The Fictional Ecosystem and the Pseudo-science of Ecosystem Management

Travis Cork III. 2010. The Fictional Ecosystem and the Pseudo-science of Ecosystem Management. W.I.S.E. White Paper No. 2010-3, Western Institute for Study of the Environment.

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

LAND USE CONTROL has long been the goal of the statist element in our society. Zoning was the first major attempt at land use control. Wetland regulation and the Endangered Species Act have extended some control, but nothing has yet brought about a general policy of land use control. Ecosystem management is an attempt to achieve that end.

The fictional ecosystem

In The Use and Abuse of Vegetational Concepts and Terms, A. G. Tansley coined the term “ecosystem.” Tansley rejected the “conception of the biotic community” and application of the “terms ‘organism’ or ‘complex organism’” to vegetation. “Though the organism may claim our primary interest, when we are trying to think fundamentally we cannot separate them from their special environment, with which they form one physical system. It is the systems so formed which, from the point of view of the ecologist, are the basic units of nature on the face of the earth. … These ecosystems, as we may call them, are of the most various kinds and sizes… which range from the universe as a whole down to the atom” 1/

Tansley further writes “[e]cosystems are extremely vulnerable, both on account of their own unstable components and because they are very liable to invasion by the components of other systems. … This relative instability of the ecosystem, due to the imperfections of its equilibrium, is of all degrees of magnitude. … Many systems (represented by vegetative climaxes) which appear to be stable during the period for which they have been under accurate observation may in reality have been slowly changing all the time, because the changes effected have been too slight to be noticed by observers.” 2/

Lackey confirms writing “[t]here is no ‘natural’ state in nature; it is a relative concept. The only thing natural is change, some-times somewhat predictable, oftentimes random, or at least unpredictable. It would be nice if it were otherwise, but it is not.” 3/

The ecosystem may be the basic unit of nature to the ecologist, that is—man, but it is not the basic unit to nature. Its proponents confirm that it is a man-made construct.

We are told in Creating a Forestry for the 21st Century: The Science of Ecosystem Management that “ecosystems, in contrast to forest stands, typically have been more conceptual than real physical entities.” 4/

The Report of the Ecological Society of America Committee on the Scientific Basis for Ecosystem Management tells us “[n]ature has not provided us with a natural system of ecosystem classification or rigid guidelines for boundary demarcation. Ecological systems vary continuously along complex gradients in space and are constantly changing through time.” 5/

“People designate ecosystem boundaries to address specific problems, and therefore an ecosystem can be as small as the surface of a leaf or as large as the entire planet and beyond.” 6/

“Defining ecosystem boundaries in a dynamic world is at best an inexact art,” says the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) in its 1995 publication, Integrating Social Science and Ecosystem Management: A National Challenge.

“Among ecologists willing to draw any lines between ecosystems, no two are likely to draw the same ones. Even if two agree, they would recognize the artificiality of their effort…” 7/ …

Defining, Identifying, and Protecting Old-Growth Trees

Mike Dubrasich. 2010. Defining, Identifying, and Protecting Old-Growth Trees. W.I.S.E. White Paper 2010-1. Western Institute for Study of the Environment.

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts [here]

IN ORDER TO SOLVE our current forest crisis and protect our old-growth, it is useful to understand what old-growth trees are and how to identify them in the field.

At first blush this may seem to be a simple problem, but it is not, and much confusion and debate abounds over the issue. Old-growth trees are “old,” but how old does a tree have to be to qualify as “old-growth”? And what is the difference between an individual old-growth tree and an old-growth stand of trees? Why does it matter?

Some rather sophisticated understanding of forest development is required to get at the root of these questions. …

Silvicultural research and the evolution of forest practices in the Douglas-fir region

Curtis, Robert O.; DeBell, Dean S.; Miller, Richard E.; Newton, Michael; St. Clair, J. Bradley; Stein, William I. 2007. Silvicultural research and the evolution of forest practices in the Douglas-fir region. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-696. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 172 p.

