Climate and Weather Federal forest policy Forestry education Saving Forests

by admin

Is There a Forest Fire-Climate Connection?

by Mike Dubrasich

The Web is all atwitter with the latest news about an alleged global warming - forest fire relationship. The buzz was instigated by a new research paper published in the June issue of Ecological Applications.

The paper is Climate and wildfire area burned in western U.S. ecoprovinces, 1916–2003 by Jeremy S. Littell, Donald Mckenzie, David L. Peterson, and Anthony L. Westerling. The full text is [here]*, generously provided to us by the lead author**.

*The original link to the full text was withdrawn following threats made by Ecological Applications. For more discussion regarding that worm can, see [here].

** A new “legal” link to the full paper [here] has been supplied by the lead author, Jeremy S. Littell of the Univ. of Washington. Thank you, Dr. Littell.

The USFS PNW Research Station (where co-author David L. Peterson works) posted a News Release about the paper [here].

In the warming West, climate most significant factor in fanning wildfire flames

Study finds that climate influence on production, drying of fuels-not higher temperatures or longer fire seasons alone-critical determinant of Western wildfire burned area

PORTLAND, Ore. June 26, 2009. The recent increase in area burned by wildfires in the Western United States is a product not of higher temperatures or longer fire seasons alone, but a complex relationship between climate and fuels that varies among different ecosystems, according to a study conducted by U.S. Forest Service and university scientists. The study is the most detailed examination of wildfire in the United States to date and appears in the current issue of the journal Ecological Applications. …

“We found that what matters most in accounting for large wildfires in the Western United States is how climate influences the build up-or production-and drying of fuels,” said Jeremy Littell, a research scientist with the University of Washington’s Climate Impacts Group and lead investigator of the study. “Climate affects fuels in different ecosystems differently, meaning that future wildfire size and, likely, severity depends on interactions between climate and fuel availability and production.” …

Note the careful use of the word “climate.” And note the disclaimer: global warming is NOT implicated. The News Release and the paper itself do not blame global warming (aka “higher temperatures”) for forest fires.

Instead, the researchers found that a combination of weather factors, including precipitation in the years immediately prior to the fires, may be partially correlated with fire acreage.

Note my use of the term “weather”. Average precipitation has not changed. Some years are dry, some are wet. Note also my use of the term “correlation.” Correlation is NOT causation. Note also my use of the term “partial.” The correlations found by the researchers were weak.

However, that did not stop the USFS PNW Research Station from leaping to conclusions that are at odds with what was carefully parsed in the paper:

Findings from the study suggest that, as the climate continues to warm, more area can be expected to burn, at least in northern portions of the West, corroborating what researchers have projected in previous studies. In addition, cooler, wetter areas that are relatively fire-free today, such as the west side of the Cascade Range, may be more prone to fire by mid-century if climate projections hold and weather becomes more extreme.

Note that the USFS PNW Research Station uses the word “warming” in their headline and in the paragraph quoted above, despite the fact that “warming” was not even studied or correlated, much less causational.

Note that the conclusions of the USFS PNW Research Station rely on “climate projections” that have nothing to do with the paper and are themselves unskillful and largely failures at predicting anything.

So what did the researchers actually find, and how skillful were they at their historical analysis (note again that they attempted no “projections” or “predictions” as those words are generally interpreted)?

The methods used began with documented historical data on wildfire acreage from 1916 to 2003 for the western US (from the Mississippi to the Pacific Ocean, excluding Alaska). That data was obtained from the USFS and was limited to federally protected lands in 11 states. The researchers acknowledge that the data had “systematic bias and uncertainty.”

They also obtained weather data (which they called “climate data”) for the same period from the National Climatic Data Center. The data included monthly state climate division precipitation (PPT), temperature (T), and Palmer drought severity index (PDSI) data. They did not obtain any snowpack data, although such exists.

The researchers then divided the ll state area into 16 “ecoprovinces” and used an algorithm (computer model) to attribute the fire acreage and weather data into each “ecoprovince.” More “systematic bias and uncertainty.”

Then they did a principal component analysis (PCA). This is a little bit difficult to explain in layman terms, but I’ll give it a shot.

PCA involves building regression models. First the outcome (response variable) is specified. In this case the response variable was the acreage burned each year.

Then the explanatory variables (the weather data) were combined into linear vectors, and a statistical treatment was done to find the “best” vectors (those that “explain” the response variable).

