Traditional and local ecological knowledge about forest biodiversity in the Pacific Northwest

Charnley, Susan; Fischer, A. Paige; Jones, Eric T. 2008. Traditional and local ecological knowledge about forest biodiversity in the Pacific Northwest. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-751. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 52 p.+

Full text [here]

Abstract

This paper synthesizes the existing literature about traditional and local ecological knowledge relating to biodiversity in Pacific Northwest forests in order to assess what is needed to apply this knowledge to forest biodiversity conservation efforts. We address four topics: (1) views and values people have relating to biodiversity, (2) the resource use and management practices of local forest users and their effects on biodiversity, (3) methods and models for integrating traditional and local ecological knowledge into biodiversity conservation on public and private lands, and (4) challenges to applying traditional and local ecological knowledge for biodiversity conservation. We focus on the ecological knowledge of three groups who inhabit the region: American Indians, family forest owners, and commercial nontimber forest product (NTFP) harvesters.

Integrating traditional and local ecological knowledge into forest biodiversity conservation is most likely to be successful if the knowledge holders are directly engaged with forest managers and western scientists in on-the-ground projects in which interaction and knowledge sharing occur. Three things important to the success of such efforts are understanding the communication styles of knowledge holders, establishing a foundation of trust to work from, and identifying mutual benefits from knowledge sharing that create an incentive to collaborate for biodiversity conservation. Although several promising models exist for how to integrate traditional and local ecological knowledge [TEK and LEK] into forest management, a number of social, economic, and policy constraints have prevented this knowledge from flourishing and being applied. These constraints should be addressed alongside any strategy for knowledge integration.

Keywords: Traditional ecological knowledge, forest management, biodiversity conservation, American Indians, family forest owners, nontimber forest product harvesters, Pacific Northwest.

The Evils of Pinyon and Juniper

Charles E. Kay. 2010. The Evils of Pinyon and Juniper. Mule Deer Foundation Magazine Vol 10(5): 6-13

Dr. Charles E. Kay, Ph.D. Wildlife Ecology, Utah State University, is the author/editor of Wilderness and Political Ecology: Aboriginal Influences and the Original State of Nature [here], author of Are Lightning Fires Unnatural? A Comparison of Aboriginal and Lightning Ignition Rates in the United States [here], co-author of Native American influences on the development of forest ecosystems [here], and numerous other scientific papers.

Full text with photos (click on photos for larger images):

PINYON PINES and upright junipers are found throughout the West. Ash and red berry juniper occur in Texas, while western juniper is most abundant in the interior Pacific Northwest. One-seeded and Utah juniper are widespread in Nevada, Utah, and on the Colorado Plateau, whereas Rocky Mountain juniper can be found in Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming. All junipers have small, scale-like leaves and are often called cedars due to their aromatic wood. In fact, the most widely occurring juniper in the East is known as eastern red cedar. In addition to the tall, or upright junipers, there are a few, low-growing species of which horizontal and common are the mostly likely to be encountered.

Pinyons, on the other hand, are represented by only two species. Single-leaf pinyon has only one needle per fascicle, while two-needle pinyon has two needles per fascicle or bundle. Pinyons are abundant in Nevada, Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico. Pinyons and junipers are the most drought tolerant of all western conifers. In addition, pinyons and junipers are chemically defended by terpenes and other compounds that inhibit ruminant microbial digestion. Livestock will generally not consume pinyon or juniper and mule deer will generally browse juniper only if the animals are starving. Pinyons and most junipers are also extremely invasive.

Prior to European settlement, it has been estimated that pinyon and juniper covered 7.5 million acres in the West, while today P-J has infested over 75,000,000 acres, a ten-fold increase. Moreover, the number of trees per acre has increased 10 to 100 fold. I have compiled 1,879 repeat photosets in southern Utah and of that total, 1,007 photo pairs depict pinyon and/or juniper. In 96% of those cases, P-J increased, often dramatically. As pinyon and juniper have expanded their range and thickened, the production of shrubs, forbs, and grasses has declined precipitously. In many stands, understory forage production is near zero, and as understory species decrease, soil erosion increases, even on ungrazed sites. In New Mexico’s Bandelier National Monument, for instance, as pinyon and juniper have thickened, understory species have been eliminated, which has lead to a drastic increase in soil erosion threatening the park’s archaeological sites.