Full text may be downloaded [here]

Selected excerpts:

Abstract

Silvicultural practices in the Douglas-fir region evolved through a combination of formal research, observation, and practical experience of forest managers and silviculturists, and changing economic and social factors. This process began more than a century ago and still continues. It has had a great influence on the economic well-being of the region and on the present characteristics of the region’s forests. This long history is unknown to most of the public, and much of it is unfamiliar to many natural resource specialists outside (and even within) the field of silviculture. We trace the history of how we got where we are today and the contribution of silvicultural research to the evolution of forest practices. We give special attention to the large body of information developed in the first half of the past century that is becoming increasingly unfamiliar to both operational foresters and — perhaps more importantly — to those engaged in forestry research. We also discuss some current trends in silviculture and silviculture-related research.

Introduction

Forestry is the science, art, and practice of creating, managing, using, and conserving forests and associated resources for human benefit to meet desired goals, needs, and values (Helms 1998). Silviculture is that portion of the field of forestry that deals with the knowledge and techniques used to establish and manipulate vegetation and to direct stand and tree development to create or maintain desired conditions. It is the application of knowledge of forest biology and ecology to practical forestry problems.

Modern forestry evolved over more than a century in the United States and over several centuries in Europe and elsewhere in the world. This long history is not well known to many people interested in forestry, and many natural resource professionals — including a good many foresters — know little of the scientific and social background that influenced the historical development of forestry and forest science. Yet, many modern questions and controversies are merely variations on those of the past. Any balanced consideration of current problems and possible solutions requires an understanding of how we got where we are today. …

A complete and detailed history of North American forestry and forestry research would be an enormous undertaking, far beyond our capabilities. We here confine ourselves to the much more limited subject of the development of silvicultural research and practice in the Douglas-fir region of the Pacific Northwest. In doing so, we take a broad view of silviculture, including silvics, nursery practice, seeding and planting, forest genetics, and those aspects of forest mensuration related to stand development. Our discussion will deal primarily with Douglas-fir as it occurs in western Washington and Oregon, but will also touch on important associated species. We concentrate on events and research in Washington and Oregon, only briefly touching on more or less parallel developments in adjacent Canada and California. We delve very lightly into the enormously important topic of fire and its effects. Likewise, we touch only briefly on the important role of silviculture in forest health issues such as prevention and control of root diseases, insect attacks, animal damage, and similar matters. We consciously bypass much of the large body of related work in physiology and ecology. Our main focus will be on the silvicultural research bearing on stand regeneration and stand management.

We give special attention to the period before World War II (WWII) and treat subsequent years in less detail, in part because the pre-WWII period is least familiar to the current generation of foresters. Most research in this early period was carried out by the U.S. Forest Service, the number of people involved was small, and they often worked on a variety of topics. The early researchers included some truly remarkable people who made enormous contributions. The memory of these people and their contributions should not be lost. …

Reduced Fire Frequency Changes Species Composition of a Ponderosa Pine Stand

Alan Dickman. 1978. Reduced Fire Frequency Changes Species Composition of a Ponderosa Pine Stand. Journal of Forestry, January 1978.

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

Abstract

In the Umpqua National Forest, Oregon, a 35-acre ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa Laws.) stand situated in the midst of a Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii [Mirb.]Franco) forests is being invaded by Douglas-fir seedlings as a result of reduced fire frequency within the last 50 years. In earlier times frequent ground fires kept Douglas-fir at a minimum.

Pine Bench, an area on the Umpqua National Forest, Oregon, is undergoing a drastic change in species composition. The understory, which according to an early settler, Jessie Wright (personal communication, 1975), was open and grassy until a half-century ago, now contains thickets of Douglas-fir that are shading out seedlings of the overstory ponderosa pines. A study was made to determine the cause and extent of this shift. …

Results

The size-class distribution (fig .1) shows that among the large trees there are far more ponderosa pines than Douglas-firs, while among the small trees there are far more Douglas-firs than ponderosa pines. The age class distribution (fig. 2) shows that the change occurred rather suddenly. …

The linear regressions show that Douglas-fir grows faster than ponderosa pine on Pine Bench; Douglas-fir appearing in the same size-class is actually younger. Therefore, the difference in the large number of old ponderosa pine and the small number of old Douglas-fir is actually even greater than the size-class distribution indicates.

