Two-Thirds of Idaho Wolf Carcasses Examined Have Thousands of Hydatid Disease Tapeworms

By George Dovel, The Outdoorsman, No. 36, Dec. 2009 [full text here]

NOTE: see also [here]

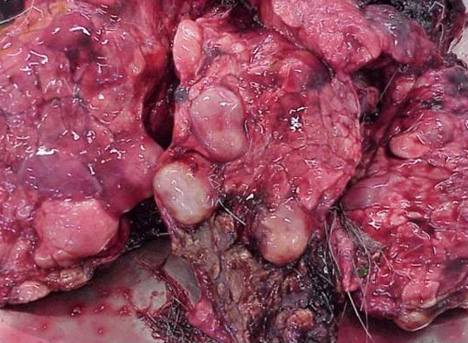

Hydatid cysts infect lungs, liver, and other internal organs of big game animals. Michigan DNR Wildlife Disease Lab photo

Hydatid cysts infecting moose or caribou lungs. Photo courtesy of NW Territories Department of Environment and Natural Resources.

My first Outdoorsman article on hydatid disease caused by the tiny Echinococcosis granulosus tapeworm was published nearly 40 years ago. Back then we had many readers in Alaska and northern Canada where the cysts were present in moose and caribou and my article included statistics on the number of reported human deaths from these cysts over a 50-year period, and the decline in deaths once outdoorsmen learned what precautions were necessary to prevent humans from being infected.

In Alaska alone, over 300 cases of hydatid disease in humans had been reported since 1950 as a result of canids (dog family), primarily wolves, contaminating the landscape with billions of E. granulosus eggs in their feces (called “scat” by biologists). These invisible eggs are ingested by grazing animals, both wild and domestic, and occasionally by humans who release clouds of the eggs into the air by kicking the scat or picking it up to see what the wolf had been eating.

As with many other parasites, the eggs are very hardy and reportedly exist in extremes of weather for long periods, virtually blanketing patches of habitat where some are swallowed or inhaled. As Dr. Valerius Geist explained in his Feb-Mar 2006 Outdoorsman article entitled Information for Outdoorsmen in Areas Where Wolves Have Become Common, “(once they are ingested by animals or humans) the larvae move into major capillary beds – liver, lung, brain – where they develop into large cysts full of tiny tapeworm heads.”

He continued, “These cysts can kill infected persons unless they are diagnosed and removed surgically. It consequently behooves us (a) to insure that this disease does not become widespread, and (b) that hunters and other outdoorsmen know that wolf scats and coyote scats should never be touched or kicked.”

[NOTE: moisture around waterholes reportedly preserves the eggs in high temperatures that might otherwise destroy them. Ingestion of E. granulosus eggs by drinking the water is also possible. - ED]

Dr. Geist’s article also warned, “If we generate dense wolf populations it is inevitable that such lethal diseases as Hydatid disease become established.” Because wolves and other canines perpetuate the disease by eating the organs of animals containing the cysts, and the tapeworms live and lay millions of eggs in their lower intestines, the logical way to insure the disease did not develop was not to import Canadian wolves that were already infected with the parasites.

Despite Warnings From Experts. FWS and IDFG Ignored Diseases, Parasites Spread by Wolves

This was common knowledge among wildlife biologists in northern Canada and in Alaska where FWS biologist Ed Bangs was stationed prior to being assigned to head the Northern Rocky Mountain Wolf Recovery Team. Yet in the July 1993 Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) provided to the public, Bangs chose not to evaluate the impact of wolf recovery on diseases and parasites (1993 DEIS page 1-17).

This alarmed a number of experts on pathogens and parasites, including Will Graves who began his career working to eradicate foot and mouth disease in Mexico. As an interpreter who conducted research of Russian wolf impacts on wildlife, livestock and humans for several decades, Graves provided Bangs with information that wolves in Russia carry 50 types of worms and parasites, including Echinococcosis and others with various degrees of danger to both animals and humans.

In his Oct. 3, 1993 written testimony to Bangs, Graves also cited the results of a 10-year Russian control study in which failure to kill almost all of the wolves by each spring resulted in up to 100% parasite infection rate of moose and wild boar with an infection incidence of up to 30-40 per animal. This compared to a 31% infection rate with an incidence of only 3-5 per animal where wolves were nearly eliminated each winter.

Graves’ letter emphasized that despite the existence of foxes, raccoons and domestic dogs, wolves were always the basic source of parasite infections in moose and boar. He also emphasized the toll this would take on livestock producers and, along with other expert respondents, requested a detailed study on the potential impact wolves would have in regard to carrying, harboring and spreading disease.