Closed-canopy stands of pinyon-juniper are rare in early historical photographs. Instead, most stands once consisted of a few widely-spaced pinyon and/or juniper with abundant grasses, shrubs, and forbs in what could be characterized as a savanna. With time, however, those stands have infilled until today many pinyon-juniper sites have a closed canopy. Pinyon and juniper have also extended their range by invading grasslands, sagebrush, and other plant communities. Historically, old-growth pinyon-juniper was restricted to rocky outcroppings, areas with poor soils, and other fire refugia. Crown-fire behavior in pinyon-juniper is increasingly common in the West today, but there is no evidence that was the norm prior to European settlement and the expansion and infilling of pinyon-juniper woodlands. Only 3 or 1,007 historical photos taken in southern Utah show any evidence of stand-replacing fire in pinyon-juniper until modern times. The same is true in other areas.

Baden-Powell and Australian Bushfire Policy: Part 2

By Roger Underwood

Editor’s Notes: This essay is one of a series (circulated to colleagues on the Internet, but unpublished) which examines reports, letters, stories and anecdotes from early volumes of The Indian Forester, the principal forestry journal of India since 1880.

It is the second to deal with Baden Baden-Powell. The first is [here].

Baden Henry Baden-Powell (1841-1901) entered the Bengal Civil Service at the age age of 20 and eventually became a Judge of the Chief Court of the Punjab and India’s first Inspector-General of Forests. He was among the first to bring European forestry to India. B. H. Baden-Powell was the son of Rev. Baden Powell (1796–1860), an English mathematician and Church of England priest, and brother of Robert Baden-Powell (1857-1941), the founder of the Boy Scouts.

Author Roger Underwood is a former General Manager of the Department of Conservation and Land Management (CALM) in Western Australia, a regional and district manager, a research manager and bushfire specialist. Roger currently directs a consultancy practice with a focus on bushfire management and is Chairman of The Bushfire Front Inc.. He lives in Perth, Western Australia.

Baden-Powell and Australian bushfire policy: Part 2

By Roger Underwood

In an earlier paper on this issue [1] I discussed the profound influence of 19th century Indian colonial foresters on the development of bushfire policy in Australia and (indirectly) in the United States. The first senior foresters of the Indian Forest Service, men like Baden Baden-Powell, Dietrich Brandis, William Schlich and David Hutchins, were German, French or English-trained, and were wonderful pioneering foresters, but they had little practical understanding of fire behaviour or fire ecology and they were imbued with the desire to stock-up every acre of forest with commercial trees. Fire was seen as the principal enemy to this policy, and as an enemy to be ruthlessly expunged from the face of British India.

The imperial view on fire was not shared by the indigenous population, who had been using fire as a land management tool for perhaps thousands of years. There were also opposing views within the forestry profession, and some of these found voice at conferences of forest officers, or in published papers. A good example is the work of M. J. Slym a forest officer working in the Salween Division of British Burma in the 1870s. Slym presented a paper, entitled Memorandum on Jungle Fires, at a Forest Conference at Rangoon in 1875. The paper was subsequently published in The Indian Forester two years later [2].

Slym’s paper, which focuses on the monsoonal rainforest in which the principal timber tree is teak (Tectona grandis) addresses what he describes as

… the general belief among forest officers that fires do a great deal of harm.

but he points out that this view is not universally held, nor does it reflect the views of the native populace who have lived in and around the forest for centuries. He summarises the opposing views as follows: “while many have pronounced that [the effects of fire] upon the forests to be unqualifiedly injurious and that they must be prevented at any cost, others believe they act favourably towards [the forest].”

Both positions are deficient in Slym’s opinion; the first view “does not show how fires could be suppressed without doing harm in some other direction” while the second fails to “disclose how fires act favourably” towards the forest.

The causes of jungle fires in Slym’s district in Burma were many and varied. There were the inevitable “escapes from camp fires” a fire cause that still figured prominently in bushfire statistics in the jarrah forest when I was a young forester, but other causes are more exotic, for example, fires lit to drive game for hunting, to clear jungle pathways of snakes and to keep tigers at a safe distance from villages.

Of great interest to me was that Slym also lists as one of the main causes of forest fires

… the tradition of the hill people that burning the forest has a salutary effect.