The shift in, species composition began, then, when the middle-aged trees were seedlings. The number of Douglas-fir germinating and surviving was relatively small and stable until 1925, but thereafter increased steadily up to the present.

Discussion

The change seems too quick and drastic to be a result of natural succession. Grazing does not seem responsible, either. According to Jessie Wright (personal communication) cattle were driven through Pine Bench from 1917 to 1952 on their way between summer and winter grazing areas. The cattle were never on the bench long, however, and their impact was slight. Furthermore, Mrs. Wright told me that they grazed fir in preference to pine.

Reduced fire frequency seems the most likely cause of the invasion. …

Two factors may have combined to reduce the frequency of fires on Pine Bench in this century. First is the absence of Indian or settler-caused fires, although as early as 1840 the number of Indians in the North Umpqua Valley was very small (Bakken 1970). An equally likely cause is the suppression of fires by the U.S. Forest Service.

By 1920, a Forest Service fire lookout was established on Illahee Rock, only four miles from Pine Bench, although it was not until the introduction of aerial fire-fighting techniques that control became highly effective. Douglas-firs living through the 1920s and 1930s would have almost been assured of survival once the more effective fire suppression of later decades began.

Prescribed burning has been proven valuable and workable in maintaining ponderosa pine stands (Weaver 1964, 1965) and should be considered for Pine Bench.

Mistreatment of the economic impacts of extreme events in the Stern Review Report on the Economics of Climate Change

Roger Pielke Jr. 2007. Mistreatment of the economic impacts of extreme events in the Stern Review Report on the Economics of Climate Change. Global Environmental Change 17 (2007) 302–310.

Roger Pielke Jr. is a Fellow of the Center for Science and Technology Policy Research, University of Colorado.

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

Abstract

The Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change has focused debate on the costs and benefits of alternative courses of action on climate change. This refocusing has helped to move debate away from science of the climate system and on to issues of policy. However, a careful examination of the Stern Review’s treatment of the economics of extreme events in developed countries, such as floods and tropical cyclones, shows that the report is selective in its presentation of relevant impact studies and repeats a common error in impacts studies by confusing sensitivity analyses with projections of future impacts. The Stern Review’s treatment of extreme events is misleading because it overestimates the future costs of extreme weather events in developed countries by an order of magnitude. Because the Stern Report extends these findings globally, the overestimate propagates through the report’s estimate of future global losses. When extreme events are viewed more comprehensively the resulting perspective can be used to expand the scope of choice available to decision makers seeking to grapple with future disasters in the context of climate change. In particular, a more comprehensive analysis underscores the importance of adaptation in any comprehensive portfolio of responses to climate change.

Introduction: exploiting an excess of objectivity

In a provocative article titled “How Science Makes Environmental Controversies Worse” Daniel Sarewitz explains that scientific research results in an “excess of objectivity” in political debates (Sarewitz, 2004). What he means with this phrase is that in most (if not all) cases of political conflict involving science, available research is sufficiently diverse so as to provide a robust resource for political advocates to start with a conclusion and then selectively pick and choose among existing scientific studies to buttress their case. Simply put, to cherry pick, to take the best leave the rest. …

Using a spatially explicit ecological model to test scenarios of fire use by Native Americans: An example from the Harlem Plains, New York, NY

William T. Bean and Eric W. Sanderson. 2007. Using a spatially explicit ecological model to test scenarios of fire use by Native Americans: An example from the Harlem Plains, New York, NY. Ecological Modelling 211 (2008) pp. 301–308.

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

Abstract

It is unclear to what extent Native Americans in the pre-European forests of northeast North America used fire to manipulate their landscape. Conflicting historical and archaeological evidence has led authors to differing conclusions regarding the importance of fire. Ecological models provide a way to test different scenarios of historical landscape change.We applied FARSITE, a spatially explicit fire model, and linked tree mortality and successional models, to predict the landscape structure of the Harlem Plains in pre-European times under different scenarios of Native American fire use. We found that annual burning sufficed to convert the landscape to a fire-maintained grassland ecosystem, burning less often would have produced a mosaic of forest and grasslands, and even less frequent burning (on the order of once every 20 years) would not have had significant landscape level effects. These results suggest that if the Harlem Plains had been grasslands in the 16th century, they must have been intentionally created through Native American use of fire.