In the final 414-page Gray Wolf EIS (FEIS) dated April 14, 1994, only a third of a page addresses “Diseases and Parasites to and from Wolves” (Chapter 5 Page 55). It states: “Most respondents who commented on this issue expressed concern about diseases and parasites introduced wolves could transfer to other animals in recovery areas.”

Bangs’ response states, “Wolves will be given vaccinations when they are handled to reduce the chances of them catching diseases from coyotes and other canids. Then Bangs stated, “Wolves will not significantly increase the transmission of rabies and other diseases,” yet offered nothing to substantiate his false claim. …

IDFG Officially Discovered Hydatid Disease in 2005-06

In mid 2005, state wildlife health officials in Idaho began conducting necropcies (post mortem examinations) of many wildlife species. As in Minnesota, Michigan and Wisconsin, they found a number of the primary big game species they tested were infected with hydatid cysts – but only the Great Lakes wildlife agencies reported that fact to the public.

It is reasonable to assume that Michigan DNR’s publication of warnings to use protective gear when handling wolf scat and wolf carcasses and not let your dog eat internal organs from deer, moose, etc. may have saved a significant number of hunters and/or their children from becoming infected with hydatid disease.

It is also reasonable to assume that Idaho Fish and Game’s failure to publish similar warnings during the four hunting seasons that have come and gone since the disease was officially discovered in Idaho may have allowed a significant number of Idaho hunters and/or their children to become infected with hydatid disease. [emphasis added]

[In November and December, 2009, and in January 2010] at Idaho Hunting Today and other Black Bear Blog websites, Tom Remington first revealed the results of the Washington laboratory checking Idaho and Montana wolf intestines for E. granulosus tapeworms. See [here, here, here] …

ID, MT F&G Ignored Responsibility to Warn Public

Instead of fulfilling their responsibility to see that hunters and ranchers in Idaho and Montana received instruction on how to protect themselves from becoming infected, from 2006-2008 Drew and two of his counterparts from Montana participated in the evaluation of the lower intestines of 123 more wolves from Idaho and Montana. This is the study reported by Tom Remington on Dec. 13, 2009, in which 62% of Idaho wolves and 63% of Montana wolves contained E. granulosis tapeworms, and 71% of all the wolves tested contained Taenia sp, also predicted by Will Graves.

The study report says: “The detection of thousands of tapeworms per wolf was a common finding,” and also said: “Based on our results, the parasite is now well established in wolves in these states and is documented in elk, mule deer, and a mountain goat as intermediate hosts.” Of the wolves that contained E. granulosis, more than half contained more than 1,000 worms per wolf. …

The study reported that the prevalence of E. granulosis tapeworms in wolves in Canada, Alaska and Minnesota varied from 14% to 72% and said the 63% rate found in Idaho and Montana was comparable. …

During the past 20 years, medical case histories suggest that the course of the northern (sylvatic) strain of Hydatid Disease where wolves infect wild cervids (deer, elk, moose, etc.) is normally less severe on most humans than the domestic (pastoral) strain where dogs infect domestic sheep and other ruminants. The authors of the wolf parasite study used this information to try to downplay the potential impact of hydatid disease transmitted by wolves to humans in Idaho and Montana.

They also included the following statement to create the false impression that there is limited chance of Idaho and Montana residents becoming infected: “Most human cases of hydatid disease have been detected in indigenous peoples who hunt wild cervids or are reindeer herders with dogs.” At least part of that statement is accurate because most of the people who live in isolated areas and are more exposed are either Indians or Eskimos.

But they neglect to mention that several hundred thousand people in Idaho and Montana also hunt wild cervids and thousands more work or recreate where wolves have contaminated the land and drinking water with the parasite eggs. Unless the cysts are formed in the brain, heart, spleen or kidneys, infected people may carry them undetected for years, while they slowly grow larger until they eventually create severe problems or death.

Because the death of most people from so-called natural causes is attributed to heart failure, etc., without an autopsy being performed, the actual number of deaths resulting from hydatid disease remains a matter of speculation. Case histories reveal that detection of hydatid disease in living humans often occurs as a result of a CT Scan or Ultrasound performed for another reason.

Dr. Geist’s reply to the lack of concern expressed for humans who will become infected was, “It’s nothing to fool around with. Getting an Echinococcus cyst of any kind is no laughing matter as it can grow not only on the liver or the lungs, but also in the brain. And then it’s fatal.”