PCA has a logical fallacy built into it. The modelers assumed that the selected explanatory variables (PPT, T, and PDSI) are correlated with the response variable (fire acreage). Other potential explanatory variables (such as fuel loading, fire suppression capability, firefighting policies, wind, beetle infestations, human responses, human error, etc.) were not considered. Then the PCA method chose the combination of the selected explanatory variables that had the highest correlation to the response variable.

Some refer to that as “data mining,” but it ought to be called “data polishing.” In essence, PCA finds what the users want to find. It does not yield unbiased, comprehensive analyses.

Out of a hundred likely explanatory variables, three were chosen by the modelers. Then those were forced into the model and tweaked until the best fit was found. If other explanatory variables had been included, there is a strong possibility that the three that were chosen would not have been significant at all. The correlations of the other (not selected) explanatory variables might have (probably would have) drowned out any of the correlations of the chosen three.

And the tweaking for best fit gives undue (lacking in theoretical basis) weights to this or that variable. In addition, the non-Bayesian frequentist approach used by the researchers significantly underestimates the true variance (uncertainty).

And as I said, correlation is NOT causation. The price of tea in China or the first thousand phone numbers in the phone book might have had just as much correlation with the response variable as the chosen explanatory variables. That does not mean they (tea prices, phone numbers, weather data points) caused any differences in fire acreage.

For instance, in some of the “ecoprovinces” the spring precipitation was positively correlated with fire acreage, and in others it was negatively correlated (see Tables 3 and 4 in the paper), and the weights given to that variable (or to any of the variables in any of the models) were not reported at all. So was high or low spring precipitation causational? If so, which one?

Every “ecoprovince” ended up with a different model. In some models the winter weather gave the best fit, and in some the spring weather was more highly correlated. But causation cannot be logically inferred from correlation. That’s a Rule of Science.

To be fair to the authors/researchers, they noted these “discrepancies” and hypothesized why they might be.

Dry, warm conditions in the seasons leading up to and including the fire season are associated with increased WFAB [wildfire area burned] in most ecoprovinces (Appendices A and B; Table 2), particularly in the northern and mountain ecoprovinces (Fig. 2). The mechanism for the relationship is, presumably, that low precipitation and high evapotranspiration deplete fuel moisture over larger than normal areas (Keetch and Byram 1968, Bessie and Johnson 1995). These conditions increase the probability of ignition (fine, dead fuels) as well as the potential for fire spread (dead fuels of all sizes, usually 1-100 hr fuels such as canopy and shrub foliage or grasses; Van Wagner 1977). Lack of precipitation in the year of fire is more important than drought (PDSI) or temperature in most regressions, although PDSI is a better predictor in some ecoprovinces, especially the northern and middle Rocky Mountain ecoprovinces.

In contrast, in the southwestern and arid ecoprovinces, moist conditions the seasons prior to the fire season are more important than warmer temperatures or drought conditions in the year of fire. Moist conditions produce fine fuels in the understory, which cure in subsequent years to become available fuels, prior to the arrival of monsoon rain in the summer (Swetnam and Betancourt 1998).

There are other factors at play, though. The three explanatory variables chosen don’t even give a full picture of the weather (excuse me, “climate”).

Weather and climate are two different things, evidently. There’s a lot of folderol about that in the Blogosphere in recent years. If the weather is frightful, as it was for much of the country last winter, then that’s just anecdotal “weather.” But if we get a warm spell (as we did in Oregon in May) then that’s “climate change.” It all depends on whose ox is being gored. (There’s a pun in that last sentence; see if you can find it).

The authors/researchers note that “we did not examine snowpack explicitly.” Well, I did [here], for the Snake River watershed (which covers most of Idaho and parts of Nevada and Oregon). I found no trend (up or down) over the period from 1919 to 2007.

It is safe to assume that a 80+ year period reflects climate, and there was no change. Fancy that.

Moreover, wildfires and wildfire acreage are (obviously) associated with weather. Lightning ignites most wildfires, and when strong winds blow during fire season, small fires can explode into large ones. The large fires in Southern California and Idaho are almost always driven by gale-force winds (Santa Ana winds in the former case, Palouse winds in the latter). The same is true on the Rocky Mountain Front.

Those winds are perennial. They are part of the climate in those places. But their specific occurrences at particular dates are weather.

