation measures in addition to wolf removal; and 3) provides an opportunity for peer review and public comment on their proposal prior to submitting it to the Service for written concurrence.”

This document supports the State’s determination that gray wolf predation is having an unacceptable impact on a wild ungulate population. Specifically, this document reviews the Idaho Department of Fish and Game (IDFG) evaluation of the effect of wolf predation on an elk population below state management objectives. The document includes a review of elk population data, the cause-specific mortality research being conducted on elk, the wolf population data, and the modeling conducted to simulate impacts of wolf predation on elk using known population parameters. Additionally, this report identifies remedies and conservation measures that have already been attempted to reduce impacts of the multiple factors influencing the current elk population status, and identifies management actions and objectives to improve and monitor elk populations in the Lolo Zone.

This evaluation addresses the criteria outlined under 10J SEC. (v) and provides detailed information on the following topics:

1. What is the elk management objective?

Management objectives for elk in the Lolo Zone (Game Management Units [GMU] 10 and 12) is to maintain an elk population consisting of 6,100 – 9,100 cows and 1,300 – 1,900 bulls. Individual GMU objectives for the Lolo Zone are: 4,200 – 6,200 cows and 900 – 1,300 bulls in GMU 10; and 1,900 – 2,900 cows and 400 – 600 bulls in GMU 12. Population objectives for GMU 17 are 2,400 – 3,600 cows and 650 – 975 bulls. Objectives are based on the Department’s best estimate of elk habitat carrying capacity and acknowledge a reduction in habitat potential from the conditions observed in the 1980s. In 1989, the Department estimated 16,500 elk in the Lolo Zone. Current cow and bull objectives (7,400) are 60% of the 1989 estimate of 12,378 cow and bull elk. In 2006, the Department estimated 4,233 cow and bull elk in the Lolo Zone.

2. Data used to evaluate populations in relation to management objective.

IDFG biologists use aerial surveys to monitor elk populations throughout the state, including GMUs 10, 12, and 17. Surveys are designed to provide a statistically and biologically sound sampling framework. Biologists generate estimates (and confidence intervals) of population size, age ratios (e.g., calves:100 cows) and sex ratios (e.g., bulls:100 cows) from the survey data. Current status of elk populations are: 2,276 cows and 504 bulls in GMU 10; 978 cows and 475 bulls in GMU 12; and 2,076 cows and 486 bulls in GMU 17.

3. Data that demonstrate the impact of wolf predation.

Elk survival rates were estimated using radio-collared animals. A total of 64 adult cow elk were captured, radio-collared, and monitored in GMUs 10 and 12 in 2002-2004 (90 elk-years). Combining samples across areas and years produced point estimates of annual elk survival (includes all mortality sources) ranging from 75% to 89%, with a 3-year weighted average of 83%. More recently, survival from March 2005 through February 2006 was 77%.

Nine of 25 (36%) mortalities among adult cow elk from January 2002 through March 2006 were attributed to wolves. Wolf-caused mortality was not detected during 2002 or 2003; whereas 1 death was attributed to wolf predation in 2004 and 8 through 1 March 2006. Three additional losses resulted from predation, but species of predator could not be determined; 4 were attributed to mountain lions; and 9 were attributed to factors other than predation (e.g., hit by a vehicle, harvested, disease) or cause of death could not be determined.

Similar survival and cause-specific mortality data for elk in GMU 17 does not exist because of logistical difficulties with capture and monitoring of elk in designated Wilderness.

IDFG used the available data and assumptions based on peer-reviewed literature to simulate the impacts of wolf predation on elk populations in north-central Idaho. All simulations revealed a lack of cow elk population growth in the presence of wolf predation. Most simulations suggest moderate to steep declines in abundance caused by wolf predation. Regardless of the approach we used to model elk populations, all simulations used suggest wolves are limiting population growth.

4. Why wolf removal is warranted.

Several factors may have contributed to the elk population decline in the Lolo Zone, including harvest management, habitat issues, and predation. The Department and collaborators have aggressively addressed each of these factors for a number of years. Nevertheless, the Lolo Zone does not meet state management objectives. Without an increase in cow elk survival, the Lolo Zone elk population is unlikely to achieve management objectives.

The available data indicate that wolf predation is, at a minimum, partly additive and likely contributes to low adult female elk survival. Based on our evaluation and analysis, the State has determined that wolf predation is having an unacceptable impact on elk populations in the Lolo Zone. This evaluation demonstrates that wolves play an important role in limiting recovery of this elk population and that wolf removal is warranted as allowed under the 10(j) rule.

Management of most big game populations is accomplished through regulated harvest by hunters. A reduction in wolf numbers in the Lolo Zone would ideally be accomplished through regulated take by sportsmen rather than by state or federal agencies, and all alternatives for removal would be explored.

