Traditional and local ecological knowledge about forest biodiversity in the Pacific Northwest

Charnley, Susan; Fischer, A. Paige; Jones, Eric T. 2008. Traditional and local ecological knowledge about forest biodiversity in the Pacific Northwest. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-751. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 52 p.+

Full text [here]

Abstract

This paper synthesizes the existing literature about traditional and local ecological knowledge relating to biodiversity in Pacific Northwest forests in order to assess what is needed to apply this knowledge to forest biodiversity conservation efforts. We address four topics: (1) views and values people have relating to biodiversity, (2) the resource use and management practices of local forest users and their effects on biodiversity, (3) methods and models for integrating traditional and local ecological knowledge into biodiversity conservation on public and private lands, and (4) challenges to applying traditional and local ecological knowledge for biodiversity conservation. We focus on the ecological knowledge of three groups who inhabit the region: American Indians, family forest owners, and commercial nontimber forest product (NTFP) harvesters.

Integrating traditional and local ecological knowledge into forest biodiversity conservation is most likely to be successful if the knowledge holders are directly engaged with forest managers and western scientists in on-the-ground projects in which interaction and knowledge sharing occur. Three things important to the success of such efforts are understanding the communication styles of knowledge holders, establishing a foundation of trust to work from, and identifying mutual benefits from knowledge sharing that create an incentive to collaborate for biodiversity conservation. Although several promising models exist for how to integrate traditional and local ecological knowledge [TEK and LEK] into forest management, a number of social, economic, and policy constraints have prevented this knowledge from flourishing and being applied. These constraints should be addressed alongside any strategy for knowledge integration.

Keywords: Traditional ecological knowledge, forest management, biodiversity conservation, American Indians, family forest owners, nontimber forest product harvesters, Pacific Northwest.

The Market Illiteracy Embodied in the Politically Correct Version of Sustainability

Travis Cork III. 2010. The Market Illiteracy Embodied in the Politically Correct Version of Sustainability. W.I.S.E. White Paper No. 2010-4

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

The forest products industry has been practicing sustainable forestry for much of the Twentieth Century. During this time we have seen substantial gains in the management and utilization of forests, particularly on forest industry lands. “Although the forest industry occupies only about one-seventh of total U. S. timberland, its land produces a full fifth of national timber growth, a quarter of the growth of softwoods, and about a third of the annual timber harvest.” 1/

The forest industry has signed on to the sustainable forestry initiative, no doubt for public relations, but it does not need market illiterate bureaucrats and GAGs (green advocacy groups-The Nature Conservancy, Sierra Club, et al.) telling it how to practice sustainable forestry. …

Depletion is not caused by lack of resources, but by a lack of institutions, specifically private property rights and free-markets, that allow for a rational and sustained use of resources. In America, it is a manufactured crisis. If depletion of forest resources were a real problem, the responsible solution would be to find ways to increase productivity. Locking up more of the American land base (50 percent or more with Reed Noss’ Wildlands Project) and restricting utilization on remaining lands is neither a serious nor an ethical approach to depletion. But then the crisis-mongers are not concerned about the depletion of resources but the control of resources.

A statist perspective of sustainability

Sustainability is defined as

meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

The American Forest & Paper Association expands this to include forestry.

Sustainable forestry means managing our forests to meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs by practicing a land stewardship ethic which integrates the growing, nurturing, and harvesting of trees for useful products with the conservation of soil, air and water quality, and wildlife and fish habitat.

What bureaucrat or academic can make an accurate measurement of my “sustainable” allotment of forest resources (or any other resource) in quantifiable terms; e.g., cords, tons, board feet, cubic meters, kilograms, etc.?

Who is the soothsayer, seer, or mystic that can divine what future generations will want from the forest or any resource?

Who can determine the annual removal of wood products or any resource compared to the volume estimated to be sustainable?

The answer is no one.

History tells us “no exhaustible resource is essential or irreplaceable… The relevant resource base is defined by knowledge, rather than by physical deposits of existing resources.” 7/ Unless suppressed by government force, human intelligence and ingenuity break the bonds that carrying capacity imposes on other species. …

Sustainability, as defined, is vague and inoperable highfalutin rhetoric. It is evidence that the natural resource community, at least in the public sector, academia, and some corporate boardrooms, is ignorant of market economics and responsible social behavior. This ignorance puts the productive future of the forest resources sector very much at risk.