Other factors that affect fire acreage also include Federal fire policy. Recent megafires such as the Biscuit Fire, Warm Fire, Zaca Fire, Indians/Basin Fire, South Barker Fire, and many others were the direct result of choices made by fire managers to Let It Burn. The policy decisions have various monikers, such as Wildland Fire Use (whoofoo), Appropriate Management Response (hammer), Fires Used For Resource Benefit (foofurb), Prescribed Natural Fire (PNF), etc., but they amount to the same thing: fire acreage determined by fire management policy, not weather and certainly not climate.

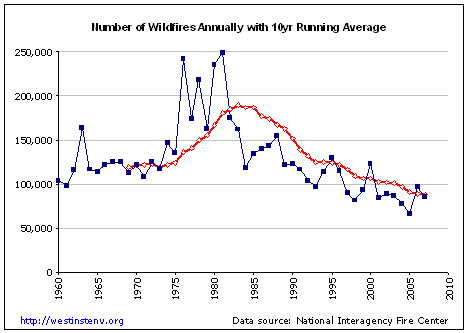

Shifting fire policy is nothing new, either. In 1935 the USFS under Chief Forester Gus Silcox instituted the 10-AM Policy, which mandated that fires be contained by 10-AM the day following detection. CCC crews were available to implement it. Fire acreage declined, even though the Dust Bowl years are generally acknowledged as some of the warmest on record.

During World War II fire acreage went up, principally because the fire crews were overseas fighting a war. That was during a period of declining temperatures. After WWII smokejumping became a much used firefighting technique, and fire acreage declined again. In the 1970’s the 10-AM policy was discarded, and fire acreage rose again. The Yellowstone fires in 1988 were an outgrowth of the adoption of PNF.

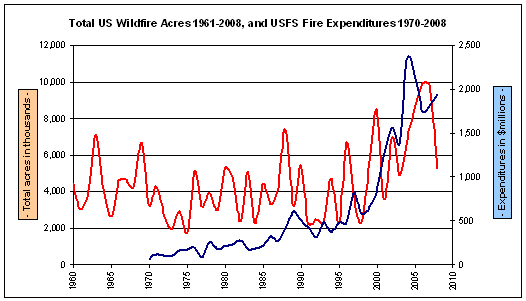

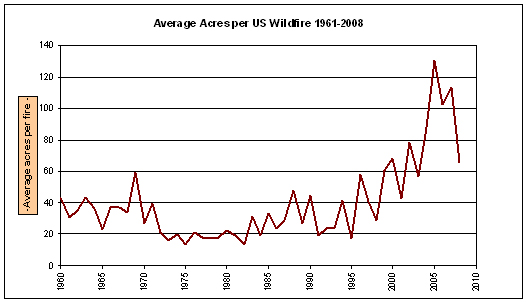

Bill Clinton’s USFS Chief Mike Dombeck made fundamental changes to fire policy and to management policy, in effect abandoning active management. Total fire acreage and average acres per fire have been increasing ever since, despite exponentially increasing firefighting expenditures.

The authors/researchers note:

It is possible, for example, that other factors, not just suppression, led to the recently observed increase in area burned (Stephens 2005). Among these factors, climate appears to be an important driver of fire area (Stephens 2005) and frequency (Westerling et al. 2006).

Yet fire frequency has fallen.

If a warming climate has increased fire frequency as claimed, then why have the number of fires declined steadily since 1980? Has there been cooling? (Indeed, there has been since 1998). Or is the conjectured connection between climate and fire frequency a faulty one?

And of course, it’s the fuels that burn. No fuels, no fire. Excessive fuels, excessive fire.

The authors/researchers recognize some of these limitations to their study. Much of the hype associated with the paper fails to consider those limitations, but the authors/researchers did, to some extent. If they also fanned the flames of the hype, and I’m not saying they did or didn’t, that would detract from their scientific dispassion and would reflect badly on them. But I’m not making that accusation.

They did conclude that “fuels management” may not be sufficient to reduce fire acreage:

Recognizing that most ecoprovinces have significant ecological variability, climate-limited ecoprovinces may be less influenced by fuel treatment than fuel-limited ecoprovinces (at least for area burned, if not fire severity). This argument also implies that management options for responding to climate change might be more or less limited, depending on the nature of fire climate relationships. In fuel-limited ecosystems, fuel treatments can probably mitigate fire vulnerability and increase resilience more readily than in climate-limited ecosystems in which adaptation to climate change is a more realistic approach.

There are weasel words in that passage, and a kind of fatalism about “climate change” that is not warranted, in my opinion. But I do agree that “fuels management” is not sufficient in and of itself to reduce fire acreage.