5. Level and duration of wolf removal.

During year one, we propose to reduce the wolf population in the Lolo Zone by no more than 43 of the estimated 58 wolves (75% reduction) that currently occupy the zone. The first year reduction represents about 8% of the estimated 512 wolves present in Idaho in 2005. The wolf population will be maintained at 25-40% of the pre-removal wolf abundance for 5 years. Concurrently, we will monitor elk and wolf populations. After 5 years, results will be analyzed and a peer-reviewed manuscript will be prepared that evaluates the effect of fewer wolves on elk population dynamics.

6. How will ungulate response be measured?

We will monitor the performance of elk populations in GMUs 10 and 12 with ongoing statewide research efforts on elk and mule deer and within the context of Clearwater Region wildlife management activities. The information will include fecundity, age/sex-specific survival rates, and cause-specific mortality rates. We will use aerial surveys to monitor elk populations in GMUs 10, 12, and 17. In GMUs 10 and 12, complete surveys will be scheduled for 2006, 2008, and 2010. In GMU 17, complete surveys will be scheduled for 2007 and 2010. Composition surveys will be flown in intervening years. In GMUs 10 and 12, we will document elk survival rates and cause-specific mortality factors from samples of radio-marked adult cow and calf elk.

Deer, Elk, Bison Population Dynamics Predators Wildlife Management Wildlife Policy

by admin

Comments Off

The Truth about Our Wildlife Managers’ Plan to Restore “Native” Ecosystems

George Dovel. 2008. The Truth about Our Wildlife Managers’ Plan to Restore “Native” Ecosystems. The Outdoorsman, Number 30, Aug-Sept 2008.

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

In 1935 when Cambridge University botanist Arthur Tansley invented the term “ecosystem” in a paper he authored, he was attempting to define the system that is formed from the relationship between each unique environment and all the living organisms it contains.

Ecologists concluded that these individual systems evolved naturally to produce an optimum balance of plants, herbivores that ate the plants, and carnivores that ate the herbivores. Many accepted this “food chain” theory as a permanent state of natural regulation and a theory was advanced that certain “key” species of plants and animals were largely responsible for maintaining these “healthy” ecosystems.

But subsequent archeological excavations or core samples of the buried layers of periods in time revealed that these “perfected” ecosystems were actually in a continuing state of change which could be caused by changes in weather, climate or various organisms. They concluded that parasites or other organisms that were not included in their food chain charts often caused radical population changes in one or more of the keystone species.

The “Balance-of-Nature” Myth Keeps Surfacing

In 1930 noted Wild Animal Ecologist Charles Elton wrote, “The ‘balance of nature’ does not exist and perhaps never has existed. The numbers of wild animals are constantly varying to a greater or less extent, and the variations are usually irregular in period and always irregular in amplitude (being ample).” Yet 33 years later, in a highly publicized Feb. 1963 National Geographic article, titled, “Wolves vs. Moose on Isle Royale,” fledgling Wolf Biologist David Mech and his mentor, Durward Allen, claimed just the opposite. …

Debunking the “Balance-of-Nature” Myth

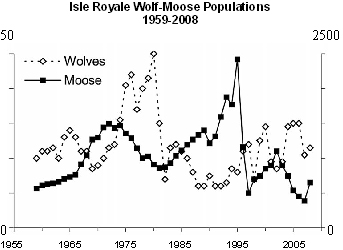

The extreme “spikes” (highs and lows) in numbers of keystone species resulting from reliance on the theory that “natural regulation” will produce a “balance” are evidence that the so-called “Balance of Nature” is a pipe dream. One fairly long-term example of this is seen in the following graph recording 50 years of wolf and moose populations on Isle Royale National Park in Michigan.

Population Dynamics Wildlife Habitat Wildlife Management Wildlife Policy

by admin

Comments Off

Yellowstone’s Destabilized Effects, Science, and Policy Conflict

Frederick H. Wagner. 2006. Yellowstone’s Destabilized Effects, Science, and Policy Conflict. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

Review by Cliff White, Parks Canada, Banff, Alberta, Ca. [first published in Mountain Research and Development Vol 28 No 2 May 2008]

In an influential book of the 1960s, Fire and Water: Scientific Heresy in the Forest Service, Ashley Schiff (1962) documented how, for over 3 decades, the United States Forest Service subverted ecological science to justify an agency policy of total fire suppression. This policy was especially flawed in southeastern pine forests that evolved under a regime of periodic burning. Schiff’s exposé showed how, in a technologically-based society, science could be systematically manipulated to become clever advocacy for a political end. The book became a must read for a generation of ecological researchers and natural resource policy specialists.