Ecological Science as a Creation Story

Robert H. Nelson. 2010. Ecological Science as a Creation Story. The Independent Review, v. 14, n. 4, Spring 2010.

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

SINCE at least the late 1980s, environmental writers have made growing use of the explicit Christian language of “the Creation.” Two 1990s books by environmental authors, for example, are Caring for Creation (Oelschlaeger 1994) and Covenant for a New Creation ( Robb and Casebolt 1991). The magazine of the Natural Resources Defense Council describes the need for a greater “spiritual bond between ourselves and the natural world similar to God’s covenant with creation” (Borelli 1988). Natural environments isolated historically from European contact are commonly described as having once been an “Eden” or a “paradise” on the earth — similar to the Creation before the fall (McCormick 1989; “Inside the World’s Last Eden” 1992).

Such creationist language has also invaded mainstream environmental politics. During his tenure as vice president, Al Gore said that we must cease “heaping contempt on God’s creation” (qtd. in Niebuhr 1993). In a 1995 speech remarkable for its religious candor, Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt said that “our covenant” requires that we “protect the whole of Creation.” Invoking messages reminiscent of John Muir, Babbitt argued that wild areas are a source of our core “values” because they are “a manifestation of the presence of our Creator.” It is necessary to protect every animal and plant species, Babbitt said, because “the earth is a sacred precinct, designed by and for the purposes of the Creator,” and thus we can learn about God by encountering and experiencing his creation.

The American environmental movement has deep roots in and still depends heavily on the conviction that a person finds a mirror of God’s thinking in the encounter with wild nature — or, in traditional Christian terms, that a person is in the presence of “the Creation.” Absent this conviction, many of the American environmental movement’s basic beliefs and important parts of its policy agenda would be difficult to explain and defend.[1] The use of creation language also reflects an increased role that the institutional churches of Christianity are now playing in the environmental movement. This involvement has worked to narrow the previously large linguistic gap between traditional Christian creationism and what might be called a secular “environmental creationism”- the use of creationist language without the explicit Christian context. …

The Fictional Ecosystem and the Pseudo-science of Ecosystem Management

Travis Cork III. 2010. The Fictional Ecosystem and the Pseudo-science of Ecosystem Management. W.I.S.E. White Paper No. 2010-3, Western Institute for Study of the Environment.

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

LAND USE CONTROL has long been the goal of the statist element in our society. Zoning was the first major attempt at land use control. Wetland regulation and the Endangered Species Act have extended some control, but nothing has yet brought about a general policy of land use control. Ecosystem management is an attempt to achieve that end.

The fictional ecosystem

In The Use and Abuse of Vegetational Concepts and Terms, A. G. Tansley coined the term “ecosystem.” Tansley rejected the “conception of the biotic community” and application of the “terms ‘organism’ or ‘complex organism’” to vegetation. “Though the organism may claim our primary interest, when we are trying to think fundamentally we cannot separate them from their special environment, with which they form one physical system. It is the systems so formed which, from the point of view of the ecologist, are the basic units of nature on the face of the earth. … These ecosystems, as we may call them, are of the most various kinds and sizes… which range from the universe as a whole down to the atom” 1/

Tansley further writes “[e]cosystems are extremely vulnerable, both on account of their own unstable components and because they are very liable to invasion by the components of other systems. … This relative instability of the ecosystem, due to the imperfections of its equilibrium, is of all degrees of magnitude. … Many systems (represented by vegetative climaxes) which appear to be stable during the period for which they have been under accurate observation may in reality have been slowly changing all the time, because the changes effected have been too slight to be noticed by observers.” 2/

Lackey confirms writing “[t]here is no ‘natural’ state in nature; it is a relative concept. The only thing natural is change, some-times somewhat predictable, oftentimes random, or at least unpredictable. It would be nice if it were otherwise, but it is not.” 3/

The ecosystem may be the basic unit of nature to the ecologist, that is—man, but it is not the basic unit to nature. Its proponents confirm that it is a man-made construct.