This belief is

… kept alive by [their] actual experience of the increased healthfulness of the districts after fires.

This is a close parallel with the well-documented use of fire by Australian Aboriginal people for the purpose of “cleaning up the country”.

Slym then takes up, one by one, all of the standard arguments used to justify the banning of fire from the forest. It is claimed, he reports, that fires destroy seed, kill seedlings, char the stems of mature trees allowing access for insects, destroy the humus and impoverish the soil. Each of these he deals with in turn, systematically proving the fears to be groundless or requiring qualification, and basing his position on personal experience and observations in the forest. In particular he draws attention to what would later be called by Australian foresters “the ashbed effect” – that is, the increase in soil fertility arising from increased nutrient availability after a fire. “Many a forester” he adds “will have noticed the fine teak seedlings that spring up from almost every burnt heap and near every burnt log of wood.”

Modern Australian bushfire managers would applaud Slym’s understanding of the two most fundamental aspects of forest fire management: first, that fires cannot be prevented; and second, that fire damage is related to fire intensity. He does not advocate widescale annual burning, but rather a well-managed firing of the bush that is integrated with other management demands for the purposes both of minimising wildfire damage, and promoting forest health.

Eventually he concludes:

The collective inference I draw, is that [fires] should not be prevented entirely, but the strength of them sufficiently lessened to lessen their harm. This can only be affected by firing the forest ourselves…commencing early [in the dry season].

He goes on to say that in his opinion, the forest should be burned

… at an interval before the leaves accumulate, thus preventing a fire that harms the forest.

It is almost as if he is writing about bushfire management in the Australian eucalypt forests in modern times, so precisely does this view coincide with contemporary enlightened philosophies [3].

Furthermore, Slym concludes that the ideal of fire exclusion as promoted by the senior brass of the Indian Forest Service at that time has costs that do not outweigh the benefits.

[Fire exclusion] is all but impractical, and at best dangerous, as it may, as already has been shown, drive teak out altogether [4].

Again I hear the voices of modern fire ecologists, speaking of species that decline and eventually disappear in bushland where fire has long been un-naturally excluded.

Slym was familiar with the long-held burning practices of the Burmese hill people, and was close enough to it to enable him to see the way it was done, as well as its impacts. It is obvious from his conclusions that he understood the relationships between fuel levels, fire intensity and fire damage – concepts that are still not understood by many Australian academics today – and of the need to integrate fire management with other objectives, in his case timber production and regeneration. The silvicultural system adopted for teak forest by the Indian Forest Service was a selection system using a prescribed girth limit restriction which ensured the retention of growing stock, and allowed natural regeneration. This operated with great success for generations, something that could only be achieved through close attention to fire management at the same time [5].

There is another echo of modern times in the denouement of this story. Slym’s paper to the Rangoon conference was so unpopular with the senior staff of the Forest Service, that it was omitted from the published conference proceedings. Slym was told by the Conference President (presumably Dietrich Brandis, the Inspector-General of the Indian Forest Service at the time) that his paper “could not be recorded, neither could the reason for not doing so be mentioned”. Luckily for posterity the editor of The Indian Forester took a different view and agreed to publish it, although this may have been done provocatively, as later editions of the journal contained letters from correspondents who disagreed with Slym’s views [6].

The muzzling of voices critical of government policy was not, of course, and is not restricted to British India. I can remember when I started work as a forest officer in Western Australia in 1962 being briefed on the fact that there was a clause in the Public Service Act forbidding any government officer from voicing criticism of any government policy; severe penalties would apply to a transgressor [7]. As far as I am aware this rule persists to this day.

I am also reminded that a similar form of censorship operates in some scientific journals today, where editorial panels control what is, and what is not published according to whether or not it fits with the panel’s stance on issues such as fire or global warming. Slym’s paper would be very unlikely to appear today in, for instance, the journal of the Australian Ecological Society, or the lamentable Journal of Wildland Fire.

A direct line of descent to early Australian bushfire policy can be traced from the concepts espoused by Baden-Powell and his contemporaries at the upper echelons of the Indian Forest Service in the 1870s. It would be interesting to know how the policies evolved. The early Australian bushfire policies (largely derived from Indian colonial forestry) dictated fire exclusion and opposed prescribed burning, but were eventually overthrown in the 1950s and 1960s, having been undermined by two factors. First, they failed the ultimate test: they did not prevent damaging wildfires. Second, they were opposed from below by the people in the field – the forest officers who were responsible for implementing the policy and who knew it did not and could not work. Eventually, some of these men reached a position in which they could re-make the policy, and luckily they had the guts and the capacity to do so.