Fred Wagner, formerly associate dean of the Natural Resources department at Utah State University, continues this tradition of exceptional scholarship to describe policy-driven research in Yellowstone, the United States’ flagship national park. Ironically, the general political and ecological scenario is in many respects similar to the southeastern pine forest debacle—management actions driven by a strong political constituency were imposed on an ecosystem ill-adapted to them, and scientists were unwilling or unable to evaluate and document obviously negative outcomes. In Schiff’s example, the fire suppression program was rooted in a strong American land management and resource husbandry movement of the early 1900s. In Wagner’s work, Yellowstone’s management and scientific research is motivated by equally powerful, but opposite societal forces supporting wilderness or “natural regulation.”

For those unfamiliar with the Yellowstone situation, removal of native peoples from the park in the 1800s and reduction in large carnivores in the early 1900s provided favorable conditions for the population of elk (Cervus elaphus), a generalist herbivore, to increase dramatically. After government biologists observed the effects of high densities of elk on soil and vegetation in the 1920s, park rangers routinely culled the herd for over 4 decades. In the 1960s, recreational game hunters lobbied to take over the cull. Given the potential political incompatibility of sport hunting with conservation in one of the world’s premier national parks, the federal government made the decision to cease elk culling. Park managers and senior scientists then carefully selected a generation of researchers to evaluate the revised policy. The result was a new paradigm of “natural regulation” that was underlain by 4 key hypotheses:

1) long-term human hunting, gathering and burning had not substantially influenced the ecosystems of North America’s Rocky Mountains;

2) ungulate populations in Yellowstone were, over the long term, generally high;

3) carnivore predation was a “non-essential adjunct” having minimal influence on elk numbers; and

4) high elk numbers would not cause major changes in plant communities, ungulate guilds, and other long-term ecosystem states and processes.

Although the natural regulation paradigm seems rather farfetched today, remember that it was born in the 1960s, a time of antiestablishment flower children, when wilderness was untrammeled by Native Americans, when biologist and author Farley Mowat’s wolves subsisted on mice (Mowat 1963), and the only “good fires” were caused by lightning. Moreover, an excellent argument can be made that ecological science needs large “control ecosystems” with minimal

human influences.

In the 40 or so years since the implementation of the national regulation policy, both the National Park Service and outside institutions conducted many ecological studies. These culminated in 1997 with a congressionally mandated review by the National Research Council. It is this wealth of research and documentation that Fred Wagner uses to evaluate changes over time in the Yellowstone ecosystem. He provides meticulous summaries of research in chapters on each of several different vegetation communities, the ungulate guild, riparian systems, soil erosion dynamics, bioenergetics, biogeochemistry and syntheses for the “weight of evidence” on the primary drivers of ecological change. This background allows readers to develop their own understanding on the results of this textbook case of applied ecological science.

Wagner clearly shows that most studies did not support the hypotheses of natural regulation. In cases where studies did seem to support a hypothesis, methods and results were suspect. The elk population clearly grew beyond predictions, some plants and animals began to disappear, and the importance of Yellowstone’s lost predators and Native Americans should have become undeniable. However, faced with these incongruities, park managers still supported the natural regulation policy. Some researchers closely affiliated with management then began to invoke climate change as a potential factor for observed ecosystem degradation, but the evidence for this was similarly tenuous. On the basis of the almost overwhelming evidence, Wagner concludes that much of the park-sponsored science on the natural regulation paradigm “missed the mark” and that “Yellowstone has been badly served by science.”

For scientists or managers working in similar arenas of high ecosystem values and intense politics, the book’s concluding chapters will be of most interest. Here, Wagner explores the interface between science and policy. As an alternate model to Yellowstone’s research and management system, he promotes an adaptive management process (Walters 1986) where an open political environment exists between scientists, stakeholders, and managers. Here, a controversial management option such as natural regulation could have been evaluated, as Wagner advises, “in the bright light of objective scientific understanding.” Stakeholders and managers could then use this knowledge as a basis to adjust policies quickly before grave ecological consequences occur.

However, the limited and, in terms of literature review, dated discussion of the public policy process is a weakness of the book. A more complete discussion of ecosystem management in a highly polarized political environment could have described a range of current approaches for collaborative problem solving. In fact, another recent review of wildlife management in Yellowstone concluded that the major problem facing the park was not the quantity or quality of the science, but the lack of mechanism to resolve conflicts between and within groups of scientists, stakeholders and agency managers. Gates et al (2005) remark that “collaboration is necessary to define what is acceptable; science is necessary to define what is possible; organizing people to use knowledge to design and implement management in the face of uncertainty is fundamental.” Applied ecological researchers, progressive managers, and stakeholders with a strong civic responsibility should strive for this ideal. Our parks, and indeed most places on our planet, need high-profile models such as Yellowstone, where science should help people to understand, value, and maintain the biodiversity of ecosystems.