We are told in Creating a Forestry for the 21st Century: The Science of Ecosystem Management that “ecosystems, in contrast to forest stands, typically have been more conceptual than real physical entities.” 4/

The Report of the Ecological Society of America Committee on the Scientific Basis for Ecosystem Management tells us “[n]ature has not provided us with a natural system of ecosystem classification or rigid guidelines for boundary demarcation. Ecological systems vary continuously along complex gradients in space and are constantly changing through time.” 5/

“People designate ecosystem boundaries to address specific problems, and therefore an ecosystem can be as small as the surface of a leaf or as large as the entire planet and beyond.” 6/

“Defining ecosystem boundaries in a dynamic world is at best an inexact art,” says the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) in its 1995 publication, Integrating Social Science and Ecosystem Management: A National Challenge.

“Among ecologists willing to draw any lines between ecosystems, no two are likely to draw the same ones. Even if two agree, they would recognize the artificiality of their effort…” 7/ …

Mistreatment of the economic impacts of extreme events in the Stern Review Report on the Economics of Climate Change

Roger Pielke Jr. 2007. Mistreatment of the economic impacts of extreme events in the Stern Review Report on the Economics of Climate Change. Global Environmental Change 17 (2007) 302–310.

Roger Pielke Jr. is a Fellow of the Center for Science and Technology Policy Research, University of Colorado.

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

Abstract

The Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change has focused debate on the costs and benefits of alternative courses of action on climate change. This refocusing has helped to move debate away from science of the climate system and on to issues of policy. However, a careful examination of the Stern Review’s treatment of the economics of extreme events in developed countries, such as floods and tropical cyclones, shows that the report is selective in its presentation of relevant impact studies and repeats a common error in impacts studies by confusing sensitivity analyses with projections of future impacts. The Stern Review’s treatment of extreme events is misleading because it overestimates the future costs of extreme weather events in developed countries by an order of magnitude. Because the Stern Report extends these findings globally, the overestimate propagates through the report’s estimate of future global losses. When extreme events are viewed more comprehensively the resulting perspective can be used to expand the scope of choice available to decision makers seeking to grapple with future disasters in the context of climate change. In particular, a more comprehensive analysis underscores the importance of adaptation in any comprehensive portfolio of responses to climate change.

Introduction: exploiting an excess of objectivity

In a provocative article titled “How Science Makes Environmental Controversies Worse” Daniel Sarewitz explains that scientific research results in an “excess of objectivity” in political debates (Sarewitz, 2004). What he means with this phrase is that in most (if not all) cases of political conflict involving science, available research is sufficiently diverse so as to provide a robust resource for political advocates to start with a conclusion and then selectively pick and choose among existing scientific studies to buttress their case. Simply put, to cherry pick, to take the best leave the rest. …

Rhymes With Chiricahua.

Stephen J. Pyne. 2009. Rhymes With Chiricahua. Copyright 2009 Stephen J. Pyne

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

While the Chiricahua Mountains are famous for many reasons to many groups, they are rarely known for their fires. They should be. Some start from lightning, some from ranchers. Some are set by rangers, or are allowed some room to roam by them. Some are left by transients in the person of hunters, campers, and hikers. In recent years more are associated with traffic across the border with Mexico. The Chiricahuas have, at the moment, less of this than other border-hugging districts within the Coronado National Forest, but fires to distract, fires to hide, and fires abandoned by illegal border-crossers are becoming more prominent. All in all, it’s an interesting medley.

Mark Twain once observed that history doesn’t repeat itself but it sometimes rhymes. These days it seems there is a lot of rhyming in the Chiricahuas as fires echo a fabled but assumed vanished past. This revival moves the Chiricahuas, among the most isolated of mountain ranges, a borderland setting for fire as for other matters, close to the core of contemporary thinking about managing fire in public wildlands.

The Chiricahuas –- actually a giant, deeply eroded and flank-gouged massif –- are among the southernmost of America’s Sky Islands, compact mountain ranges that both cluster and stand apart from one another, like an archipelago of volcanic isles. They are famous for their powers of geographic concentration. Their rapid ascent creates in a few thousand vertical feet what, spread horizontally, would require a few thousand miles to replicate. Here, density replaces expansiveness. One can see across a hundred miles of sky, and into half a continent of ecosystems. It is possible to traverse from desert grassland to alpine krumholtz almost instantly.