There is another factor. I remember a story once told to me by an old field forester who had worked in the jarrah forest in the late 1930s and early 1940s when the bushfire policy was still one of fire exclusion. “Beyond the narrow firebreak strips, we weren’t allowed to do any burning,” he said, “but what we did do, whenever possible, was to let the bush burn of its own accord.” In other words, if a fire started under the right conditions, there would be no hurry to put it out and, who knows, maybe some of these fires started quite accidentally from the escape of a forest officer’s billy fire, lit under exactly the right conditions.

The capacity to circumvent unpopular policy has been around as long as there have been unpopular policies. It is intriguing to think how M.J Slym managed it in British Burma in the 1870s, as I have no doubt he did.

Endnotes

[1] Underwood, Roger. 2010. Baden-Powell and Australian Bushfire Policy. Western Institute for Study of the Environment Forest and Fire Sciences Colloquium, January 2010 [here]

[2] Slym, M.J. 1877. Memorandum on Jungle Fires. The Indian Forester Volume 2 (3).

[3] It might be suggested that the differences between Burmese teak and Australian eucalypt forest are so different that no comparison over management can be made. It is true that teak is deciduous, but by the same token most eucalypts shed their entire leafy crown every 12-18 months. Furthermore, although mostly the teak forests are more humid, the dry sclerophyll eucalypt forests have a quite distinct wet and dry season, and in both the most suitable time to undertake low intensity burning is early in the dry season (late spring in southern Australia).

[4] Slym is referring here to a paper by a Colonel Pearson published in The Indian Forester in 1876, in which Pearson concluded: “In the Boree Forest of the Central Provinces, where fires have been put out for many years, it has been found that at least one hundred seedlings of Dalbergia and Pentaptera spring up for every one of teak.”

[5] My colleague, South Australian forester Jerry Leech, has worked in Burma on many occasions in recent years, and has described to me his delight in inspecting natural teak stands managed under a selection system, cut and regenerated four times over the last century, still magnificent today and the records of each cut still meticulously maintained.

[6] To give him credit, the Editor of the edition of The Indian Forester in which Slym’s paper was published was Baden-Powell. He added a footnote to the title of the paper as follows: “We trust the above memorandum will cause a vigorous discussion of the subject of fire protection.”

[7] My father, an agricultural scientist, fell foul of this law. In the 1920s he was a junior officer of the Department of Agriculture, and wrote a letter to The West Australian newspaper critical of the government for not insisting on the Pasteurisation of milk. My father got off lightly: he was hauled before the Director and officially reprimanded, but under the regulations he could have been fined or sacked. Ironically, a law was introduced not long afterwards making Pasteurisation of milk compulsory – a significant factor in reducing the prevalence of tuberculosis. My father took no credit for this, as the Pasteurisation of milk was universally adopted by western countries at about that time.

The 1910 Fires A Century Later: Could They Happen Again?

Jerry Williams. 2010. The 1910 Fires A Century Later: Could They Happen Again? Inland Empire Society of American Foresters Annual Meeting, Wallace, Idaho, 20-22 May 2010.

Note: Jerry Williams is retired U.S. Forest Service, formerly Director, USFS Fire & Aviation

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

“The future isn’t what it used to be.” — Variously ascribed

Background and Introduction

The United States has a history of large, catastrophic wildfires. 1910’s Big Burn, a complex covering some 3,000,000 acres across Washington, Idaho, and Montana was certainly among the largest. It was also among the deadliest. As Stephen Pyne and Timothy Egan have described, it stunned the nation, changed the day’s political dynamic, and galvanized support for the protection of public lands. The Big Burn spawned an enormous effort to control this country’s wildfire problem.

One-hundred years later, solving the wildfire problem in this country remains elusive.