He also asked if another parasite, E. multilocularis, found in Alberta wolves, also exists in the transplanted wolves in Idaho and Montana. “(It‘s) much more virulent than Echinococcus granulosus of any strain, we cannot encapsulate this cyst, and it grows and buds off like a cancer infecting different parts of the body incessantly.”

[NOTE: Three separate studies conducted over a 10-year period in Minnesota concluded that 87% of moose mortality is related to parasites and infectious diseases. The insanity of pretending to restore “healthy” ecosystems by allowing uncontrolled large carnivores to spread parasites and diseases is becoming painfully obvious – ED]

by YPmule

by Gary T.

A couple years ago I gutted an elk on the Idaho/Montana border. The lungs had grape size purple balls all through them. I thought it was T.B., but after seeing these pictures I’m not so sure it wasn’t this. I didn’t have gloves and got covered with blood like you always do with elk. Because I was worried about whatever was wrong with it, I washed my hands as soon as I got back to camp (1-2hours later). How much do I need to worry about this? I have no health insurance. How do they test for this and is it treatable? What about cost? The purple balls on the lungs were hollow and filled with liquid. I asked Idaho Fish and Game about it and they agreed it was probably T.B and said I probably had nothing to worry about. It was not my elk and I didn’t eat any of it. If it had been mine would I need to worry about eating it? Thanks

Gary, Please read the Echinococcosis Fact Sheet [here]. It states:

There are no precautions that need to be taken when handling tissue of the intermediate hosts as the lung cysts are not infective to humans.

However, that does not mean that you are not infected. Please do not trust websites for your medical care. The Fact Sheet also says:

Diagnosis of E. granulosus in humans is accomplished through an ELISA test which uses an antigen preparation (hydatid fluid) which detects antibodies. Serological testing can also be performed to determine the presence of oncosphere, cyst fluid, and/or protoscolex antibodies in the serum. The presence of hydatid cysts can be determined on autopsy examination.

I interpret that to mean that a blood test is the definitive diagnostic method, short of autopsy. Ask your doctor if he can perform such a test, and if it’s worth it to you, get one done. It is possible to obtain such a test without health insurance. You just have to pay for it yourself. If it’s worth it to you.

I am not a doctor, nor do I play one on TV. Please consult a professional licensed physician.

I live in East Glacier Park Montana. I have 2 female (spayed) Alaskan Malamutes. This is hunting season and my dogs keep bringing home deer hides and animal parts, bones, deer hides, and etc. Now I have noticed my dogs are very sick. At first I thought maybe mange because I am unfamiliar with wildlife parasites. Now I am suspecting worms and such after reading your article. I first noticed whining or whimpers, then itching and scratching. Their scratching is more like biting the skin and loss of hair, yet it doesn’t seem like mange. My dogs are well kept and generally healthy. I noticed too that they quiver in the intestines badly and their breathing doesn’t seem right.

Can you tell me more on symptoms or what to watch for to detect wild life parasites of this nature that is described in your article?

I do have an appointment with the Veterinarian this week. Perhaps I should ask them if possible to blood test my dogs. Also I do have de-wormer, WormXPlus by Sentryhc (pyrantel pamoate/praziquantel).

Reply: Describe all the above to your vet. Request (in no uncertain terms) blood testing for parasites including (but not limited to) hydatid tapeworms. If necessary, get a second opinion from a second vet. If your dogs test positive, you may want to get yourself tested, too.

Thanks for posting Mr. Dovel’s work here - this is an important topic and you don’t see this covered in FWS reports or the media.

This next bit is off topic, but I have not seen it mentioned anywhere I’ve read that predators can carry plague. Perhaps Mike will pop in one of his wonderful links that can enlighten us. I don’t think I’ve ever heard of “naturally occurring plague” in the Yellowstone area until today…

———————

Well-known Wyoming cougar dies of plague

The Associated Press 01/13/10

JACKSON, Wyo. — Biologists with the Grand Teton National Park say a female cougar who was known for wandering around the Jackson region has died of plague.

The 6-year-old cat, dubbed F13, was tagged with a global positioning system collar. Senior wildlife biologist Steve Cain says the carcass was found at the southern end of Grand Teton National Park, near the base of the Tetons.

At least five cougars in the Greater Yellowstone Area have died of plague in recent years. In 2008, a Boy Scout visiting Jackson contracted the disease and later recovered.

Plague, which is often carried by fleas, is naturally occurring in the region and researches say it doesn’t pose a threat to the overall cougar population.