REFERENCES

Gates CC, Stelfox B, Muhley T, Chowns T, Hudson RJ. 2005. The Ecology of Bison Movements and Distribution in and beyond Yellowstone National Park. Calgary, Canada: Faculty of Environmental Design, University of Calgary.

Mowat F. 1963. Never Cry Wolf. Toronto, Canada: McClelland and Stewart.

Schiff AL. 1962. Fire and Water: Scientific Heresy in the Forest Service. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Walters C. 1986. Adaptive Management of Renewable Resources. New York: Macmillan.

Idaho Wildlife Services Wolf Activity Report

USDA-APHIS Idaho Wildlife Services Wolf Activity Report Fiscal Year 2007

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

Introduction

This report summarizes Idaho Wildlife Services’ (WS) responses to reported gray wolf depredations and other wolf-related activities conducted during Fiscal Year (FY) 2007 pursuant to Permit No. TE-081376-12, issued by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) June 16, 2006. This permit allows WS to implement control actions for wolves suspected to be involved in livestock depredations and to capture non-depredating wolves for collaring and re-collaring with radio transmitters as part of ongoing wolf monitoring and management efforts.

Investigations Summary

WS conducted 133 depredation investigations related to wolf complaints in FY 2007 (as compared to 104 in 2006, an increase of almost 27%). Of those 133 investigations, 88 (~66%) involved confirmed depredations, 19 (~14%) involved probable depredations, 20 (~15%) were possible/unknown wolf depredations and 6 (~5%) of the complaints were due to causes other than wolves.

more »

What They Didn’t Tell You About Wolf Recovery

Dovel, George. 2008. What They Didn’t Tell You About Wolf Recovery. The Outdoorsman, Bull. No. 26, Jan-Mar 2008.

Full text [here]

Also includes:

Geist, Val. 2008. Two Letters from Dr. Valerius Geist. The Outdoorsman, Bull. No. 26, Jan-Mar 2008.

Dovel, George. 2008. Attempt to End Airborne Predator Control-How Alaska’s Governor Responded. The Outdoorsman, Bull. No. 26, Jan-Mar 2008.

Collinge, Mark. 2008. Relative risks of predation on livestock posed by individual wolves, black bears, mountain lions and coyotes in Idaho. The Outdoorsman, Bull. No. 26, Jan-Mar 2008.

Dovel, George . 2008. Outdoorsmen Document Surplus Wolf Kills Hunters Comment on Declining Elk Harvests. The Outdoorsman, Bull. No. 26, Jan-Mar 2008.

The Outdoorsman is edited and published by George Dovel. For subscription info please contact:

The Outdoorsman

P.O. Box 155

Horseshoe Bend, ID 83629

Selected excerpts:

By 2006 many people in the West were aware that minimum estimated fall wolf numbers in Idaho, Montana and Wyoming already exceeded the criteria for delisting wolves by several hundred percent. But few seem aware that the FWS agenda to allow this to happen was exposed by wildlife ecologist Dr. Charles Kay way back in 1993 – before any Canadian wolves were transplanted into the three Northern Rocky Mountain states.

In an article entitled, “Wolves in the West – What the government does not want you to know about wolf recovery” in the August 1993 issue of Petersen’s Hunting, Dr. Kay asked the question, “If wolves are brought back how many are enough?” He pointed out that the federal government’s recovery plan announced that when 10 breeding pairs (approximately 100 wolves) existed in each of the three recovery areas for three consecutive years, wolves would be declared recovered and removed from the Endangered Species list.

Then Dr. Kay also pointed out that to prevent harmful inbreeding and protect against random environmental changes, most scientists believed that a minimum population of 1,500 wolves must be achieved. When he attempted to find out why such a low number was being sought for recovery FWS could not produce evidence of any scientific research to justify such a low recovery number. …

Six years after the 10 breeding pairs per area was established as the criterion for delisting, Wolf Project Leader Ed Bangs included Appendix 9 in the draft EIS stating that a questionnaire had been mailed to 43 wolf biologists in Nov.-Dec. 1992 asking whether they agreed with the minimum criteria of 10 pairs established in 1987. The names of the 25 biologists who reportedly responded and the specific answers they provided were not included.