Since 1998, at least nine states have suffered their worst wildfires on record. Perhaps like the Big Burn, these recent wildfires were remarkable, but, unlike 1910, not for want of firefighting capacity. In the modern era, these unprecedented wildfires are juxtaposed against the fact that today’s firefighting budgets have never been higher, cooperation between federal, state, and local forces have never been better, and firefighting technology has never been greater. How could fires like this - with all of today’s money and partnerships, and tools – how could they happen? How could modern wildfires approach the scale and scope of wildfires from a hundred years ago?

In 2003, following a decade of record-setting wildfires across the country, the U.S. Forest Service began looking into what would become known as the mega-fire phenomenon. A comparative, coarse-scale assessment of nine “mega-fires” was completed in 2008 1/.

1/ The report’s findings were presented at the Society of American Forester’s National Convention in Orlando, Florida on 2 October 2009 in a paper titled, “The Mega-Fire Phenomenon: Observations from a Coarse-Scale Assessment with Implications for Foresters, Land Managers, and Policy-Makers,” by Jerry T. Williams and Dr. Albert C. Hyde. The views expressed in these reports and papers are those of the author(s). They do not purport to represent the positions of The Brookings Institution or the U.S. Forest Service.

Will another 1910-like wildfire happen again? No matter how low the probability, recent mega-fires are testament that large, catastrophic wildfires can happen in today’s world. Who would believe that, in 2003, 15 people would lose their lives and over 3,000 homes would burn outside of San Diego; in a State that arguably fields the largest firefighting force in the world? Who would think that, within sight of the Acropolis in 2007, 84 people would die from a wildfire running into Athens, Greece? And, who could fathom that, a year ago last February, whole towns would be consumed and 173 people would die from bushfires in Victoria that would become the largest civil disaster in Australia’s history?

The increasing frequency of mega-fires makes it un-wise to dismiss them as anomalies and somehow accept them as too rare to address or too difficult to mitigate. Global warming, the vulnerability of deteriorated fire-dependent landscapes, and growth behaviors at the wildland-urban interface have changed the calculus of wildland fire protection in the United States and elsewhere around the world. The trajectories that these factors are taking suggest that mega-fire numbers will grow, not diminish. If we are asking the “chance” of catastrophe, these factors have changed the odds of wildfire disaster.

Mega-fires are important indicators that reflect an unwelcome “new reality.” Their impacts go far beyond today’s immediate concerns over rising suppression costs. They carry significant implications for foresters, land managers, and policy-makers.

Will another 1910-like wildfire occur? Modern mega-fires offer insights that might help us answer and respond to this question. If you trust the fireman’s adage that, “when wildfire’s potential consequences are high, going-home gas is cheap,” it is in our best interests to take notice, proactively study these catastrophic wildfires, and act on their lessons.

Climate Changes and their Effects on Northwest Forests

Schlichte, Ken. 2010. Climate Changes and their Effects on Northwest Forests. Northwest Woodlands, Spring 2010.

Ken Schlichte is a retired Washington State Department of Natural Resources forest soil scientist. Northwest Woodlands Magazine [here] is a quarterly publication produced in cooperation with woodland owner groups in Oregon, Washington, Idaho and Montana.

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

Climate changes are always occurring, for a variety of reasons. Climate changes were responsible for the melting and retreat of the Vashon Glacier back north into Canada at the beginning of the postglacial Holocene Epoch around 11,000 years ago. Climate changes were also responsible for the warmer temperatures of the Holocene Maximum from around 10,000 to 5,000 years ago, the warmer temperatures of the Medieval Warm Period around 1,000 years ago and the coldest temperatures of the Little Ice Age during the Maunder Minimum around 300 years ago. These climate changes, the reasons for them and their effects on our Northwest forests are discussed below.

Forests soon became established on the glacial soil deposits left by the retreat of the Vashon Glacier, but some of these forests were later replaced by prairies and oak savannahs as temperatures increased during the Holocene Maximum. …

Forests began advancing into the South Puget Sound area prairies and replacing them as temperatures began decreasing following the Holocene Maximum. Native Americans began burning these prairies in order to maintain them against the advancing forests for their camas-gathering and game-hunting activities. Forest replacement of these and other Northwest prairies has proceeded rapidly since the late-1800s in the absence of these burning activities. …

