Genetic variation in the southern pines: evolution, migration, and adaptation following the Pleistocene

Ronald Schmidtling. 2007. Genetic variation in the southern pines: evolution, migration, and adaptation following the Pleistocene. IN Kabrick, John M.; Dey, Daniel C.; Gwaze, David, eds. Shortleaf pine restoration and ecology in the Ozarks: proceedings of a symposium; 2006 November 7-9; Springfield, MO. Gen. Tech. Rep. NRS-P-15. Newtown Square, PA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station: 28-32.

Full text [here]

Selected excerpts:

ABSTRACT

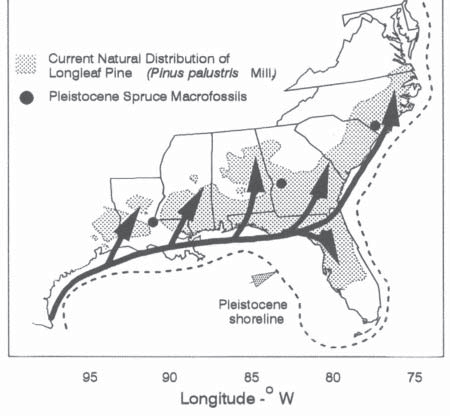

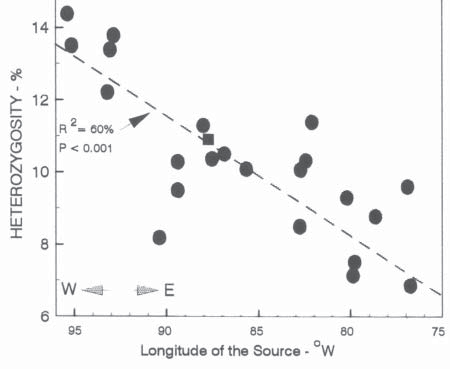

Climate has certainly changed over time, requiring genetic change or migration of forest tree species. Little is known about the location of the southern pines during the Pleistocene glaciation, which ended around 14,000 years ago. Macrofossils of spruce (Picea spp.) dating from the late Pleistocene, which are typical of climates much cooler than presently occupied by the southern pines, have been found within the current range of the southern pines, indicating that the climate was considerably colder at that time. From this discovery it is reasonable to assume that the southern pines were situated south of their present range during the Pleistocene and migrated to their current location after the glaciers receded. Variation in adaptive and non-adaptive traits of the southern pines suggests that loblolly pine (Pinus taeda) existed in two refugia, one in south Texas/north Mexico, and one in south Florida. Longleaf pine (P. palustris) probably existed only in the western refugium. Slash pine (P. elliottii), on the other hand, presumably resided only in the Florida refugium, whereas shortleaf pine (P. echinata) is cold-hardy enough to have existed in a continuous distribution across the Gulf Coast. Implications of climate warming on the future of southern pines are discussed.

CONCLUSIONS

In spite of the relative uniformity of the Coastal Plain of the southeastern United States, important genetic differences exist among the southern pine species in response to the last glaciation. Longleaf pine resided in a southwestern refugium and slash pine in a Florida refugium. Loblolly pine resided in both refugia, the two populations being isolated genetically. Shortleaf pine probably resided in a continuous population across the exposed continental shelf. The many advances and retreats of glaciation during the Pleistocene undoubtedly had profound effects on variation and speciation in the southern pines.

Figure 2.—Post-Pleistocene migration route accounting for the variation. Adapted from Schmidtling and Hipkins (1998).

Figure 3.—Variation in expected heterozygosity by longitude in longleaf pine. Adapted from Schmidtling and Hipkins (1998).

Figure 4.—Current natural distribution of loblolly pine showing the frequency of trees with high cortical limonene content. Also shown are the proposed Pleistocene refugia and migration routes.

Figure 5.—Proposed location of the major southern pines during the Wisconsin Glaciation.

After the Ice Age

Pielou, E.C., After the Ice Age: The Return of Life to Glaciated North America. 1991, Univ. Chicago Press.

Review by Mike Dubrasich

The smartest woman in the world is a little old lady who lives on Vancouver Island in British Columbia. Eighty-ish and now retired, Evelyn putters about her garden, does her shopping, and lives her life in relative obscurity. Her neighbors must know and love her, and they must find her to be very bright, but they may not realize just how smart she is.

Evelyn has described herself as a “naturalist,” but she is better known to the scientific world as Dr. E. C. Pielou, the inventor of mathematical ecology.

Mathematical ecology involves the quantification and statistical analysis of natural phenomena. Dr. Pielou’s book, Introduction to Mathematical Ecology (1969), is the bible of the field. It is not a light read. To get the most out of it requires a background in ecology and statistics at the post-graduate level. However, if you wish to measure something in the environment and do not follow Evelyn’s advice on the matter, you are doing it wrong.

Dr. Pielou holds Ph.D. and D.Sc. degrees from the University of London. She has been a professor at the Yale School of Forestry, Dalhousie University, Halifax, and the University of Lethbridge, Alberta, as well as holding a variety of guest lectureship positions all over. In 1984 she was awarded the Lawson Medal of the Canadian Botanical Association and in 1986 she won the Eminent Ecologist Award of the Ecological Society of America. The ESA has also established the E.C. Pielou Award, a competitive award made annually to a graduate student or recent Ph.D. graduate based on overall quality of the student’s scientific contribution to statistical ecology.

Dr. Pielou has written some popular science books, as well as dozens of technical scientific papers. Her books include:

Ecological Diversity (1975)

The Interpretation of Ecological Data: A Primer on Classification and Ordination (1984)

The World of Northern Evergreens (1988)

Biogeography (1992)

A Naturalist’s Guide to the Arctic (1995)

Fresh Water (1998)

The Energy of Nature (2005)

Her most famous (fame is subjective) “pop” book, and one that perhaps has more significance today than when she wrote it, is After the Ice Age: The Return of Life to Glaciated North America (1991).

In After the Ice Age Dr. Pielou describes the ecological changes that have occurred in North America over the last 20,000 years.

We live in a glacial age, something rare in the history of the Earth. Our current glacial age (the Pleistocene) began two million years ago (roughly). The most recent previous glacial age was during the Permian Epoch, 250 million years ago.