Meanwhile Bangs initiated a letter-writing campaign to discredit Dr. Kay among his peers and elsewhere. Instead Kay’s scientific associates defended him and rebuked Bangs for his attempt to destroy Dr. Kay’s scientific reputation while also attempting to suppress legitimate scientific opinion. …

more »

Polar Bear Population Forecasts: A Public-Policy Forecasting Audit Working Paper

Armstrong, J. Scott, Kesten C. Green, Willie Soon. 2008. Polar Bear Population Forecasts: A Public-Policy Forecasting Audit Working Paper Version 68: March 28, 2008

Full text [here]

Abstract: Calls to list polar bears as a threatened species under the U.S. Endangered Species Act are based on forecasts of substantial long-term declines in their population. Nine government reports were prepared to support the listing decision. We assessed these reports in light of evidence-based (scientific) forecasting principles. None referred to works on scientific forecasting methodology. Of the nine, Amstrup, Marcot and Douglas (2007) and Hunter et al. (2007) were the most relevant to the listing decision. Their forecasts were products of complex sets of assumptions. The first in both cases was the erroneous assumption that General Circulation Models provide valid forecasts of summer sea ice in the regions inhabited by polar bears. We nevertheless audited their conditional forecasts of what would happen to the polar bear population assuming, as the authors did, that the extent of summer sea ice would decrease substantially over the coming decades. We found that Amstrup et al. properly applied only 15% of relevant forecasting principles and Hunter et al. only 10%. We believe that their forecasts are unscientific and should therefore be of no consequence to decision makers. We recommend that all relevant principles be properly applied when important public policy decisions depend on accurate forecasts.

Key words: adaptation, bias, climate change, decision making, endangered species, expert opinion, extinction, evaluation, evidence-based principles, expert judgment, extinction, forecasting methods, global warming, habitat loss, mathematical models, scientific method, sea ice.

Dr. J. Scott Armstrong is professor of Marketing at The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania. Professor Armstrong is internationally known for his pioneering work on forecasting methods. He is author of Long-Range Forecasting, the most frequently cited book on forecasting methods, and Principles of Forecasting, voted the “Favorite Book – First 25 Years” by researchers and practitioners associated with the International Institute of Forecasters. He is a co-founder of the Journal of Forecasting, the International Journal of Forecasting, the International Symposium on Forecasting, and forecastingprinciples.com [here]. He is a co-developer of new methods including rule-based forecasting, causal forces for extrapolation, simulated interaction, and structured analogies.

In 1989, a University of Maryland study ranked Professor Armstrong among the top 15 marketing professors in the U.S. In 1996, he was selected as one of the first six Honorary Fellows by the International Institute of Forecasters. He serves or has served on Editorial positions for the Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, the Journal of Business Research, Interfaces and the International Journal of Forecasting , and other journals. He was awarded the Society for Marketing Advances Distinguished Scholar Award for 2000. One of the most frequently cited marketing professors worldwide, his “first-author” citation rate currently averages over 200 per year.

Dr. Kesten C. Green is Senior Research Fellow, Business and Economic Forecasting Unit, Monash University, Australia. He is Co-director of the Forecasting Principles site, forecastingprinciples.com [here], and a member of the Editorial Board, Foresight: The International Journal of Applied Forecasting and the Editorial Board, Forecasting Letters. He is also Founder and former Director of Infometrics Limited, a leading New Zealand economic forecasting and consulting house. He is also Founder and former Director of Bettor Informed, a computerised horse-racing information magazine based on assessment of probabilities under different conditions.

Dr. Willie Soon is a physicist at the Solar, Stellar, and Planetary Sciences Division of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and an astronomer at the Mount Wilson Observatory. Among his many published research studies is Reconstructing Climatic and Environmental Changes Of The Past 1000 Years: A Reappraisal with Sallie Baliunas, Craig Idso, Sherwood Idso, and David R. Legates. Energy & Environment, Vol. 14, Nos. 2 & 3, 2003.

Cattle and Wildlife on the Arizona Strip

Gardner, Cliff, Edwin R. Riggs, and Newell Bundy. Cattle and Wildlife on the Arizona Strip. 1993. Gardner File Nos. 3-a. and 8-b.

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

TED RIGGS is one of the best known Mule Deer hunters in the West. During a lifetime spent in the Country known as the Arizona Strip, Ted has killed 40 bucks with antler spreads exceeding 30 inches, ten of which measured over 36 inches, and fifteen in the 34 to 36 inch range. His widest buck had a spread of 43 1/2 inches, and scored 249 6/8 Boone and Crockett points.

Ted is best known for the many Mule Deer he has taken, but to those that know him best, his real prowess is as a trapper and tracker.

“I’ve been trapping for 65 years now. When I was 8, I can remember my father would set the traps for me and I would go bury them. By trapping, I was able to put myself through High School during the Great Depression.”

Ted was born in 1916 in Kanab, Utah. After being discharged from duty with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in 1945 he went to work for U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

“At that time Ranchers were losing 4500, of their calves and lambs to predators. We shot coyotes, used coyotes getters, poison (strychnine and arsenic and later 1080). Four years after we began the ranchers’ calf crop jumped to 90%. ‘1080’ was the most effective, we would inject it into the meat of mustangs or burros and scatter it across the desert once a year.”

Ted spent 28 years as a guide, mostly hunting Mule Deer. …

The Destruction of the Sheldon

Gardner, Cliff. The Destruction of the Sheldon. 1995. Gardner File No. 22-a.