Introduction

The use of fire by Native Americans in northeast North America has been the subject of much debate shared among a broad group of ecologists, archaeologists and environmental historians. Some like Day (1953), Cronon (1983) and Krech (1999) believe that Native Americans used fire often to manipulate their landscape, and that these manipulations may have taken place over broad extents in the pre-European forests.

Skeptics admit that the rate of forest fires around a village might have been elevated over a background rate because Northeast Indians were using fire for cooking and pottery. However, they find little evidence that fires were widespread or intentionally set (Russell, 1983). Early settlers rarely offer first-hand accounts of fires and fewer still tell of intentional burning. These, Russell says, might be attributed to escaped fires.

Intentional burning has many potential benefits for hunting and gathering peoples: frequent fires can clear tangled vegetation, making it easier to travel through and to clear for horticulture (Lewis, 1993); fire can create vegetation mosaics that are attractive to deer and other game species, and make hunting easier (Williams, 1997); sometimes people set fires just for fun (Putz, 2003).

Of course different fire regimes have different effects on the ecology of Northeast forests. A frequent fire regime would favor a grassland with lingering oaks, a fire-tolerant genus (Swan, 1970; Abrams, 1992, 2000). Less frequent fire would lead to regenerating forests (Abrams, 1992). Understanding Native American use of fire is important for understanding the structure and function of pre-European forests.

Spark and Sprawl: A World Tour

Stephen J. Pyne. 2008. Spark and Sprawl: A World Tour. Forest History Today, Fall 2008.

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

Wildland-urban interface” is a dumb term for a dumb problem, and both have dominated the American fire scene for nearly twenty years. It’s a dumb term because “interface” is a pretty klutzy metaphor and because the phenomenon of competing borders it describes is more complex than that geeky term suggests. At issue is a scrambling of landscape genres beyond the traditional variants of the American pastoral. It is a mingling of the quasi-urban and the quasi-wild into something that, depending on your taste, resembles either an ecological omelet or a coniferous strip mall. That means it also stirs together urban fire services with wildland fire agencies, two cultures with no more in common than an opera house and a grove of old-growth ponderosa pine. It is an unstable alloy, a volatile compound of matter and antimatter, and it should surprise no one that it explodes with increasing regularity.

It’s a dumb problem because technical solutions exist. We know how to keep houses from burning on the scale witnessed over the past two decades. We know convincingly that combustible roofing is lethal; we have known this for maybe ten thousand years. The wildland-urban interface (WUI) fire problem (a.k.a., the interface or I-zone) thus differs from fire management in wilderness, for example, where fire practices must be grounded, if paradoxically, in cultural definitions and social choices; there is no code to ensure that the right fire happens in the right way.

That the intermix problem persists testifies to its relatively trivial standing in the larger political universe, even as construction pushes ever outward into the environmental equivalent of subprime landscapes, which from time to time then crash catastrophically. In that regard it remains on the fringe. …

The relationship of respiratory and cardiovascular hospital admissions to the southern California wildfires of 2003

R. J. Delfino, S. Brummel, J. Wu, H. Stern, B. Ostro, M. Lipsett, A. Winer, D. H. Street, L. Zhang, T. Tjoa and D. L. Gillen. 2008. The relationship of respiratory and cardiovascular hospital admissions to the southern California wildfires of 2003. Occup. Environ. Med. 2009;66;189-197.

Note: lead author is Dr. Ralph J. Delfino, Epidemiology Department, School of Medicine, University of California, Irvine, CA

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

ABSTRACT

Objective: There is limited information on the public health impact of wildfires. The relationship of cardiorespiratory hospital admissions (n=40 856) to wildfirerelated particulate matter (PM2.5) during catastrophic wildfires in southern California in October 2003 was evaluated.

Methods: Zip code level PM2.5 concentrations were estimated using spatial interpolations from measured PM2.5, light extinction, meteorological conditions, and smoke information from MODIS satellite images at 250 m resolution. Generalised estimating equations for Poisson data were used to assess the relationship between daily admissions and PM2.5, adjusted for weather, fungal spores (associated with asthma), weekend, zip code-level population and sociodemographics.