The warmer temperatures and increased solar activity of the Medieval Warm Period were followed by a period of cooler temperatures and reduced solar activity known as the Little Ice Age. The coldest temperatures and lowest solar activity of the Little Ice Age both occurred during the Maunder Minimum from 1645 to 1715… The Dalton Minimum was a period of lower solar activity and colder temperatures from 1790 to 1820. Mount Rainier’s Nisqually Glacier reached a maximum extent in the last 10,000 years during the colder temperatures of the Maunder Minimum and the Dalton Minimum and then began retreating as Northwest temperatures warmed following the mid-1820s and the Dalton Minimum. Beginning in 1950 and continuing through the early 1980s the Nisqually Glacier and other major Mount Rainer glaciers advanced in response to the relatively cooler temperatures and higher snowfalls of the mid-century, according to the National Park Service. …

Fuel treatments, fire suppression - Warm Lake

Graham, Russell T.; Jain, Theresa B.; Loseke, Mark. 2009. Fuel treatments, fire suppression, and their interaction with wildfire and its impacts: the Warm Lake experience during the Cascade Complex of wildfires in central Idaho, 2007. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-229. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 36 p.

Full text [here] (9.3MB)

Selected excerpts:

Abstract

Wildfires during the summer of 2007 burned over 500,000 acres within central Idaho. These fires burned around and through over 8,000 acres of fuel treatments designed to offer protection from wildfire to over 70 summer homes and other buildings located near Warm Lake. This area east of Cascade, Idaho, exemplifies the difficulty of designing and implementing fuel treatments in the many remote wildland urban interface settings that occur throughout the western United States. The Cascade Complex of wildfires burned for weeks, resisted control, were driven by strong dry winds, burned tinder dry forests, and only burned two rustic structures. This outcome was largely due to the existence of the fuel treatments and how they interacted with suppression activities. In addition to modifying wildfire intensity, the burn severity to vegetation and soils within the areas where the fuels were treated was generally less compared to neighboring areas where the fuels were not treated. This paper examines how the Monumental and North Fork Fires behaved and interacted with fuel treatments, suppression activities, topographical conditions, and the short- and long-term weather conditions.

Introduction

The Payette Crest and Salmon River Mountain ranges of central Idaho create rugged and diverse landscapes. The highest elevations often exceed 10,000 ft with large portions ranging from 5,500 to 6,500 ft above sea level. The Salmon River and its tributaries dissect these mountains creating an abundance of steep side slopes. The South Fork of the Salmon River, with its origin within the 6,000- to 7,000-ft mountains east of Cascade, Idaho, flows north until it joins the main Salmon at an elevation of 2,100 ft. At 5,300 ft, the Warm Lake Basin near the South Fork’s origin is one of the many large and relatively flat basins that occur in central Idaho (Alt and Hyndman 1989; Steele and others 1981) (fig. 1). …

Forest Treatments in the Wildland Urban Interface Near Warm Lake

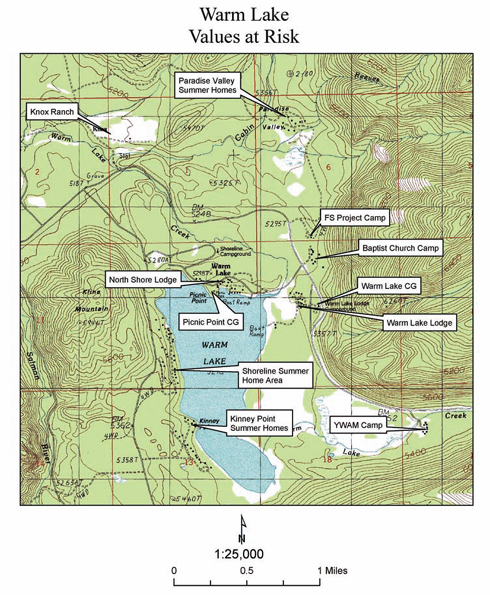

A large proportion (>66%) of Idaho lands are owned and/or administered by state and federal governments (NRCM 2008). In addition, there are over 30,000 residences located on lands in the wildland urban interface (WUI) with many of these residences being on lands leased from state or federal governments. Valley County, located in the central part of the Idaho, has over 2,200 residences located in the WUI with a concentration of structures near Warm Lake (Headwaters Economics 2007) (fig. 1). Within the Warm Lake area, approximately 20 miles northeast of Cascade, there are roughly 70 residences and other structures (fig. 3). In addition to the summer homes, the area contains two commercial lodges, two organizational camps, and a Forest Service Project Camp. The Warm Lake Basin is the headwater for the Salmon River, which is home to both Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchu tshawytscha) and steelhead trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Both species are listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act, which highlights the Salmon River’s ecological and commercial value. Because of these threatened species, the amount of vegetative manipulation occurring within the Salmon River drainage since the mid-1970s has been minimal (USDA Forest Service 2003).