They are equally renown for their isolation, not only from the land surrounding them but from one another. The peaks array like stepping stones between the Sierra Madre Occidental and the Colorado Plateau; here, North America has pulled apart and the land has fallen between flanking subcontinental plateaus like a collapsed arch, leaving a jumble of basins and ranges as jagged mountains to poke through the rubble. The degree of geographic insularity is striking: they are mountain islands amid seas of desert and semi-arid grasslands. On some peaks relict species survive from the Pleistocene; on others, new subspecies appear. No peak has everything the others do. A Neoarctic biota mixes with a Neotropical one, black bear with jaguar, Steller’s jay with thick-beaked parrot. The Pinaleños have Engleman spruce. Mount Graham boasts a red squirrel. The Pedragosas grow Apache pine. The Peloncillos are messy with overgrowth and dense litter; the Huachucas, breezy with oak savannas. The Madrean Archipelago displays the general with the distinct: unique variations amid a common climate. They can serve as a textbook example of island biogeography. That observation extends to their fires as well. …

The Forest Health Crisis: How Did We Get In This Mess?

Charles E. Kay. 2009. The Forest Health Crisis: How Did We Get In This Mess? Mule Deer Foundation Magazine No.26:14-21.

Dr. Charles E. Kay, Ph.D. Wildlife Ecology, Utah State University, is the author/editor of Wilderness and Political Ecology: Aboriginal Influences and the Original State of Nature [here], author of Are Lightning Fires Unnatural? A Comparison of Aboriginal and Lightning Ignition Rates in the United States [here], co-author of Native American influences on the development of forest ecosystems [here], and numerous other scientific papers.

Full text with photos (click on photos for larger images):

THE WEST is ablaze! Every summer large-scale, high-intensity crown fires tear through our public lands at ever increasing and unheard of rates. Our forests are also under attack by insects and disease. According to the national media and environmental groups, climate change is the villain in the present Forest Health Crisis and increasing temperatures, lack of moisture, and abnormally high winds are to blame. Unfortunately, nothing could be further from the truth.

The Sahara Desert, for instance, is hot, dry, and the wind blows, but the Sahara does not burn. Why? Because there are no fuels. Without fuel there is no fire. Period, end of story, and without thick forests there are no high-intensity crown fires. Might not the real problem then be that we have too many trees and too much fuel in our forests? The Canadians, for instance, have forest problems similar to ours but they do not call it a “Forest Health Crisis,” instead they call it a Forest Ingrowth Problem. The Canadians have correctly identified the issue, while we in the States have not. That is to say, the problem is too many trees and gross mismanagement by land management agencies, as well as outdated views of what is natural.

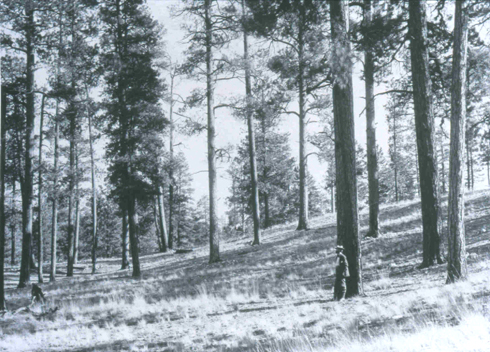

When Europeans first arrived in the West, ponderosa pine forests were open and park-like. You could ride everywhere on horseback or even in a horse and buggy, the forests were so open. On average there were only between 10 and 40 trees per acre with an understory of grasses, forbs, and shrubs. Extensive meadows were also common. In short, ideal mule dear habitat.

Photo 1 — A 1905 photograph of a ponderosa pine forest on the Kaibab in northern Arizona. It is amazing how parklike our pine forests once were. The forests were so open that you could travel virtually anywhere in a horse and buggy. Understory grasses, forbs, and shrubs were abundant. U.S. Geological Survey photo.