Results: Associations of 2-day average PM2.5 with respiratory admissions were stronger during than before or after the fires. Average increases of 70 mg/m3 PM2.5 during heavy smoke conditions compared with PM2.5 in the pre-wildfire period were associated with 34% increases in asthma admissions. The strongest wildfire-related PM2.5 associations were for people ages 65–99 years (10.1% increase per 10 mg/m3 PM2.5, 95% CI 3.0% to 17.8%) and ages 0–4 years (8.3%, 95% CI 2.2% to 14.9%) followed by ages 20–64 years (4.1%, 95% CI 20.5% to 9.0%). There were no PM2.5–asthma associations in children ages 5–18 years, although their admission rates significantly increased after the fires. Per 10 mg/m3 wildfire-related PM2.5, acute bronchitis admissions across all ages increased by 9.6% (95% CI 1.8% to 17.9%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease admissions for ages 20–64 years by 6.9% (95% CI 0.9% to 13.1%), and pneumonia admissions for ages 5–18 years by 6.4% (95% CI 21.0% to 14.2%). Acute bronchitis and pneumonia admissions also increased after the fires. There was limited evidence of a small impact of wildfire-related PM2.5 on cardiovascular admissions.

Conclusions: Wildfire-related PM2.5 led to increased respiratory hospital admissions, especially asthma, suggesting that better preventive measures are required to reduce morbidity among vulnerable populations.

We present here the largest study to date evaluating the relationships of hospital admissions for cardiorespiratory outcomes to wildfire-associated PM2.5 using data from the catastrophic wildfires that struck southern California in the autumn of 2003. We linked PM2.5 concentrations estimated at the zip code level to a population-based dataset of hospital admissions using spatial time series analyses of data before, during and after the fires. Strong, dry winds from inland deserts fanned flames from nine distinct fires, which burned nearly three quarters of a million acres and destroyed approximately 5000 residences and outbuildings. The wildfires generated large amounts of dense smoke that covered much of urban southern California (2003 population of 20.5 million). PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations far exceeded US federal regulatory standards. The goal of the present study is to assess the impact of this large wildfire event on serious morbidity.

Rhymes With Chiricahua.

Stephen J. Pyne. 2009. Rhymes With Chiricahua. Copyright 2009 Stephen J. Pyne

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

While the Chiricahua Mountains are famous for many reasons to many groups, they are rarely known for their fires. They should be. Some start from lightning, some from ranchers. Some are set by rangers, or are allowed some room to roam by them. Some are left by transients in the person of hunters, campers, and hikers. In recent years more are associated with traffic across the border with Mexico. The Chiricahuas have, at the moment, less of this than other border-hugging districts within the Coronado National Forest, but fires to distract, fires to hide, and fires abandoned by illegal border-crossers are becoming more prominent. All in all, it’s an interesting medley.

Mark Twain once observed that history doesn’t repeat itself but it sometimes rhymes. These days it seems there is a lot of rhyming in the Chiricahuas as fires echo a fabled but assumed vanished past. This revival moves the Chiricahuas, among the most isolated of mountain ranges, a borderland setting for fire as for other matters, close to the core of contemporary thinking about managing fire in public wildlands.

The Chiricahuas –- actually a giant, deeply eroded and flank-gouged massif –- are among the southernmost of America’s Sky Islands, compact mountain ranges that both cluster and stand apart from one another, like an archipelago of volcanic isles. They are famous for their powers of geographic concentration. Their rapid ascent creates in a few thousand vertical feet what, spread horizontally, would require a few thousand miles to replicate. Here, density replaces expansiveness. One can see across a hundred miles of sky, and into half a continent of ecosystems. It is possible to traverse from desert grassland to alpine krumholtz almost instantly.