Figure 3. Several homes, lodges, camp grounds (CG), Forest Service camps (FS), and other developments are located within the Warm Lake area of central Idaho. Click map for larger image.

The Fictional Ecosystem and the Pseudo-science of Ecosystem Management

Travis Cork III. 2010. The Fictional Ecosystem and the Pseudo-science of Ecosystem Management. W.I.S.E. White Paper No. 2010-3, Western Institute for Study of the Environment.

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

LAND USE CONTROL has long been the goal of the statist element in our society. Zoning was the first major attempt at land use control. Wetland regulation and the Endangered Species Act have extended some control, but nothing has yet brought about a general policy of land use control. Ecosystem management is an attempt to achieve that end.

The fictional ecosystem

In The Use and Abuse of Vegetational Concepts and Terms, A. G. Tansley coined the term “ecosystem.” Tansley rejected the “conception of the biotic community” and application of the “terms ‘organism’ or ‘complex organism’” to vegetation. “Though the organism may claim our primary interest, when we are trying to think fundamentally we cannot separate them from their special environment, with which they form one physical system. It is the systems so formed which, from the point of view of the ecologist, are the basic units of nature on the face of the earth. … These ecosystems, as we may call them, are of the most various kinds and sizes… which range from the universe as a whole down to the atom” 1/

Tansley further writes “[e]cosystems are extremely vulnerable, both on account of their own unstable components and because they are very liable to invasion by the components of other systems. … This relative instability of the ecosystem, due to the imperfections of its equilibrium, is of all degrees of magnitude. … Many systems (represented by vegetative climaxes) which appear to be stable during the period for which they have been under accurate observation may in reality have been slowly changing all the time, because the changes effected have been too slight to be noticed by observers.” 2/

Lackey confirms writing “[t]here is no ‘natural’ state in nature; it is a relative concept. The only thing natural is change, some-times somewhat predictable, oftentimes random, or at least unpredictable. It would be nice if it were otherwise, but it is not.” 3/

The ecosystem may be the basic unit of nature to the ecologist, that is—man, but it is not the basic unit to nature. Its proponents confirm that it is a man-made construct.

We are told in Creating a Forestry for the 21st Century: The Science of Ecosystem Management that “ecosystems, in contrast to forest stands, typically have been more conceptual than real physical entities.” 4/

The Report of the Ecological Society of America Committee on the Scientific Basis for Ecosystem Management tells us “[n]ature has not provided us with a natural system of ecosystem classification or rigid guidelines for boundary demarcation. Ecological systems vary continuously along complex gradients in space and are constantly changing through time.” 5/

“People designate ecosystem boundaries to address specific problems, and therefore an ecosystem can be as small as the surface of a leaf or as large as the entire planet and beyond.” 6/

“Defining ecosystem boundaries in a dynamic world is at best an inexact art,” says the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) in its 1995 publication, Integrating Social Science and Ecosystem Management: A National Challenge.

“Among ecologists willing to draw any lines between ecosystems, no two are likely to draw the same ones. Even if two agree, they would recognize the artificiality of their effort…” 7/ …

Defining, Identifying, and Protecting Old-Growth Trees

Mike Dubrasich. 2010. Defining, Identifying, and Protecting Old-Growth Trees. W.I.S.E. White Paper 2010-1. Western Institute for Study of the Environment.

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts [here]

IN ORDER TO SOLVE our current forest crisis and protect our old-growth, it is useful to understand what old-growth trees are and how to identify them in the field.

At first blush this may seem to be a simple problem, but it is not, and much confusion and debate abounds over the issue. Old-growth trees are “old,” but how old does a tree have to be to qualify as “old-growth”? And what is the difference between an individual old-growth tree and an old-growth stand of trees? Why does it matter?