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

IN THE SPRING of 1989 Bertha and I were invited by Harry and Joy Wilson to visit the Sheldon National Wildlife Refuge, which is located North of Winnemucca in Northwestern Nevada right up against the Oregon line. Created for the purpose of protecting pronghorn antelope, the Refuge comprises a huge area, somewhere around 460,000 acres. The thing Harry wanted us to see was the destruction that was occurring on the Refuge because of mismanagement by federal agents.

At that time the agency in charge, the US Fish and Wildlife Service, was nearing the end of their long effort to rid the Refuge of livestock permittees of which Harry and Joy were among the last. So it had been a frustrating thing for them, as it had been for all the other permittees as they were being forced off - not only from the standpoint of all they were losing as livestock operators, but also from the standpoint of having to watch the area they loved go down hill.

Harry had spent his entire life there in the Virgin Valley, his father having lived there even before the Refuge had been created, so he remembered what it was like before the government created the Refuge. Harry related how abundant the antelope had been in the 1930’s and 40’s. He said that during his youth it had been a family tradition to count the antelope each Fall as they left the high country and headed for the Black Rock Desert for the Winter. He said at times antelope would come through the valley strung out in bunches of a thousand or more. He estimated that at that time there were at least ten thousand antelope summering on the Big Spring Table each year. (Big Spring Table being a high mesa that lay just North of where they lived). But now, after years of government management, there were few antelope left.

I related to what Harry was saying, for in Ruby Valley our family had similar experiences, only with us it was with deer. Back in the 1940’s and even up until the late 1960’s, we would watch the foothills above the ranch as the deer migrate South in the Fall and North in the Spring. And they too would migrate through in bunches of a thousand head or more if the weather caught them right. And like Harry, we too had seen the great herds diminish because of stupid government management.

How Many Wildebeest Do You Need?

Norton-Griffiths, Mike. How Many Wildebeest Do You Need? World Economics.Vol. 8, No. 2, April–June 2007.

Mike Norton-Griffiths, D.Phil. is a long-time resident of Kenya, where he researches into issues of land use economics and the economic foundations of conservation and land use policy.

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

So, how many wildebeest do you need? How many elephants is enough? And what do you need them for? These are not trivial questions, for they focus attention on the need for some hard decisions. A conservation biologist will maintain that while the actual number of wildebeest at any particular time is irrelevant, what is important is to ensure adequate space and habitat so the population can vary as it must in response to environmental vicissitudes. In contrast, a free market environmentalist would approach this problem secure in the knowledge that there is indeed a market for wildebeest which will deliver a socially and economically efficient number of animals. Naturally, neither of these views is wrong-which is not the same as saying that either is right.

Consider as an example the Serengeti migratory wildebeest population which, despite 40 years of scientific monitoring and research, has effortlessly grown from around 250,000 individuals in the 1950s to some 1.5 million today, going up a bit in good (rainy) years and down a bit in drier years (Figure 1). That this extraordinary phenomenon still exists is due to the vast 30,000 km2 area over which they are able to migrate, from the Serengeti National Park in Tanzania during the wet season up to the Maasai Mara Game Reserve in Kenya during the dry season…

Here now is a problem to exercise both the conservation biologist and the free market environmentalist, for what is the optimal number of wildebeest given that tourists probably only need to see some 300,000 to experience the raw majesty of the migration? Kenya will balance the benefits to be gained from developing agriculture on what was previously pastoral land against any possible tourism losses, while Tanzania may still wish to have as many wildebeest as possible to enhance the international reputation of the Serengeti National Park. Difficult choices indeed…

The Need for the Management of Wolves

Bergerud, Arthur T. The Need for the Management of Wolves-An Open Letter. 2007. Rangifer, Special Issue No. 17, 2007: The Eleventh North American Caribou Workshop, Jasper, Alberta, Canada, 24-27 April, 2006.

Note: A.T. Bergerud is former chief biologist of Newfoundland. He has been a population ecologist involved in research on caribou populations in North America since 1955. Along with Stuart N. Luttich and Lodewijk Camps, Bergerud authored the just released The Return of Caribou to Ungava [here].

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

Abstract: The Southern Mountain and Boreal Woodland Caribou are facing extinction from increased predation, predominantly wolves (Canis lupus) and coyotes (Canis latrans). These predators are increasing as moose (Alces alces) and deer (Odocoileus spp.) expand their range north with climate change. Mitigation endeavors will not be sufficient; there are too many predators. The critical habitat for caribou is the low predation risk habitat they select at calving: it is not old growth forests and climax lichens. The southern boundary of caribou in North America is not based on the presence of lichens but on reduced mammalian diversity. Caribou are just as adaptable as other cervids in their use of broadleaf seed plant as forage. Without predator management these woodland caribou will go extinct in our life time.