Photo 2 — A 1903 photograph of a ponderosa pine forest on the Coconino in northern Arizona. Note the park-like conditions and the men for scale, as well as the abundance of understory forage. Due to the openness of the forest, historically, crown fires never occurred, unlike conditions today. U.S. Forest Service photo.

Today, however, those same forests contain anywhere from 500 to 2,000 mostly smaller trees per acre. Travel on horseback is out of the question, and access by foot is even difficult. Many former meadows are now overgrown with trees. Understory forage production is approaching zero and our pine forests are becoming increasingly worthless as mule deer habitat.

The Wildland/Science Interface

Stephen J. Pyne. 2009. The Wildland/Science Interface. Copyright 2009 Stephen J. Pyne

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

A long narrow road winds steeply up into thickly-wooded backcountry to an exclusive enclave of costly structures, all well beyond the periphery of settlement. It’s the formula for the worstcase scenario of the wildland/urban interface, except that this is no subprime landscape stuffed with trophy homes. It’s a telescope complex atop Mount Graham, and on the Sky Islands of Arizona the scene is repeated four times. Call it the wildland/science interface.

Fire management accepts as axiomatic that it is science-based or at least science-informed and that good science is the antidote to the toxins of politics, land development, and a Smokey-blinkered populace that doesn’t understand the natural ecology and inevitability of fire. Science is better than experience or history, and more science is better still. Science, preferably natural science, since even social science is tainted with the implied values of its human doers, is the solution. At Mount Graham, however, it is the problem. And the challenge is not simply that “science” here underwrites its own version of the WUI and opens paved roads to remote sites that complicate fire management and compromise biodiversity. The real challenge is the assumption that science stands apart from the scene it describes and from its Olympian perch can peer objectively outward and advise wisely.

The Mount Graham International Observatory suggests instead, that science’s lofty perch is not removed from land management and that science, too, has its self-interests that can influence what it sees, does, and says. Science, in brief, is not an ungrounded platform for viewing the universe of fire and recording its observations. It is sited, and that siting determines what it sees, and decisions over such sites make science and its caste of practitioners as motivated by their own values and ambitions as loggers, ranchers, real estate developers, and ATV recreationists. Science has its own dynamic apart from nature, its own presence on the land, and its own politics. The 1.83 meter primary mirror of the VATT telescope, while nominally looking out, is also a reflecting lens that looks back on its viewers.

Fire Gods and Federal Policy

Thomas M. Bonnicksen, Ph.D. 1989. Fire Gods and Federal Policy. American Forests 95(7 & 8): 14-16, 66-68.

Full text:

THE ISSUE I am presenting is based on a summary of both the letter I sent to the Interagency Fire Management Policy Review Team and testimony I presented to a joint committee of Congress in January of 1989 on the Yellowstone wildfire problem. The issue is how to restore naturalness to park and wilderness areas while preventing such wildfires from occurring again. I will concentrate on the “let nature takes its course” philosophy that led to the Yellowstone fires. I will also provide a scientifically sound and responsible approach to resource management. My purpose is to encourage the use of scientific management in national park and wilderness areas.

I was critical of the Park Service fire management program when it started. I was a ranger-naturalist at Kings Canyon National Park where the program began. At that time, I wrote a white paper that pointed out the flaws in the fire management program and the entire ranger-naturalist staff agreed with my conclusions and signed the paper. This was the first documented internal Park Service critique of the fire management program. The points that we made so many years ago are still true today, only now the problem has grown worse and it has taken on a more ominous dimension with the Yellowstone wildfires.

I have been conducting research, publishing and speaking on fire management and restoration ecology in national park and wilderness areas for twenty years. Most of my research addressed the management of giant sequoia-mixed conifer forests in the Sierra Nevada. I also investigated the effects of the Yellowstone wildfires for members of Congress. After giving so much thought to this issue over so many years, I am convinced that the real problem is the lack of clear objectives for the management of national park and wilderness areas.