Some rather sophisticated understanding of forest development is required to get at the root of these questions. …

Reduced Fire Frequency Changes Species Composition of a Ponderosa Pine Stand

Alan Dickman. 1978. Reduced Fire Frequency Changes Species Composition of a Ponderosa Pine Stand. Journal of Forestry, January 1978.

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

Abstract

In the Umpqua National Forest, Oregon, a 35-acre ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa Laws.) stand situated in the midst of a Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii [Mirb.]Franco) forests is being invaded by Douglas-fir seedlings as a result of reduced fire frequency within the last 50 years. In earlier times frequent ground fires kept Douglas-fir at a minimum.

Pine Bench, an area on the Umpqua National Forest, Oregon, is undergoing a drastic change in species composition. The understory, which according to an early settler, Jessie Wright (personal communication, 1975), was open and grassy until a half-century ago, now contains thickets of Douglas-fir that are shading out seedlings of the overstory ponderosa pines. A study was made to determine the cause and extent of this shift. …

Results

The size-class distribution (fig .1) shows that among the large trees there are far more ponderosa pines than Douglas-firs, while among the small trees there are far more Douglas-firs than ponderosa pines. The age class distribution (fig. 2) shows that the change occurred rather suddenly. …

The linear regressions show that Douglas-fir grows faster than ponderosa pine on Pine Bench; Douglas-fir appearing in the same size-class is actually younger. Therefore, the difference in the large number of old ponderosa pine and the small number of old Douglas-fir is actually even greater than the size-class distribution indicates.

The shift in, species composition began, then, when the middle-aged trees were seedlings. The number of Douglas-fir germinating and surviving was relatively small and stable until 1925, but thereafter increased steadily up to the present.

Discussion

The change seems too quick and drastic to be a result of natural succession. Grazing does not seem responsible, either. According to Jessie Wright (personal communication) cattle were driven through Pine Bench from 1917 to 1952 on their way between summer and winter grazing areas. The cattle were never on the bench long, however, and their impact was slight. Furthermore, Mrs. Wright told me that they grazed fir in preference to pine.

Reduced fire frequency seems the most likely cause of the invasion. …

Two factors may have combined to reduce the frequency of fires on Pine Bench in this century. First is the absence of Indian or settler-caused fires, although as early as 1840 the number of Indians in the North Umpqua Valley was very small (Bakken 1970). An equally likely cause is the suppression of fires by the U.S. Forest Service.

By 1920, a Forest Service fire lookout was established on Illahee Rock, only four miles from Pine Bench, although it was not until the introduction of aerial fire-fighting techniques that control became highly effective. Douglas-firs living through the 1920s and 1930s would have almost been assured of survival once the more effective fire suppression of later decades began.

Prescribed burning has been proven valuable and workable in maintaining ponderosa pine stands (Weaver 1964, 1965) and should be considered for Pine Bench.

Spark and Sprawl: A World Tour

Stephen J. Pyne. 2008. Spark and Sprawl: A World Tour. Forest History Today, Fall 2008.

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

Wildland-urban interface” is a dumb term for a dumb problem, and both have dominated the American fire scene for nearly twenty years. It’s a dumb term because “interface” is a pretty klutzy metaphor and because the phenomenon of competing borders it describes is more complex than that geeky term suggests. At issue is a scrambling of landscape genres beyond the traditional variants of the American pastoral. It is a mingling of the quasi-urban and the quasi-wild into something that, depending on your taste, resembles either an ecological omelet or a coniferous strip mall. That means it also stirs together urban fire services with wildland fire agencies, two cultures with no more in common than an opera house and a grove of old-growth ponderosa pine. It is an unstable alloy, a volatile compound of matter and antimatter, and it should surprise no one that it explodes with increasing regularity.

It’s a dumb problem because technical solutions exist. We know how to keep houses from burning on the scale witnessed over the past two decades. We know convincingly that combustible roofing is lethal; we have known this for maybe ten thousand years. The wildland-urban interface (WUI) fire problem (a.k.a., the interface or I-zone) thus differs from fire management in wilderness, for example, where fire practices must be grounded, if paradoxically, in cultural definitions and social choices; there is no code to ensure that the right fire happens in the right way.

That the intermix problem persists testifies to its relatively trivial standing in the larger political universe, even as construction pushes ever outward into the environmental equivalent of subprime landscapes, which from time to time then crash catastrophically. In that regard it remains on the fringe. …