Introduction

A major ecological question that has been debated for 50 years is: are ecosystems structured from top-down (predator driven) or bottom-up (food limited) processes (Hairston et al., 1960; Hunter & Price, 1992)? Top-down systems can vary widely from sea mammals such as sea otters (Enhydra lutris) to ground nesting birds. The sea otter causes an elegantly documented trophic cascade through sea urchins (Strongylocentrotus spp.) down to kelp beds (Estes & Duggins, 1995). Ground nesting waterfowl and gallinaceous birds are not limited by food resources but are regulated by top-down nest predation caused by a suite of predators, mainly skunks (Mephitis mephitis), red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) and crows (Corvus brachyrhynchos) (Bergerud, 1988; 1990; Sargeant et al., 1993). Management decisions depend on understanding which structure is operational.

Discussions on top-down or bottom-up have been recently been rekindled with the introduction of wolves (Canis lupus) to Yellowstone National Park and Idaho in 1995 (Estes, 1995; Kay, 1995; 1998). The elk/wapiti (Cervus elaphus) population in Yellowstone prior to introduction were basically limited by a density-dependent shortage of food (Singer et al., 1997) but now is declining from wolf predation (Crête, 1999; White & Garrott, 2005). All three states, Wyoming, Idaho, and Montana, are litigating the federal government to get the wolf delisted so they can start wolf management to maintain their stocks of big-game.

We conducted a 30 year study (1974 to 2004) of two caribou (Rangifer tarandus) populations, one in Pukaskwa National Park (PNP) and the other on the Slate Islands in Ontario, relative to these two paradigms of top-down or bottom-up. (Bergerud et al., this conference). In Pukaskwa National Park, there was an intact predator-prey system including caribou, moose (Alces alces), wolves, bears (Ursus americanus), and lynx (Lynx canadensis). On the Slate Islands, our experimental area, there were no major predators of caribou. The PNP populated was regulated top-down by predation and existed at an extremely low density of 0.06 caribou per km2, whereas the population on the Slate Islands averaged 7-8 animals/km2 over the 30 years (100X greater than in PNP). In the absence of predators, these island caribou were regulated from the bottom-up by a shortage of summer foods and the flora was impacted, resulting in some floral extinctions. The extremely low density of only 0.06 caribou per km2 in PNP is normal for caribou populations coexisting with wolves (Bergerud, 1992a: Fig. 1, p. 1011). The top-down predator driven ecosystem of caribou in PNP also applies in Canada to moose, elk, and black-tailed deer (Odocoileus hemionus) that are in ecosystems with normal complements of wolves and bears (Bergerud, 1974; Bergerud et al., 1983; Bergerud et al., 1984; Messier & Crete, 1985; Farnell & McDonald, 1986; Seip, 1992; Messier 1994; Hatter & Janz 1994; Bergerud & Elliott, 1998; Hayes et al., 2003).

Of all the predator driven ecosystems of cervids, the threat of extinction is most eminent for the southern mountain and boreal woodland caribou ecotypes, both classified as threatened (COSEWIC 2002, Table 11). These herds are declining primarily from predation by wolves plus some mortality from bears. From west to east the equations for continued persistence are not encouraging — in British Columbia the total of the southern mountain ecotype is down from 2145 (1992-97) to 1540 caribou (2002-04) and four herds number only 3, 4, 6, and 14 individuals (Wittmer et al., 2005). In Alberta, the range has become fragmented and average recruitment recently was 17 calves/100 females, despite high pregnancy rates (McLoughlin et al., 2003). That low calf survival is less than the needed to maintain numbers - 12-15% calves or 22-25 calves per 100 females at 10-12 moths-of-age to replace the natural mortality of females (Bergerud, 1992a; Bergerud & Elliott 1998). In Saskatchewan, populations are going down, ?=0.95 (Rettie et al., 1998). The range is retreating in Ontario (Schaefer, 2003) as southern groups disappear; in Labrador the Red Wine herd is now less than 100 animals (Schmelzer et al., 2004); in southern Quebec, there may be only 3000 caribou left (Courtois et al., 2003), and in Newfoundland, herds are in rapid decline from coyotes (Canis latrans) and bear predation (G. Mercer and R. Otto, pers. comm.). In Gaspé, the problem for the endangered relic herd is also coyotes and bear predation (Crête & Desrosiers, 1995). In Gaspé, these predators have been reduced and there is a plan in place to continue adaptive management (Crête et al., 1994). Do we have to wait until the herds are listed as endangered to manage predators?

