The Tumblebug Fire

On September 12, 2010, two lightning-ignited fires were reported to be burning in Tumblebug Creek, a tributary of the Middle Fork of the Willamette River. Three weeks later 14,570 acres had burned, including ~5,000 acres of old-growth spotted owl forests, and $100 million in timber had been destroyed. The real tragedy, however, is that the Tumblebug Fire is a harbinger of larger, more severe, and more damaging fires to come.

How this fire happened, and why it is a prelude to even greater disaster, is the subject of this essay.

The 1.7 million acre Willamette National Forest [here] extends from the Calapooia Divide in Douglas County, Oregon, to the Santiam Divide in Marion County. It encompasses the headwaters of following major watersheds: the Middle and North Forks of the Willamette River, the McKenzie River, and the North and South Forks of the Santiam River. East to west the Willamette NF begins at the crest of the Oregon Cascades and slopes westward to the foothills of the Willamette Valley.

Situated as it is on the west side of the Cascades, the Willamette NF is one of the most productive forests in the world. Temperate climate, abundant rainfall, and rich volcanic soils engender forests that are capable of growing nearly a billion (with a “b”) board feet per year.

In 2009 28 million board feet (MMBF) were harvested, less than 3% of the annual growth. In prior years the harvest was:

2008 _ 30.6 MMBF

2007 _ 29.6

2006 _ 49.8

2005 _ 71.1

2004 _ 59.9

2003 _ 20.5

2002 _ 20.2

2001 _ 18.8

Source: Region 6 Cut and Sold Reports and Volume Under Contract [here]

In no year in the past decade has more than 7.1% of annual growth been harvested. Yet the forests have continued to grow, not only the trees but also the brush, and the biomass has built up.

Biomass is fuel — the accumulated growth is accumulated fuel that will burn. The more fuel, the hotter and more intense the fires.

The Willamette NF is primed to burn in a forest fire larger and more intense than any in state history.

The Wilderness Society in a recent analysis named the Willamette NF as the top U.S. forest in terms of “carbon density” — that is, accumulated fuel per acre.

Pacific Northwest Forests Top at Storing Carbon

TWS Press Release, March 4, 2010 [here]

SEATTLE — The top ten carbon storing national forests in the U.S. are all found in the moist westside forests in Washington, Oregon and southeast Alaska, according to a new Wilderness Society analysis. The analysis, based on United States Forest Service data, ranks the forests among the Earth’s greatest “carbon banks.” …

The ten national forests in the U.S. with the highest carbon density — Willamette (OR), Olympic (WA), Umpqua (OR), Gifford Pinchot (WA), Siuslaw (OR), Mt. Hood (OR), Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie (WA), Siskiyou (OR), Tongass (AK), and Rogue River (OR) — do something that humans can’t see with their own eyes: they breathe in air filled with carbon, such as carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas that contributes to global warming, and store it within the trees cells, roots and even soil. …

What TWS failed to note is that carbon is fuel, fuel burns, and dense fuels burn intensely.

The Tumblebug Fire spread quickly through the built up fuels. Kim Titus, Branch Director in Planning, Science and Resource Information for the Bureau of Land Management’s Oregon State Office in Portland, was acting Forest Supervisor. After the fire was mostly contained, she wrote in an OpEd column published in the Eugene Register Guard [here]:

In the last two months, most of my time has been in support of fire suppression efforts on both the Canal Creek and Tumblebug fires.

The latter will be the third-largest fire ever fought on the forest, and it grew exponentially in just a few days. It required 1,200 firefighters and associated support services and burned almost 15,000 acres. As I write, the Tumblebug complex is still not contained, but the rains have stopped the progression of the fire.

When a fire starts on federal land, our first priority is always firefighter and public safety, and secondly to protect important structures and natural resources.

But this time we didn’t try to put the entire fire out. We strategically put our resources into the north and portions of the east and west sides of the fire, to protect the Middle Fork of the Willamette River and private land, and to provide a buffer from the east winds that were driving the fire. The other side of the fire was simply monitored. …

In other words, the formal fire suppression policy stated in the Willamette NF Fire Plan is no longer fully in force. The WNF Fire Plan says:

[S]carcity of old growth habitat and the importance of it to the recovery of the northern spotted owl and other late-successional species impose constraints on the use of prescribed natural fire. …

The relative scarcity of old growth habitat imposes constraints on Wildland Fire Use (WFU). …

Wildland Fire Use is currently allowed in the Mount Jefferson, Mount Washington and the Three Sisters Wildernesses. … Following current Federal fire policy, fire starts in all other areas of the forest will receive an appropriate management response but the fire will not be managed for resource benefits. …

All wildfires will receive an Appropriate Management Response. The selected strategies and tactics will be those that provide first for public and firefighter safety and second will be the most cost-effective commensurate with the objectives for the Management Area (MA) and/or Land Allocation within which the fire occurs. …

Fire should be suppressed at the lowest acreage possible.

Instead of suppressing at the lowest possible acreage and protecting old-growth habitat, the Tumblebug Fire was only partially suppressed. Granted, this fire was severe and fast-moving as it crowned through stands of all sizes and age classes, and there was little the firefighters could do on all fronts to contain it. But the mission creep away from aggressive suppression portends larger fires in the future.

The WNF Fire Plan also notes:

Fire records from 1980-2003 show a total 2,903 starts for 65,592 acres. The annual average fire occurrence for the Forest is 121 fires per year burning 2733 acres.