They are equally renown for their isolation, not only from the land surrounding them but from one another. The peaks array like stepping stones between the Sierra Madre Occidental and the Colorado Plateau; here, North America has pulled apart and the land has fallen between flanking subcontinental plateaus like a collapsed arch, leaving a jumble of basins and ranges as jagged mountains to poke through the rubble. The degree of geographic insularity is striking: they are mountain islands amid seas of desert and semi-arid grasslands. On some peaks relict species survive from the Pleistocene; on others, new subspecies appear. No peak has everything the others do. A Neoarctic biota mixes with a Neotropical one, black bear with jaguar, Steller’s jay with thick-beaked parrot. The Pinaleños have Engleman spruce. Mount Graham boasts a red squirrel. The Pedragosas grow Apache pine. The Peloncillos are messy with overgrowth and dense litter; the Huachucas, breezy with oak savannas. The Madrean Archipelago displays the general with the distinct: unique variations amid a common climate. They can serve as a textbook example of island biogeography. That observation extends to their fires as well. …

The Forest Health Crisis: How Did We Get In This Mess?

Charles E. Kay. 2009. The Forest Health Crisis: How Did We Get In This Mess? Mule Deer Foundation Magazine No.26:14-21.

Dr. Charles E. Kay, Ph.D. Wildlife Ecology, Utah State University, is the author/editor of Wilderness and Political Ecology: Aboriginal Influences and the Original State of Nature [here], author of Are Lightning Fires Unnatural? A Comparison of Aboriginal and Lightning Ignition Rates in the United States [here], co-author of Native American influences on the development of forest ecosystems [here], and numerous other scientific papers.

Full text with photos (click on photos for larger images):

THE WEST is ablaze! Every summer large-scale, high-intensity crown fires tear through our public lands at ever increasing and unheard of rates. Our forests are also under attack by insects and disease. According to the national media and environmental groups, climate change is the villain in the present Forest Health Crisis and increasing temperatures, lack of moisture, and abnormally high winds are to blame. Unfortunately, nothing could be further from the truth.

The Sahara Desert, for instance, is hot, dry, and the wind blows, but the Sahara does not burn. Why? Because there are no fuels. Without fuel there is no fire. Period, end of story, and without thick forests there are no high-intensity crown fires. Might not the real problem then be that we have too many trees and too much fuel in our forests? The Canadians, for instance, have forest problems similar to ours but they do not call it a “Forest Health Crisis,” instead they call it a Forest Ingrowth Problem. The Canadians have correctly identified the issue, while we in the States have not. That is to say, the problem is too many trees and gross mismanagement by land management agencies, as well as outdated views of what is natural.

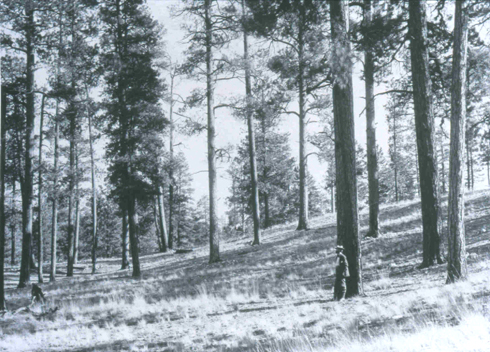

When Europeans first arrived in the West, ponderosa pine forests were open and park-like. You could ride everywhere on horseback or even in a horse and buggy, the forests were so open. On average there were only between 10 and 40 trees per acre with an understory of grasses, forbs, and shrubs. Extensive meadows were also common. In short, ideal mule dear habitat.

Photo 1 — A 1905 photograph of a ponderosa pine forest on the Kaibab in northern Arizona. It is amazing how parklike our pine forests once were. The forests were so open that you could travel virtually anywhere in a horse and buggy. Understory grasses, forbs, and shrubs were abundant. U.S. Geological Survey photo.

Photo 2 — A 1903 photograph of a ponderosa pine forest on the Coconino in northern Arizona. Note the park-like conditions and the men for scale, as well as the abundance of understory forage. Due to the openness of the forest, historically, crown fires never occurred, unlike conditions today. U.S. Forest Service photo.

Today, however, those same forests contain anywhere from 500 to 2,000 mostly smaller trees per acre. Travel on horseback is out of the question, and access by foot is even difficult. Many former meadows are now overgrown with trees. Understory forage production is approaching zero and our pine forests are becoming increasingly worthless as mule deer habitat.