Wilderness and Political Ecology: Aboriginal Influences and the Original State of Nature

Kay, Charles E., and Randy T. Simmons, eds. Wilderness and Political Ecology: Aboriginal Influences and the Original State of Nature. 2002. University of Utah Press

Selected Excepts:

Preface — CHARLES E. KAY AND RANDY T. SIMMONS

Most environmental laws and regulations, such as the Wilderness Act, the Park Service Organic Act, and the Endangered Species Act, assume a certain fundamental state of nature, as does all environmental philosophy, at least in the United States (Keller and Turek 1998, Krech 1999; Spence 1999; Burnham zooo). Included in these core beliefs is the view that the Americas were a wilderness untouched by the hand of man until discovered by Columbus and that this wilderness teemed with untold numbers of bison (Bison bison), passenger pigeons (Ectopistes migratorius), and other wildlife, until despoiled by Europeans. In this caricature of the pristine state of the Americas, native people are seldom mentioned (Sluyter 2001), or if they are, it is usually assumed that they were either poor, primitive, starving savages, who were too few in number to have had any significant impact on the natural state of American ecosystems (Forman 2001), or that they were “ecologically noble savages” and original conservationists, who were too wise to defile their idyllic “Garden of Eden” (Krech 1999). As Park Service biologist Thomas Birkedal (1993:228) noted, “The role of prehistoric humans in the history of park ecosystems is rarely factored into … the equation. If acknowledged at all, [the] former inhabitants are … relegated to what one cultural anthropologist … calls the ‘Native Americans as squirrels’ niche: they are perhaps curious critters, but of little consequence in the serious scheme of nature.”

This view of native people, and the “natural” state of pre-European America, though, is not scientifically correct. Moreover, we suggest that it is also racist (Sluyter 2001). In fact, as Bowden (1992), Pratt (1992), and others have documented, the original concept of America as wilderness was invented, in part, by our forefathers to justify the theft of aboriginal lands and the genocide that befell America’s original owners. Even those who view native people as conservationists are guilty of what historian Richard White (1995:175) describes as “an act of immense condensation. For in a modern world defined by change, whites are portrayed as the only beings who make a difference. [Environmentalists may be] … pious toward Indian peoples, but [they] don’t take them seriously [for they] don’t credit [native people] with the capacity to make changes.”

Contrary to this prevailing paradigm, the following chapters demonstrate that native people were originally more numerous than once thought, that native people were generally not conservationists-as conservation is not an evolutionary stable strategy unless the resource is economical to defend, and that native people in no way, shape, or form were preservationists, as that term applies today (Berkes 1999:91; Smith and Wishnie 2000; Sluyter 2001). Instead, native people took an active part in managing their environment. Moreover, changes wrought by native people were so pervasive that their anthropogenic, managed environment was thought to be the “natural” state of the American ecosystem (Buckner 2000). In short, the Americas, as first seen by Europeans, had not been created by God, but instead those landscapes had largely been crafted by native peoples (Hallam 1975) …

Wolves in Russia

Graves, Will N. Wolves in Russia: Anxiety Through the Ages. 2007. Detselig Enterprises LTD.

Selected excerpts and ordering info [here]

Review by Bear Bait

I finished it. Dryer than a popcorn fart. A sort of disjointed set of citations. Somehow the organization could have been better. Or so I think.

Wolves in Russia was PhD edited for facts and translations, but perhaps not for literary style. I have no doubt as to the veracity of the material, just some discomfort in how it was presented. I have neither the experience or talent to detail how it should have been done, however. My cop-out.

Wolves In Russia can be used as a reference, but you had better be an expert reader of Russian like the author. The book is edited by Dr. Valerius Geist, PhD, P.Biol., Prof. Emeritus U of Calgary, Alberta, Canada. Wolves in Russia has excellent scientific trappings, if not the order and style that would make it more digestible for me.

But after reading Will Graves’ gleanings from the historical record of the last 150 years, it becomes clear that Russians, and that means all those people under the rule of Mother Russia in the last 150 years, have every right to fear wolves.

There is an old Russian saying, “I kill the wolf not because he is grey. I kill the wolf because he kills my sheep.” Russians don’t hate wolves for being wolves. They hate them for what they do to their lives.

If you were rural and subsistence living in Russia during the last 150 years, you would have known political upheaval, government intervention and non-intervention, money for government services, and times without money for government services. You would have experienced long periods of gun control and being defenseless against violent people and predators. Hundreds of millions of Russians died in that 150 year period, and probably the majority at the hands of their own government by acts of omission as well as commission.

The apparent difference between the pioneer experience in the U.S. as opposed to Europe is the amount of liberty in the U.S. The freedom to own and bear arms was essential to a pioneering people who were able to succeed without undue influence of wolves in their lives. In the U.S. wolves were shot, on sight, by European immigrants because their life and cultural experiences were that wild predators consumed the means of human survival. “I shoot the wolf because he eats my sheep.” It is likely that pre-European North American residents felt the same way.