Fires in 1997, 2004, and 2007 burned 15,000, 25,000, and 6,000 acres respectively.

The Tumblebug Fire, at 14,760 acres the third largest fire in forest history, was the second record fire this Century. The B&B Fire (2003) burned a little over 20,000 acres on the Willamette NF, mostly in the Mt. Jefferson Wilderness (total acreage was 90,769 acres, the majority of that on the Deschutes NF).

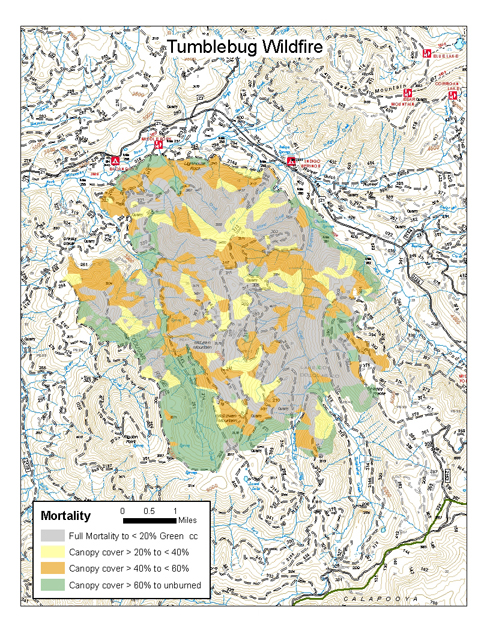

Preliminary assessment of the Tumblebug Fire damage [here] indicated that about 6,400 acres or 43% of the burn area experienced total tree mortality. Another 1,900 acres experienced near total mortality (a more accurate assessment will be made this summer).

Tumblebug Fire mortality map, courtesy USFS. Click for larger image.

About 5,000 acres (or more) of northern spotted owl habitat was lost. Large diameter trees that had withstood frequent fires in the past were killed by this fire. Riparian zones burned, and endangered salmon and bull trout streams were subjected to increased sediment this winter. About 4,200 acres (30% of the fire area) consisted of plantations resulting from past even-aged harvest ranging in age from 10 to 45 years.

Commenter Timbo writes [here]:

A small portion of the Tumblebug Burn (the very lowest elevations) used to have a frequent, low-intensity [anthropogenic] fire regime, but that ended over 100 years ago. Those open, grassy stands where the pines were have grown over with a closed canopy — letting a wildfire burn in those fuel conditions has no ecological benefits without prior restoration efforts.

The bulk of the Burn (which includes 4,000 or 5,000 acres of [former] plantations [formerly] ranging in age from 10 to 45 years), contains several large ridges with elevations up to 6,100 feet that did not have a frequent fire regime. While those places in the watershed have always burned severely and infrequently, resetting that clock can hardly be called an ecological benefit.

An as-yet-unreleased USFS study determined that about 6,800 acres of the two highest mortality classes occurred in mature stands (as opposed to the many 10- to 40-year old plantations within the fire, about 30% of the acreage). Using a conservative estimate of 35 MBF/acre for the mature forest, about 240 MMBF of merchantable timber volume was killed by the fire on those acres alone.

The total timber volume killed in this one fire is roughly equivalent to the total harvest from the Willamette NF over the last 10 years — but it is still only a third of the annual growth across the entire forest.

Forest fire is the rapid combustion of hydrocarbons. The products of combustion include carbon-dioxide. But not all the carbon is volatilized. The post-fire dead, dry biomass loadings may exceed those from before the fire, when much of that biomass was green.

The quantity of dead dry fuel per acre has likely increased on many acres, especially in formerly mature forest stands. Hence the fire hazard has not been abated. The brush will sprout, and in a few years the fine fuels will have built up again, The likelihood of a severe return fire in 10 to 15 years is high.

The policy transition away from timber harvest has resulted in enormous fuel build-ups on the Willamette NF. In the absence of biomass removal (or safe disposal) through restoration forestry practices or industrial timber harvest, that fuel will continue to accumulate until it explodes in another catastrophic fire. And another, and another.

With each passing year the threat of severe fire increases. The threat of extreme resource degradation from catastrophic fire also increases. The biomass has accumulated and will continue to accumulate until disaster strikes.

The Tumblebug Fire is thus a precursor of far larger and more damaging fires to come. Unless some serious effort is made to save the Willamette NF from impending disaster, the now green habitat will explode into a fire of unimaginable proportions. The same is true of other National Forests in Oregon, including the Umpqua NF and the Rogue River-Siskiyou NF. Both are on TWS’s list of the top ten most fuel-dense forests

Disaster looms. It is predictable and preventable disaster. To ignore that certain tragic outcome, to do nothing in face of a known, well-understood, treatable risk, is the height of social, environmental, and economic irresponsibility. There will be no way to “bail out” the landscape or the communities, as the investment banks have been bailed out after their crash and burn in 2008.

We must act now, or we will suffer dire consequences to our forests, landscapes, watersheds, and communities that will last lifetimes.

by YPmule

by stump

The Forest Service has no plans for any timber harvest in the burn area this year and minimal roadside harvest next year.

This land is within the matrix, and timber harvest is supposed to be part of the land use plan.

by Foo Furb

What the USFS isn’t doing on the Tumblebug borders on criminal.

It definitely displays incompetence. Incompetence and disregard.

If the USFS is incapable of managing wildfires or forestlands, they should give them back to the Counties, to the Tribes, or sell them to private interests.

This is ridiculous.

Excellent! Posted to the YPTimes.