The wildfires that swept through Yellowstone and surrounding wilderness areas during the summer of 1988 were not a natural event. Unlike the eruption of Mount St. Helens (which could not be controlled) the number, size and destructiveness of the Yellowstone wildfires could have been substantially reduced. The changes that took place in the vegetation mosaic and fuels in Yellowstone during nearly a century of fire suppression were preventable and reversible. The Park Service was aware of the risks of letting lightning fires burn, especially during a drought. Mr. Howard T. Nichols, a Park Service Environmental Specialist sent to help in the command center during the Yellowstone wildfires, stated in an internal memo that members of the Yellowstone staff knew “that 1988 was a very dry year” yet they “were determined to maintain the Park’s natural fire regime.” Thus the Yellowstone wildfires were caused by a combination of decades of neglect and incredibly poor judgment.

Dr. James K. Brown, a Forest Service scientist, stated in a paper he delivered to the American Association for the Advancement of Science in January of 1989 that, assuming a prescribed burning program was initiated in 1972, “threats to villages may have been prevented or greatly reduced.” Dr. Brown also stated “a program of manager ignited prescribed burning in subalpine forests such as lodgepole pine” is “feasible.” In an earlier paper presented at the Wilderness Fire Symposium in Missoula, Montana, in 1983, Dr. Brown also said that “To manage for a natural role of fire, planned ignitions, in my view, are necessary to deal with fuels and topography that have high potential for fire to escape established boundaries.” Thus, it is likely that the wildfires would not have reached the mammoth size of 1.4 million acres if only a fraction of the hundreds of millions of dollars used to fight the Yellowstone wildfires had been spent on scientific management that utilized prescribed burning, especially if vigorous suppression efforts had been undertaken by the Park Service when each fire began.

People of the Prairie, People of the Fire

Stephen Pyne. 2009. People of the Prairie, People of the Fire. The Wildland Fire Lessons Learned Center.

*****

Dr. Stephen J. Pyne is Regents Professor at Arizona State University. He is author of Awful Splendour: A Fire History of Canada (2007) Univ. British Columbia Press, Fire in America: A Cultural History of Wildland and Rural Fire (1982), Burning Bush: A Fire History of Australia (1991), World Fire: The Culture of Fire on Earth (1995), Vestal Fire: An Environmental History, Told Through Fire, of Europe and Europe’s Encounter with the World (1997), The Ice: A Journey to Antarctica (1986), and numerous other histories, memoirs, essays, and texts about fire.

This essay is one of three related essays about fire in the Midwest. The others are:

Missouri Compromise [here], and

Patch Burning [here]

*****

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

Twice over the past 20,000 years the Illinois landscape has been destroyed and rebuilt. In the first age the agent of change was ice, mounded into sheets and leveraged outward through a suite of periglacial processes from katabatic winds to ice-dam-breaching torrents. The ice obliterated everything, leaving as its legacy a geomorphic matrix of dunes, swales, moraines, loess, great lakes and landscape-dissecting streams.

For the second, the agent was iron, forged into plows and then into rails. Coal replaced climate as a motive force, and people pushed aside the planetary rhythms of Milankovitch cycles and cosmogenic carbon cycles as a prime mover. They left behind a surveyed landscape of squared townships.

The first event worked through a geologic matrix; the second, a biological one; and they were equally thorough. All the state went under ice at least once; the last outpouring, the Wisconsin glaciation, pushed south from Lake Michigan and covered perhaps a third. The frontier of agricultural conversion put nearly all of the state to the plow, or where rocky moraines prevented it, to the hoofs of livestock. When it ended, only one-tenth of one percent of the precontact landscape remained more or less intact. Less than one acre out of a thousand held its founding character, and that acre was itself minced into a thousand, scattered pieces.

In both ice age and iron age, however, life revived after the extinction with fire as an informing presence – fire in the hands of people. The biological recolonization of the landscape after the ice had fire in its mix and expressed itself as oak savannas, tallgrass prairies, and grassy wetlands, stirred by routine burning. Fire was a universal catalyst; in particular, prairie and fire became ecological symbionts. The reconstruction of the second landscape has relied on industrial combustion, fueled by the fossil fallow of biomass.

But those intent on sparing, or actively restoring, the former landscape must appeal to open burning. A fire sublimated through a tractor does not yield the same effects as one let loose to free-burn through big bluestem. The regeneration of such settings is troubling –- unstable and scattered, an inchoate genesis still in the making, its reliance on fire both essential and challenged.