Lasting Bitterness Over the Poe Cabin Fire

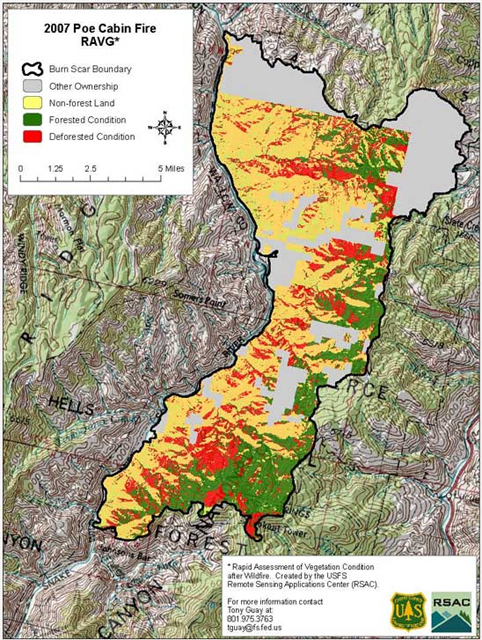

In 2007 the Poe Cabin Fire burned 59,686 acres in Western Idaho, mostly on the Nez Perce National Forest. Both forest and grazing land burned, including grazing allotments.

Map courtesy USFS Rapid Assessment of Vegetation Condition after Wildfire (RAVG) [here].

The Capital Press reported on the immediate aftermath in August of 2007:

Poe Cabin: The postmortem begins

Rancher questions Poe Cabin fire management

Patricia R. McCoy, Capital Press, 8/31/2007 [here]

LUCILE, Idaho - Heartbreak is too weak to describe it.

There’s nothing to see for miles but blackened trees, shrubs, and acres of ashes.

Someone brave enough to walk or ride back into the wrecked landscape away from the road can find dead or dying cattle and wildlife - their hooves and feet so badly burned there’s no hope of healing. The most merciful thing to do is shoot them.

Rancher Melvin Gill, his daughter Shelley and her husband, Garrett Neal, put eight calves out of their misery by Aug. 20. They know they must look for more, but it’s dangerous. They must constantly be watching over their heads as well as under their feet. Burned, dying tree trunks and branches can snap off at any moment, crashing down on whoever is underneath.

The old-time loggers called such falling snags widow makers, with good reason.

Plenty of animals are already dead, Gill and Neal said. They’re easy to find on the Cow Creek Allotment leased by the Gill family. Crows and other carrion eaters are readily spotted. They’re feasting in the wake of the Poe Cabin fire in the Seven Devils Mountains, on lands managed mainly by the U.S. Forest Service as the Wallowa-Whitman and Nez Perce National Forest, and the Hells Canyon National Recreation Area.

Loss goes beyond individual animals or numbers. There’s the ranch breeding program, bloodlines built up and improved over the years, and the future calves those heifers will never produce, the rancher said.

It’s the third time in 11 years Gill has been burned out. This time he seriously wonders if his operation can recover. The Neal’s love the lifestyle and hope to one day run the ranch themselves. They’re uncertain of their future. …

Now, almost two years later, the Capital Press offers the following guest editorial from Shelley Neal. Her story is one of lasting loss, broken promises, and a bitterness that will not go away.

Some wounds from Poe Cabin Fire may never heal

by Shelley Neal, Guest Comment, Capital Press, July 9, 2009 [here]

In July 2007, the Poe Cabin Fire burned through our Forest Service grazing allotment in Western Idaho, an allotment my family has held a permit on for over 100 years.

This Cow Creek allotment is located between the Snake and Salmon rivers above Lucile, Idaho. Our allotment has been and still is technically managed by the Nez Perce National Forest, although in 1975 the creation of the Hells Canyon National Recreation Area, managed by the Wallowa-Whitman National Forest, brought about a long struggle of inconsistent management that began to plague this allotment as well as adjoining allotments.

Forest Service mismanagement has gotten out of hand.

The Poe Cabin Fire burned more than 50,000 acres covering 17 miles along the Snake River and cost more than $15 million! Mother Nature went to work after the smoke cleared, but even two years later, scars of this fire still loom visibly over the landscape. Majestic pine trees, once so tall and green, are now only burnt chunks wasting away on the ground, no longer homes to squirrels, birds or bugs.

Under the boughs of these grand trees one used to be able to hunker down and weather out a bad storm. Now you’d be afraid to even lean against these black sticks. The scorched ground cannot even produce weeds in many areas, and in other areas noxious weeds are the only thing growing in the burned soil.

Walking through the remains of the Poe Cabin Fire still gives me an eerie feeling. Gone are all the familiar sights, sounds and smells I’ve ridden through for over 40 years.

The Poe Cabin Fire destroyed several historical and cultural homestead sites. Ironic, since the Hells Canyon National Recreation Area Act established on Dec. 31, 1975, was to protect such values.

The Forest Service even discovered two additional historical and cultural sites after this fire. One was an old hand-dug ditch line, quite visible to the common eye, over which the Forest Service installed a vault toilet in the late 1980s. Did the service not follow its own rules and regulations by first doing an archeology study before digging? Apparently not.

Its other discovery was a sheepherder’s carving of a “happy face” from the ’30s on a large pine tree. This historical landmark sat beside a main trail, obviously not one the Forest Service maintained, or they would have been aware of this site.

One doesn’t learn the land by looking on a map or traveling through the area a couple of times. One learns the land by living on it and knowing the history of the folks who helped to shape it.

Now, the permit holders are left to live with the consequences of such an excessive unnecessary fire.

The Forest Service allocated a small amount of funding to rebuild burned allotment fences. But it was a joke. They hired a contractor who did a poor job, then their contracting officer inspected and approved this job. Neither party understood how to build fence that would last for several years in rugged country with heavy snowfall.

Of course the Forest Service wouldn’t listen to the knowledgeable permit holder because he’s “not qualified.” It’s no longer the Forest Service’s concern - job completed, contractor paid. Due to years of overspending, the Forest Service is now out of funding to provide maintenance materials to assist the permit holders. The permit holder is left with a worse fence than he had before this fire, yet still he is blamed when his cows are found “out of bounds.”

The permit holder is continually told to work together and “collaborate” with the different agencies trying to put him out of business, knowing full well the next time around there will be a new person “in charge” to deal with. Having kept all this together for generations by hard work and knowledge learned from trial and error, this long-time permit holder starts to ponder if his neighbors who sold out to subdividing might not be better off?

My family lost cattle in the Poe Cabin fire, suffering a monumental monetary loss. Personally I lost more.

I chose to resign after 15 years from my job with the U.S. Forest Service, something I had taken on to supplement our ranch income. The conflict between ranching and drawing a government paycheck had become too large. I harbor bitter feelings against past co-workers who I mistakenly thought respected my position.

Some say it took guts to step down, others call it stupid to have left a good-paying job in tough economic times. It’s neither. It’s called principle!

Shelley Neal is a fourth-generation rancher from Lucile, Idaho.

by Forrest Grump

by bear bait

Flight/fight in animals is a description of behavior. In humans, we call it paranoia. The people who are ready to run or fight are demeaned and called names, their integrity doubted.

Our government is no longer there to help us. It is there for its own sake. Look at today’s paper, and the percentage list of jobs lost by industry. The bright spot? 3% more people working for government. No matter how much Cheez Whiz you spread on the hula hoop, by the time it gets past government it is all gone, and you are without. Get used to it. It is the way things are, and will be, because the electorate prefers it that way.

Wow, that’s a real bummer. But yeah, principle is important.

Is there such a thing as malign neglect?