I would go farther and say that reducing fire acreage is not even a worthy goal. More important is to reduce fire severity, and that can be accomplished by restoration forestry. To impart fire resiliency (the author/researchers used that word) means restoring historical stand structures that withstood fires in past eras when the climate was (perhaps) a little different, and in any case the weather was as variable as it is today.

Restoration forestry also must include a more responsible and cooperative arrangement with fire management. As long as the fire community is divorced from the land management community, the propensity of the former to destroy the work of the latter will sabotage stewardship efforts.

There is no reason to abandon our forests to catastrophic immolation and conversion to fire-type brush, whether the climate is “changing” or not. There is every reason to prevent that outcome by responsible stewardship.

I absolutely part company with people who would destroy our priceless heritage forests in the name of social impotency and unskillful “projections” of climate change. If “adaptation to climate change” means Let It Burn, then count me out.

We should, can, and indeed must take better care of our heritage forests, regardless of political (not scientific) apocalyptic paroxysms. Smugness in the face of our crisis of catastrophic forest fires is not acceptable.

by John M.

I would suggest the measurement of fire damage/loss/destruction, or whatever, is not served well by simply measuring acres burned. Mike’s point about severity needs more discussion, and there is a need to better measure what are the negatives of the fire. For example, a range fire can lead to significant spread of non native plants such as “Cheat Grass” resulting in more native, less aggressive, plants being forced out. On the other hand, depending on timing and fire severity, native plants could benefit. The same holds true in other plant communities such as forests. And in all plant communities the changes in vegetation and soils caused by fire will have winners and losers for plants, animals,insects and humans.

Fire is a complicated force that needs to be looked at in wider view in my opinion, a view that includes, biology, economics, social impacts and long term natural resource needs. Wildfire is more than acres burned and structures lost, and needs to be thought about in the larger context of its short and long term influence on human and natural resource well being.

I wish it was possible to get people to look at this bigger picture rather than attempting to tie such discussions to the latest “The sky is falling!” media fad.

by NED

The Forest Service is attempting to relate large fires to global warming for political reasons.

Any graduate of Basic Fire Behavior should know that factors affecting fire behavior are climate, weather, topography, and fuel. I would also add suppression (the decision to take aggressive action or a decision to let the fire burn) as an important factor.

By blaming global warming or “climate change” the agency is attempting to place the reason for large fires on climate and not on the failure to manage fuels and the policy to let fires burn in the name of “wildland fire use” and “appropriate management response”. If global warming is fact, (I don’t believe it is), then fuels management, including a sensible fire management policy becomes even more important.

Excessive fuels mean more intense fire. We are starting to see reburns in fire related excessive fuels. We will see more of it in the future. I strongly agree that it is more important to reduce fire severity through restoration forestry than to worry about fire size.

The end to logging on public lands, which might be graphed in terms of millions of board feet logged (not sold but logged) per year on lands public and private, imposed over the acres burned would be an interesting comparison. Most likely that will never come from Federal researchers, because they are firmly controlled by the NGOs of no logging.

Or, the graph as a function of showing burns by large block Federal or Private, and then co-mingled or checkerboard lands private and public, and finally all fires on all acres, public and pirvate. And do this not just for the West, or the “fire prone” areas of the U.S., as they all are fire prone at some time in their fuel buildup. The South, MidWest, New England, the Rocky Mtn regions, and the West…

The most glaring of omissions is the inclusion of “fire for resource benefit” or “wfu” fire. That certainly shows up on graphs as more fire now than yesterday or yesteryear. It would seem you can’t purposefully burn, ignite, or allow ignition and fire to run its course, and then make any statements about global climate change, fire weather patterns, or any other comparison with prior decades of land management and fire protection as well as fire suppression. Apples and oranges deal.

I guess, and this is just my guess, that complex civil service systems served by a corrupt elected elite who take thousands from special interests to direct the spending of trillions, skews any attempt at common sensical approaches to tending the wild. Pogo had it right. So we will see more fire, less attempts at limiting resource damage, all excused by global climate change. I do wonder if that will become the defense of choice for all criminal activity. “I couldn’t help myself. I was driven to do it by global climate change to survive.” As algore drives his V-12 Mercedes up the paved driveway to his little Versailles palace in Tennessee, hundred dollar bills falling from his every pocket and bag. “Follow the money” is to follow the growth of global climate change and the need to create a new Ponzi for the Wall Street financiers. ca-ching!!